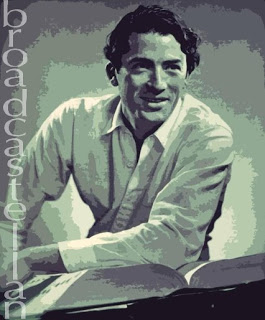

“The eternal providence has appointed me to watch over the life and death of all thy creatures. May I always see in the patient a fellow creature in pain. Grant me strength and opportunity always to extend the domain of my craft.” That is what was left of the Oath of Maimonides when it was uttered, on this day, 28 August, in 1945, on The Doctor Fights, a radio series dramatizing the challenges of physicians operating in the theater of war. Gregory Peck read those lines with a dignity becoming the profession; at the same time, he lifted The Doctor Fights above the dubious status of an infomercial for the pharmaceutical concern sponsoring the series.

“The eternal providence has appointed me to watch over the life and death of all thy creatures. May I always see in the patient a fellow creature in pain. Grant me strength and opportunity always to extend the domain of my craft.” That is what was left of the Oath of Maimonides when it was uttered, on this day, 28 August, in 1945, on The Doctor Fights, a radio series dramatizing the challenges of physicians operating in the theater of war. Gregory Peck read those lines with a dignity becoming the profession; at the same time, he lifted The Doctor Fights above the dubious status of an infomercial for the pharmaceutical concern sponsoring the series.

The program was fast losing its edge, now that World War II had officially come to an end. The Doctor was fighting his last ratings battles; but the fight for dominance of the world market was just getting under way. “With the rest of America,” the sponsor, Schenley Laboratories, was looking “with great expectation toward the limitless afforded by peace. Opportunities for bettering the lot of all mankind.”

As anyone knows who has watched The Third Man, war-devastated Europe was a crippled, corrupted, and cadaverous body aching for medical treatment; and announcer Jimmy Wallington spelled out where the opportunities lay for improvement and profit: “One of the greatest among these gifts of medicine is Penicillin. Born of war, this promising drug will contribute much toward making a peacetime world in which disease and suffering reach a new and all-time low.” No mention is made of the all-time lows in the field of advertising, which hit the airwaves for the first time on this day, 28 August, back in 1922.

The Oath of Maimonides, which may be of German origin, is uttered in many variations; but most of them argue the physician to have been appointed to “watch over the life and health” of the human race, not over its “life and death.” This is a peculiar phrasing, given the program’s sponsor. Should doctors merely stand by and “watch over” people’s death, or do their utmost to see to its prevention? Perhaps, the war had been turning the Oath into a curse, as doctors were called upon to heal those who were prepared and ruthless enough to cause them harm.

Such a story is the “Medicine for the Enemy,” the episode scheduled for 28 August 1945. Purportedly, it is the “true story of Lieutenant Commander Harry Joseph,” whom Peck portrays and who is interviewed at the close of the program. As a medical officer aboard the destroyer USS Osmond Ingram, Joseph is low on penicillin, but faced with the duty of having to care for the thirteen Germans who survived the sinking of their submarine.

“What if one of our own men’s injured before we get back to port,” the doctor confides in the captain, “and the only medicine that can save him has been used up on enemy prisoners?” He is reminded that it is “up to [him]” to make such decisions. Clearly, the Oath has been revised for such occasions of watching “over the life and death” of “creatures” foreign and hostile.

Foreign and hostile they are, those Nazi prisoners, men who would rather die than be treated by a non-Aryan. “The first time since I’ve been a doctor,” Joseph tells the German commander, a man twice blinded, by hatred and acid, “I’m not sure I care.”

The medical officer realizes that, in order to heal the body, he has to fight as well the ignorance and arrogance of the proud Nazis, applying “doses of truth, backed up by facts. That was the treatment used in combating the disease.” In dispensing this “anti-toxin for fascism” along with the Penicillin administered on behalf of the sponsor, Peck that was doing so, the actor who portrayed Joseph was preparing for the roles for which he became famous.

Well, call me . . . whatever you like, but I am prickly when it comes to the protection of endangered species; those of the literary kind, I mean. Take Moby-Dick, for instance. Go ahead, so many have taken it before you, ripped out its guts and turned it into some cautionary tale warning against blind ambition and nature-defying obsession. Moral lessons are like sardines: readily tinned and easily stored until dispensed; but they become offensive when examined closely and exposed for much longer than it takes to swallow them.

Well, call me . . . whatever you like, but I am prickly when it comes to the protection of endangered species; those of the literary kind, I mean. Take Moby-Dick, for instance. Go ahead, so many have taken it before you, ripped out its guts and turned it into some cautionary tale warning against blind ambition and nature-defying obsession. Moral lessons are like sardines: readily tinned and easily stored until dispensed; but they become offensive when examined closely and exposed for much longer than it takes to swallow them.