The themed window of our local Oxfam bookshop here in Aberystwyth was something to behold on that bright July afternoon. A row of handsome, second-hand but well-preserved copies of once popular fiction beckoned, reminding me of the tag I had chosen for this blog devoted to unpopular culture upon its inception back in 2005: “Keeping up with the out-of-date.”

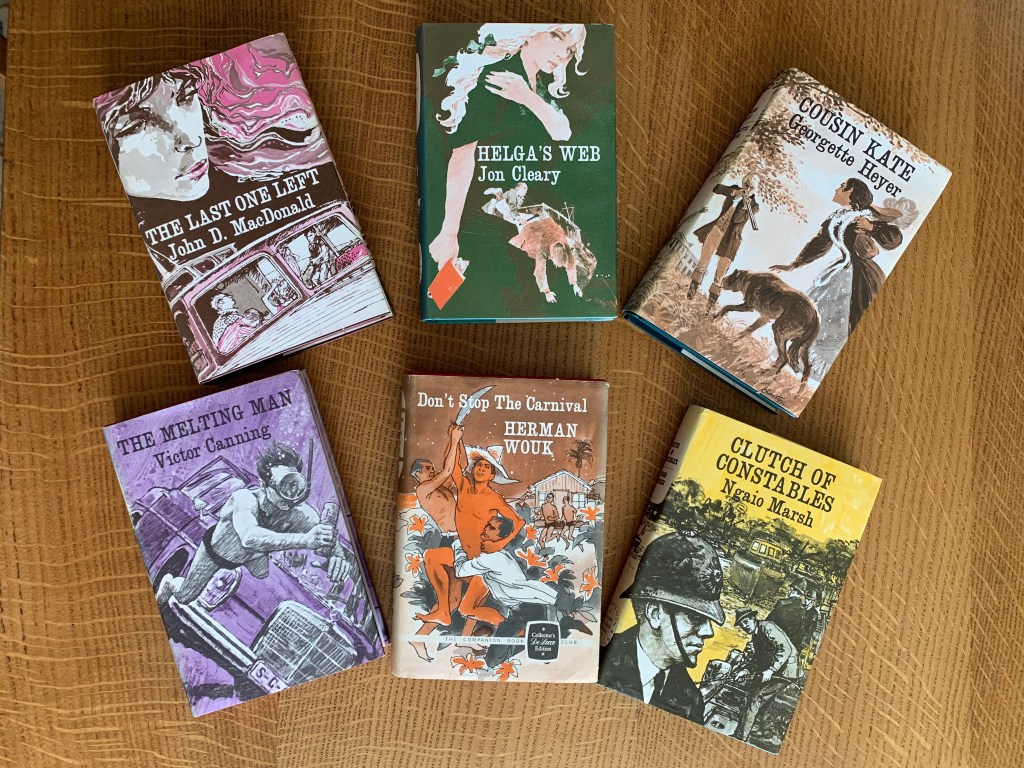

A novelist friend and avid reader, who had come from London for a visit, treated me to a volume of my choice. Three of them, in fact, as the £5-for-three deal made it unnecessary to be quite so discriminating. I passed up on erstwhile bestsellers by A. J. Cronin and Pearl S. Buck, both of whom had vanished from the display a day later, when I returned for another three titles (all six are pictured above). My first choice, however, had been Herman Wouk’s Don’t Stop the Carnival (1965).

I remember picking up Wouk’s tome Youngblood Hawke (1962), in a German translation, from my parent’s sparse bookshelves. My grandfather, likewise, was a Wouk reader, even though his chief interest lay in the writer’s Second World War subjects, to which Opa Heinrich, a former POW, could relate. In my late teens, desultory though my readings were, I enjoyed Wouk’s earlier City Boy (1948) and Marjorie Morningstar (1955).

My next encounter with Wouk’s writings dates from my years of graduate studies in New York. I had decided to ditch Thomas Carlyle as a subject and instead write a PhD study on US radio plays. Wouk, as I discussed here previously, had started as a radio writer or gagman. He satirized the industry in Aurora Dawn (1947) and reflected on his experience it in his autobiographical novel Inside, Outside (1985). From the latter I snatched the phrases “Hawkers of feces? Costermongers of shit?” – a reference to laxative commercials on the air – for the title of one of the chapters of Immaterial Culture to capture the dismissal of commercial radio as a legitimate literary forum by those who had written for broadcasting during the 1930s and 1940s but who gained prominence later as published writers and dramatists.

