As my motto ‘Keeping up with the out-of-date’ is meant to suggest, I tend to look toward the past; and yet, I resist retreat. Retrospection is not retrogressive; nor need it be it a way of reverencing what is presumably lost or of gaining belated control over what back at a certain time of ‘then’ was the uncertainty of life in progress. I am interested in finding the ‘now’ – my ‘now’ – in the ‘then,’ or vice versa, and in wresting currency from recurrences.

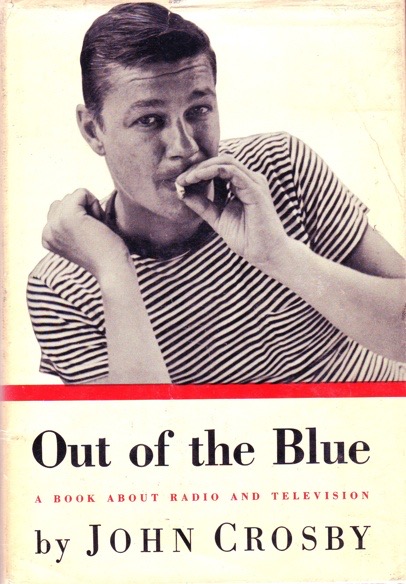

I also tend to look at the ephemeral and everyday, the disposable objects or throwaway remarks we think or rather do not think of at all and dismiss as immaterial and obsolete, as too flimsy to carry any weight for any length of time. Take an old syndicated newspaper column such as John Crosby’s “Radio in Review,” for instance. Back in November 1948, Crosby, whose writing was generally concerned with programs and personalities then on the air, commented on a US presidential election that apparently no one, at least no one in the news media, had predicted accurately. “Dewey Defeats Truman,” the headline of the Chicago Daily Tribune erroneously read on 3 November that year. Having listened to the words dispensed over the airwave on that day after – or, depending on your politics, in the aftermath of an election that paved the way for another term for President Harry S. Truman – Crosby noted:

‘Perhaps never before have such handsome admissions of error reverb[e]rated from so many lips with such a degree of humility as they did on the air last week.’ Truman had been in office since the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945; but in 1948, he had confirmation at last that the public – or the majority of those who made their views public and official – agreed that he belonged there. As Crosby pointed out, even seasoned political commentators had predicted a Republican victory.

‘[T]here probably never has been an election post-mortem in which the words “I told you so” were not heard at all,’ the columnist remarked, adding that ‘if they were said, [he] didn’t hear them.’ To his knowledge, ‘[n]o professional commentators … told anyone so.’

Among those who, according to Crosby, got it more wrong than others was the ultra-conservative broadcaster Fulton Lewis Jr., an opportunist and influencer who, Crosby remarked, had gone ‘far beyond’ his fellow commentators by predicting ‘Republican victories in states where most observers foresaw a seesaw battle.’

Speaking from the secular pulpit that was his radio program, Lewis ‘fully admitted his wrongness’ after the fact, Crosby noted, reading aloud the messages he received from listeners who ‘invited him to drop dead,’ to ‘throw himself’ into Chesapeake Bay, or to ‘go soak his head in a vinegar barrel.’ Far from remorseful or self-deprecating, such revelling in controversy is representative of right-wing provocation as we experience it to this day.

A question not posed by Crosby is whether future Barry Goldwater supporter Lewis simply got it wrong – or whether he predicted wrongly to demoralise Truman’s supporters by suggesting that a Republican landslide was a foregone conclusion. Given Lewis’s known bias, the miscalculation was obviously not calculated to rattle Truman supporters out of complacency. So, a question worth asking now not how commentators got it so wrong, but why.

Lowell Thomas, a conservative commentator courting an audience of both major parties, insisted that he had not predicted the election but that he had merely ‘passed along the opinions of others.’ Thomas added, however, that, had he made a prediction, ‘he’d have been as wrong as everyone else.’ Unlike Lewis, this statement suggests, Thomas distinguished between reportage and commentary, the line between which was drawn no more clearly in 1948 broadcasting than it is in today’s mass media, discredited though they are as ‘legacy’ and presumably obsolete by the social media weaponizing political right.

Reporter Elmer Davis who, also unlike Lewis, was critical of then on-the-rise Senator Joseph McCarthy, a Democrat who turned Republican and opposed the Truman presidency for being soft on Communism, provided this statement to his listeners: ‘Any of us,’ he said, ‘who analyze news on the radio or in the papers must hesitate to try to offer any explanation to a public which remembers too well the lucid and convicing explanations we all offered day before yesterday of why Dewey had it in the bag.’ Commentators had ‘beaten’ their ‘breasts’ and ‘heaped ashes’ on their heads since the election, Davis told his audience; but they still looked ‘pretty foolish’ and should probably wait some time before sticking their ‘necks’ out again.

‘Cheer up, you losers,’ veteran newscaster H. V. Kaltenborn declared on his radio program, ‘It isn’t so bad as you think.’ The peculiar mash-up of scoffing, commiserating, mind-reading and prognosticating did not escape Crosby, who wondered just what went on in the ‘mind’ of someone who, more than having misjudged who lost, might himself have lost it.

The ‘explanations as to why President Truman won were almost as identical as the pre-election prediction that he wouldn’t,’ Crosby observed, namely that the nation ‘liked an underdog.’ Just how much of an ‘underdog’ can a presidential incumbent be? Playing one on TV would prove a winning formula for Donald Trump, at least, and the kind of doghouse he managed to furnish for himself, which is so unlike the residence some of us envision as rightfully his, provides support of that theory.

Summing up the state of desperation among commentators, Crosby stated that ‘many’ of them derived rather ‘odd comfort’ from the fact that US ally turned adversary Josef Stalin, who likewise incorrectly predicted a win for Republican candidate Thomas E. Dewey, ‘had been just as wrong as they were.’

Sure, there is momentary relief in Schadenfreude, seeing those who got it wrong having to admit – or trying to avoid admitting – the fact that, in hindsight, they were demonstrably wrong, and, being wrong, on the wrong side of the future. And yet, getting it wrong may also be evidence of wrongdoing, of deceit and deviousness. As someone relegated to the sidelines, I can offer only one reasonable piece of advice to those who prefer a Truman over a Trump: pay attention to but do not trust folks who are determined to convince you that your vote does not matter much by declaring the game to be over when it is still afoot.