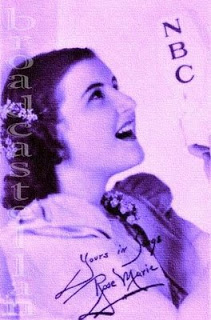

I couldn’t believe my eyes. I couldn’t believe my ears, either. That is how I felt when I first watched International House (1933) and saw the sensational Baby Rose Marie belting out “My Bluebird Is Singing the Blues.” Watch out, Shirley Temple, I thought, this kid has got a little more octane; she’s more Maker’s Mark than Little Miss Marker, more moonshine than Sunnybrook. Today, that kid is celebrating her ( )th birthday. Her shoes may be on display at the Smithsonian in a few weeks; but, later this year, she is also going to be back on the screen—in a movie adaptation of the musical revue Forever Plaid. To find out more about the wunderkind from her own lips, I am tuning in to the first installment of a five-part interview with Rose Marie, recorded in 1999.

I couldn’t believe my eyes. I couldn’t believe my ears, either. That is how I felt when I first watched International House (1933) and saw the sensational Baby Rose Marie belting out “My Bluebird Is Singing the Blues.” Watch out, Shirley Temple, I thought, this kid has got a little more octane; she’s more Maker’s Mark than Little Miss Marker, more moonshine than Sunnybrook. Today, that kid is celebrating her ( )th birthday. Her shoes may be on display at the Smithsonian in a few weeks; but, later this year, she is also going to be back on the screen—in a movie adaptation of the musical revue Forever Plaid. To find out more about the wunderkind from her own lips, I am tuning in to the first installment of a five-part interview with Rose Marie, recorded in 1999.

The interviewer, one Karen Herman, is about as dense as a pea souper, only far less absorbing; but the quondam phenom doesn’t seem to be phased by it, brushing aside or simply ignoring what she does not care to hear or answer: “Age is only good with wine and cheese,” she responds when Herman quizzes her on her date of birth, something “Baby” had to deal with right from the start of her career.

She also had to deal with doubters like me who, listening to her, imagined a rather more mature performer. “I never sounded like a child. I never had a Shirley Temple voice. Always had a Sophie Tucker type of voice,” Rose Marie commented. Now, that is a problem for a performer who is not seen. Sure enough, the singer-actress recalls, “people started writing in letters saying ‘that’s not a child, that’s a thirty-year-old midget.'” So, the alleged midget was sent on tour around the country.

Very little of Rose Marie’s many years on NBC radio is extant or readily available today. A clip from the 14 March 1938 broadcast of the Baby Rose Marie Show may be found here. Among the number is the catchy “How’dja Like to Love Me?” from College Swing (1938). Nearly a decade later, in 1947, “the little tyke who used to be in movies and on the air” was featured on Command Performance, hosted by a cheerfully daft Ken Niles, who was looking forward to holding her in his lap once again. Ginger Rogers set him right by describing Rose Marie to listeners as a “grown-up, luscious, attractive blonde.” “Well . . . ?” Niles replies rather salaciously and invites the guest to come up to his apartment to look at his rattles.

Mercifully cutting short the patter, Rose Marie sings “My Mama Says No, No” and, later in the program, goes back to the year 1926 BS (“before Sinatra) and does a swell Jimmy Durante impression (also heard on Durante’s own show).

This anniversary strikes me as just the occasion to reopen my Gallery of Radio Stars . . .

So, Carole Lombard and Clark Gable got married on this day, 29 March, back in 1939. Ginger Rogers tied the proverbial knot with someone or other in 1929; dear Molly Sugden, whom most folks today know as Mrs. Slocombe, a woman closest to her pussy, was Being Served, be it well or ill, with a license to wed in 1958; and the to me unspeakable ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair proved that he had popped the question fruitfully by walking down the aisle with someone named Cherie. It is a time-honored institution, no doubt; and one that has protected many a woman before her sex was granted the right to vote; but it is concept I find difficult to honor and impossible to obey nonetheless (which explains my love for the first three quarters of the average screwball comedy, the genre in which Lombard excelled).

So, Carole Lombard and Clark Gable got married on this day, 29 March, back in 1939. Ginger Rogers tied the proverbial knot with someone or other in 1929; dear Molly Sugden, whom most folks today know as Mrs. Slocombe, a woman closest to her pussy, was Being Served, be it well or ill, with a license to wed in 1958; and the to me unspeakable ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair proved that he had popped the question fruitfully by walking down the aisle with someone named Cherie. It is a time-honored institution, no doubt; and one that has protected many a woman before her sex was granted the right to vote; but it is concept I find difficult to honor and impossible to obey nonetheless (which explains my love for the first three quarters of the average screwball comedy, the genre in which Lombard excelled).