Long story short, I have a kind of casual relationship with Wouk as a writer, a relationship that at one point turned serious (or academic) due to my interest in radio. So, when I spotted that copy of Don’t Stop the Carnival, an old book new to me, I felt inclined to get reacquainted. It turned out to be a bad date.

Don’t Stop the Carnival is a story of middle age. The action, of which there is plenty, is mainly set on an imaginary island in the Caribbean, anno 1959. The novel relates the misadventures of a New Yorker – Norman Paperman – who falls in love with what strikes him as a tropical paradise and decides to take over a hotel, having had no prior experience either with the business or with life on a tropical island. Complications abound, some less comical than others.

Paperman is a Mr. Blandings of sorts, a familiar figure in American fiction. He’d rather lay an egg elsewhere than suffer his ‘disenchantment with Manhattan’ a day longer:

the climbing prices, the increasing crowds and dirt, the gloomy weather, the slow bad transportation, the growing hoodlumism, the political corruption, the mushrooming of office buildings that were rectilinear atrocities of glass, the hideous jams in the few good restaurants, the collapse of decent service even in the luxury hotels, the extortionist prices of tickets to hit shows and the staleness of those hits, and the unutterably narrow weary repetitiousness of the New York life in general, and above all the life of a minor parasite like a press agent.

Perhaps, as his name suggests, Norman is not to be looked at as man but as a page – scribbled on, rather than blank, over the course of nearly fifty years. He may feel like turning over a new leaf – but his life is already scripted in ink that is indelible. Don’t Stop the Carnival sets us up for its conservative moral: stick with what you know, stop kvetching, and don’t even think that the grass could be greener than in Central Park in May.

While it responds to the modernity of its day – to the threat of nuclear war and the growing doubt in the progress narrative of the 1950s – the novel nonetheless shelters in the makeshift of retrospection: it looks back at the end of the Eisenhower years from the vantage point of the violent end of the Kennedy presidency to reflect on the so-called modern liberalism of the early to mid-1960s.

Was this choice of dating the action meant to suggest the datedness of the views expressed by the characters? What were the attitudes of the author toward race relations, civil rights and liberalism? In other words, what comments on the turmoil of the 1960s did Wouk make – or avoid making – by transporting back the readers of his day and dropping them off on an island that, for all its remoteness is nonetheless US territory, and that is about to be developed and exploited for its exoticism and natural resources?

The titular carnival is both figurative and metaphoric – an extended topsy-turvydom (or chaos) in which black mix and mate with white, queer live along straight folks, and Jews like Wouk’s protagonist Norman Paperman mingle with Catholics, Protestants, agnostics, pagans and atheists. He encounters bad infrastructure, worse bureaucracy, and political corruption. This island ain’t that different from Manhattan – which argues getting away from his former life to be futile and pointless.

The Carnival is not only shown to be a dead end but a deadly one. In the final pages of the novel, two characters are killed in quick succession – one central to the narrative, the other – the decidedly other – being marginal. The central one is Norman’s island fling, Iris Tramm, whom he knew as a celebrated actress two decades earlier and is surprised or reencounter, washed up but still alluring, as one of the guests in the hotel he decides to buy.

The island carnival is exposed as a tropical fever that means either death or cure – a cure for an uncommon warmth of non-traditional bonds and realized desires. Paperman recovers, and his understanding wife takes him “home.” His lover, meanwhile, must first lose the companionship of her dog, and then, trashing Paperman’s car while trying to reunite with her wounded pet at a veterinarian’s, her life. Was this the only out Wouk could conceive for a white woman who was the mistress of a black official who dared not to marry her?

It is the treatment of the marginal character of Hassim and his swift, unceremonious and unlamented disposal that lays bare Wouk’s fear of change: the antique dealer Hassim, introduced as a “rotund bald man” with a “bottom swaying like a woman’s,” who openly flirts with young men. In fact, the island is awash with middle-class homosexuals of all ages. Even Paperman’s hotel is pre-owned by a gay couple. And although he must have come across some of them in his former job as a Broadway press agent, Paperman is uneasy in their presence when he and Iris, his illicit love, visit an establishment frequented by gays:

Norman found the proprietor amusing, and he was enjoying the songs of his youth. But the Casa Encantada made him uneasy. Men were flirting with each other all around him; some were cuddling like teen-agers in a movie balcony. The boy in the pink shirt, biting his nails and constantly looking around in a scared way, sat at a small table with one of the rich pederasts from Signal Mountain, a pipe-smoking gray-haired man in tailored olive shirt and shorts, with young tan features carved by plastic surgery, and false teeth. Norman was glad when the proprietor finished a run of Noel Coward songs and left the piano, so that he and Iris could politely get out of the place.

