“Name your favorite radio star of 1950!” an article in Radio Guide for the week ending 18 April 1936 appealed to its readership (reputedly some 400,000 strong). It wasn’t a challenge to the clairvoyant or a call for votes in one of the magazine’s popularity polls, as the implied answer stared you right in the face, a promise with five sets of peepers. “The chances are you won’t be far wrong if your list includes Cecile Dionne, or Yvonne or Annette or Emile or Marie.” The famous Dionne Quintuplets, born on this day, 28 May, in 1934, were not yet two years old. No quintuplets before them had ever lived even that long; but their future in show business was already well mapped out for them, in contracts amounting to over half a million dollars. Opposite screen veteran Jean Hersholt—the quintessence of Hippocratic fidelity—those essential quints had already starred in The Country Doctor, released in March 1936, to be followed up by Reunion later that year.

Quite a life for carpetful of rug rats once described as “bluish-black in color, with bulging foreheads, small faces, wrinkled skin, soft and enlarged tummies, flaccid muscles and spider-like limbs!” However fortunate to escape life as a sideshow attraction, the medical history makers could “hardly avoid” being turned into celebrities and groomed for stardom.

“Whether they like it or not,” as the Radio Guide put it, “whether their guardians decree it, whether their parents give their permission, those five famous tots in Callander, Ontario, are the little princesses of the entire world. As such, they are already in and must remain in the public eye as long as the world demands them.”

Sure, the “public eye” tears up at the sight of babies, bouncing or otherwise—but the public ear? Would audiences tune in to hear a quintet of babbling, bawling infants? And what of all those other noises, the blue notes producers did not dare to mention, let alone set free into the FCC-conditioned air? Publications like Radio Guide paid fifty bucks for a single photograph of the famous handful (even though various if not always authentic pieces of memorabilia could be had considerably more cheaply), and that at a time when you could get your hands on the President’s likeness for a mere five; but would a sponsor risk investing thousands in an act that could not hold a tune or stick to a script? As yet, there was no evidence that the media darlings could blossom into a veritable Baby Rose Marie garden.

Defending Radio Guide’s continued attention to the Dionnes, editor Curtis Mitchell declared that, while the phenomenon “had little to do with radio,” “all the great personalities of every walk of life and every continent” eventually stepped up to the microphone: “As entertainers they may not have the expertness of Eddie Cantor or Jack Benny but their gurgling and cooing will surely remind us of what a magnificent instrument for participating in the life about us young Guglielmo Marconi provided when he invented radio.”

Sure enough, radio kept the multitudes abreast of the Dionnes while gag writers worked their name into many an old routine. Baby Snooks could stay snug, though. The infantas of Quintland would not baby talk themselves into the hearts of American radio listeners. According to legend (as perpetuated by Simon Callow), it was Orson Welles whom producers called upon to supply the “gurgling and cooing” when the babies were featured on a March of Time broadcast.

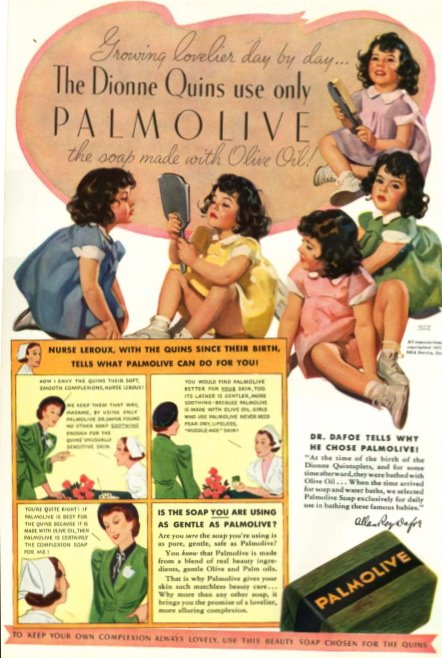

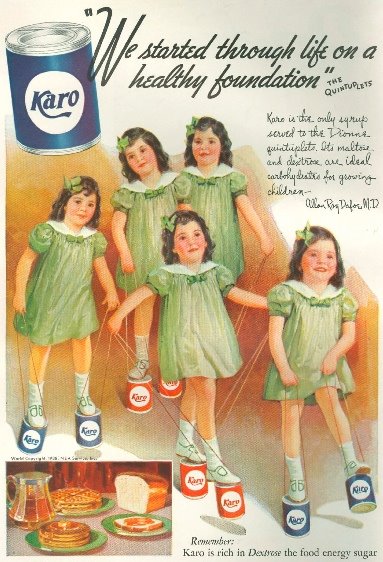

Accompanied by their physician, guardian and manager, Dr. Dafoe, the Dionne girls would be paraded before the listening public on several occasions in the early 1940s, and were even heard singing on the air; but they never became the ultimate sister act that readers of Radio Guide, anno 1936, had been encouraged to anticipate. Seen rather than heard, they nonetheless remained a prominent feature on the advertising pages of the Guide and other radio-related publications. All those endorsement deals and money-making schemes make you wonder what the Million Dollar Babies might have said if only they had been permitted to get a word in . . .

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. The Lady Astor Screen Guild Players have a surprise for you tonight.” Such a promise may well have sounded hollow to many of those tuning in to the

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. The Lady Astor Screen Guild Players have a surprise for you tonight.” Such a promise may well have sounded hollow to many of those tuning in to the