It is almost “like a bride’s outfit”; in it, there’s “something old, something new, something borrowed”—although rarely anything “blue.” That is how media critic Gilbert Seldes described the language of broadcasters, the jargon used by those behind the scenes of television, with which the American public was just getting acquainted (rather than walking down the aisle). Seldes’s remark can be found in Radio Alphabet (1946), a lexicon more concerned, at the title implies, with a poor relation of television. Let us say, a wealthy and powerful relation that was about to be abandoned by her suitors and cheated out of her fortunes.

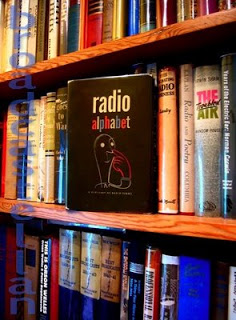

Despite its inclusion of TV terminology, the Alphabet was compiled at a time when radio was at the height of its influence on American culture, shortly before it was reduced to playing the nation’s jukebox and serving as a source of patter. It not only spouted words—it begot them. Hence the publication of Radio Alphabet, the latest addition to my library of books on broadcasting (also available online). Before it, along with everything else, is being shoved into a box, awaiting a new home, I am going to pick it up and . . . have a word.

Radio Alphabet is prefaced by “an introductory program”—a foreword as broadcast script featuring the voices of many important figures in charge of operations at the Columbia Broadcasting System. Among them, Douglas Coulter, vice-president of the network; William B. Lodge, director of general engineering; William C. Gittinger, vice-president in charge of sales; William C. Ackerman, director of the network’s reference department; Elmo C. Wilson, director of the research department; Howard A. Chinn, chief audio engineer for CBS; and radio drama director Earle McGill. All of them are announced and quizzed by a “Voice”—a sort of mouthpiece for broadcasting (or CBS, at any rate).

Like any good announcer, the “Voice” knows how to sell:

Not since Gutenberg’s press has any instrument devised by man added more promise to the dimensions of man’s mind, or more altered the shape of his thinking. The press enabled man to speak his mind to man through a code of letters on paper: radio enables man to speak his mind by living voice. This expansion, under the somewhat imperative tempo of the radio art, has forced up a new, raw, essential working vocabulary which is steadily spilling over into wider understanding and usage.

Radio’s new operating tongue speaks now and then with fresh if familiar economy and color. In the air a pilot on the beam is on his course; on the air an actor or director or conductor on the beam is making his most effective use of the microphone. Bite off, bend the needle, west of Denver, soap opera, dead air, old sexton . . . these are new and useful and happy twists of the infinitely flexible mother tongue.

By now, the items in the Alphabet are largely useless; the unhappy twist is that radio’s tongue is tied, its jargon obsolete. However vivid the expressions in this glossary, consulting it makes you aware not only of the life of the medium but of the mortality of words. Although many of them linger in our vocabulary, they are figures of speech whose meanings have become arcane, whose uses are imprecise. These days, for instance, “soap opera” denotes melodrama, regardless of its financing or commercial purposes. It’s an expression on life support, a ghost of a word removed from the machine that created it.

Turning the pages of this handsome little volume is not unlike tuning in to those old programs and putting one’s impressions about them into words. There is that sense of being superannuated and abstruse; but there is also the thrill of rediscovery and the joy of being, in a word, conversant—at least with the subject.

So, what does it mean to have been in a “cornfield,” “west of Denver,” “calling hogs”? I’ll let the Radio Alphabet explain it all:

CORNFIELD: A studio setup employing a number of standing microphones.

WEST OF DENVER: Technical troubles which can’t be located.

HOG CALLING CONTEST: A strenuous commercial audition for announcers possessed of pear-shaped tones of voice.