Hassim is shot dead by a policeman, despite posing no risk and committing no crimes. The killing, which occurs in Paperman’s hotel and bar, the Gull Reef, is described in few words and elicits less of a response than the stabbing of a dog a few pages before this incident near the close of the novel.

“As a matter of fact, […] I feel sorry for the poor bugger,” is the response to the death of Hassim by one character, “munching on his thick-piled hamburger” not long after the killing.

“I’ve known thousands of those guys, and there’s no harm in ninety-nine out of a hundred of them. It’s just a sickness and it’s their own business. Though gosh knows, when I was a kid working backstage, I sure got some surprises. Yes ma’am, it was dam near worth my life to bend over and tie my shoelace, I tell you.” He laughed salaciously. His once green face was burning to an odd bronze color like an American Indian’s, and he looked very relaxed and happy. “Actually, Henny [who is Paperman’s wife], I almost hate to say this, but I think this thing’s going to prove a break for the Club. I bet the nances stop coming to Gull Reef after this.”

Such views are unchallenged by the narrator and the main character, who decides to sell his business – to the man expressing those views, no less – and return to New York. “People thought that this [his death] was a bit hard on Hassim,” the narrator sums, “but that the cop after all had only been doing his duty, and that one queer the less in the world was no grievous loss.” Case closed. Business open as usual.

Clearly, queers like me were not considered by Wouk to be among his readers. Targets, yes, but not target audiences. Even the academic treatment of homosexuality – the suggestion that famous writers of the past, too, might have been homosexuals – is ridiculed in the novel, with one PhD student, the lover of Paperman’s teenage daughter, nearly drowning in the sea.

Wouk, who died shortly before his 104th birthday in May 2019, lived beyond the middle age of Don’t Stop the Carnival for more than half a century. I doubt that I shall make him a companion again on whatever is left of my journey.

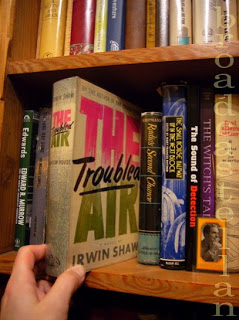

This being the birthday of novelist Irwin Shaw (1913-1984), I dusted off my copy of The Troubled Air (1951) to pay tribute to a radio writer who successfully channelled his anger and frustration by feeding it to the press, a rival medium that was only too pleased to get the dirt on broadcasting. Like his

This being the birthday of novelist Irwin Shaw (1913-1984), I dusted off my copy of The Troubled Air (1951) to pay tribute to a radio writer who successfully channelled his anger and frustration by feeding it to the press, a rival medium that was only too pleased to get the dirt on broadcasting. Like his

Meanwhile, no cross-promotion could save Arctic Manhunt (1949) from obscurity. Announced in the same issue of Radio and Television Mirror, it was meant to convince both the “man-hunting brunette” and the “girl whose man needs—a little encouragement” that lipstick was indispensable to the survival of the species. As yet, no five people of either sex could be found who saw and care to cast their vote for Arctic Manhunt on the Internet Movie Database. Whether or not the advertised product “lasts—and LASTS and L-A-S-T-S,” especially under the conditions endured in the forecast melodrama, I am in no position to say; but memories of those promised “pulse-quickening” scenes certainly faded fast. It takes more than corporate windbags to take them by storm.

Meanwhile, no cross-promotion could save Arctic Manhunt (1949) from obscurity. Announced in the same issue of Radio and Television Mirror, it was meant to convince both the “man-hunting brunette” and the “girl whose man needs—a little encouragement” that lipstick was indispensable to the survival of the species. As yet, no five people of either sex could be found who saw and care to cast their vote for Arctic Manhunt on the Internet Movie Database. Whether or not the advertised product “lasts—and LASTS and L-A-S-T-S,” especially under the conditions endured in the forecast melodrama, I am in no position to say; but memories of those promised “pulse-quickening” scenes certainly faded fast. It takes more than corporate windbags to take them by storm.