I have always been fortunate in having what is now conveniently termed a gaydar. Long before I knew what I could long for, long before I even dared longing, I simply knew or sensed what what was. What was what I was, that is. I looked into Raymond Burr’s eyes or listened to disco divas like Hazell Dean and, somehow, I could relate. Not to whatever their lines or notes were, not to the label that may nor may not become attached to their names, but to the individual behind or beneath, to the one who agreed to perform what was deemed suitable for mass reproduction. Ours was, is—and, I suppose, has to be—a society of re-producers, a society that accepts those who do not reproduce only as long as they churn out plenty of product and generate heaps of dough.

I have always been fortunate in having what is now conveniently termed a gaydar. Long before I knew what I could long for, long before I even dared longing, I simply knew or sensed what what was. What was what I was, that is. I looked into Raymond Burr’s eyes or listened to disco divas like Hazell Dean and, somehow, I could relate. Not to whatever their lines or notes were, not to the label that may nor may not become attached to their names, but to the individual behind or beneath, to the one who agreed to perform what was deemed suitable for mass reproduction. Ours was, is—and, I suppose, has to be—a society of re-producers, a society that accepts those who do not reproduce only as long as they churn out plenty of product and generate heaps of dough.

For all my queer gifts, which somewhat fail me here in Britain, where every other male seems somehow gay to me (gay, I say, not desirable), I never developed a sense of camp. I resent camp. To me, it is an act of wilful misreading, and that is empowerment at too great an expense—somebody else’s. You need to read the lines first before you can sneak between them, let alone get palimpsestic. After all, it is not that there has never been anything other to read, hear or see than the conventional, the traditional that then is mercilessly turned into—or, if you will, exposed as—travesty. There is always some code that permits you to identify—and identify with—a designated misfit or underdog, a guise for what you might feel yourself to be. Perhaps I am old-fashioned that way; but I do not insist on breaking something to pieces if it does not bend toward me.

I welcome melodramatic manipulation. I let it happen. It is an openness I bring to the popular arts, however cloaked in conventions and coded accordingly. How irritated was I when, during a screening of Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life at New York’s Public Theater, the audience started to snicker and swoon at the sight of Lana Turner’s admittedly fabulous sunglasses. I was absorbed in the to me already familiar action. I recall my father, a Hemingway-gone stoic who would rather die an alcoholic (which he did) than admit to being vulnerable, reduced to tears at the conclusion of the movie. And I respected him for that. If you cannot get drawn in at least once, just withdraw. I see no use in intellectual exercises removed from any felt engagement with the arts.

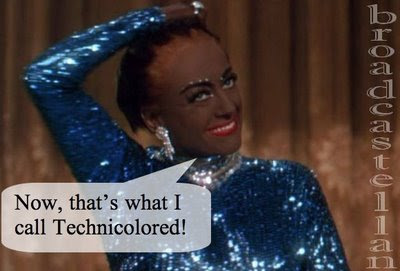

Sometimes, though, no involvement can be forced, no manipulation willed. You are being pushed or taken aback too far to venture an approach. Last night, for instance, I caught up with Torch Song (1953) and could only gape in disbelief at the misfireworks before me. I very nearly felt guilty watching the carnage as Joan Crawford goes into her blackface “Two-Faced Woman” routine as if this wreck of a vehicle were another Band Wagon. It is the self-destructive act of a perfectionist too delusional to notice the damage this would mean to what was left of her career.

However removed from any sense of reality, the story is remarkably close to the star’s own Hollywood history, reflective of her state and status then, of her demise as a leading lady which this film, in turn, accelerated. All the while, though, Crawford failed to elicit my compassion; her earnest and joyless quest for perfection turns Torch Song into a stilted, lifeless performance.

Torch Song is not quite Trog; but for all its glossy production values, it is monstrously inept. Crawford’s humorless performance is as uncomfortable to watch as the carefully choreographed moves of a dancer too focused on getting the steps right to notice the misstep of it all, too fixed on the floor to see where it is going.

Torch Song is, at best, a rehearsal—a rehearsal of a swan song recorded in the act of drowning. If only there had been room for a tongue in Crawford’s cheek, the dire melodrama leading up to the supposed triumph of “Two-Faced Woman” would not have been quite so jaw-droppingly awful. Even the film’s reflexivity does not improve matters, since the entire production is self-delusional rather than self-conscious. Torch Song is all about Crawford, not All About Eve. It may be concerned with the staging of a show and the dropping of masks; but even what is going on behind the scenes is all cardboard and paste.

It seems to me that Torch Song came about twenty years too late for Crawford. I don’t mean that she was too old for the part. Like Madonna, who turns fifty today, Crawford had an amazing figure on which rested the head of a business-hardened professional. To bowdlerize Sheridan, the trunk’s modern, ‘tho the head’s antique. No, it isn’t a question of Crawford’s fitness, but of the datedness of the material, a grab bag of hand-me-downs it would be generous to describe as contrived.

The only genuine article in the entire production is Marjorie Rambeau, who was both old and bold enough to play Crawford’s mother, imbuing her few moments on the screen with a wit and restrained sentimentality reminiscent of parts that often went to Thelma Ritter.

Today, Torch Song is considered classic camp, a status not reflected in the tepid reception from Internet Movie Database voters. Being among them, and having rated some 160-odd pictures so far, I am puzzled as to how to judge this unspectacular if spectacularly misjudged production. I am almost beginning to envy Michael Wilding’s character, a blind man to whom Crawford’s Gypsy Madonna appeared as the remembered image of her promising and glorious past; but then I keep thinking: Joan, as flattered as you might have been by the invitation to work once more at the studio that made you a star, you should not have taken those steps like a blissfully oblivious Norma Desmond. You were never away from Hollywood long enough not to know your place there. If only you had slipped and cracked a smile for all those people out there, in the dark, I would have been happy to carry the torch.

Fancy that, Florence Farley! You were one lucky teenager, when, early in March 1939, a photographer from the ever enterprising Hearst paper New York Journal American came to see a fashion show planned by you and the kids in your neighborhood—the none too fashionable Tenth Avenue in Manhattan. Subsequently, you were chosen to go to Hollywood and become a “Lady for a Day.” What’s more, on this day, 1 May, you got to tell millions of Americans about your experience, dutifully marvelling at the “simply swell” Lux toilet soap in return. After all, you were talking to Cecil B. DeMille, nominal producer of the Lux Radio Theater, and there had to be something in it for those who made you over, young lady, and made your day.

Fancy that, Florence Farley! You were one lucky teenager, when, early in March 1939, a photographer from the ever enterprising Hearst paper New York Journal American came to see a fashion show planned by you and the kids in your neighborhood—the none too fashionable Tenth Avenue in Manhattan. Subsequently, you were chosen to go to Hollywood and become a “Lady for a Day.” What’s more, on this day, 1 May, you got to tell millions of Americans about your experience, dutifully marvelling at the “simply swell” Lux toilet soap in return. After all, you were talking to Cecil B. DeMille, nominal producer of the Lux Radio Theater, and there had to be something in it for those who made you over, young lady, and made your day.

Well, they come to the remotest of spots, spreading their words—or the word—undaunted by the indifference or hostility with which they are greeted. Jehovah’s Witnesses, I mean. This morning, I’ve been listening for about an hour to two of these travelling preachers, one of whom likened our lack of receptiveness and knowledge to sitting in front of a broken television set. Actually, the two reminded me of radio announcers: hawkers with a mission who come into your home (or as near as you let them) to sell you ideas and convince you to tune in tomorrow—a tomorrow so protracted it might have been conceived by a soap opera writer if it weren’t quite so blissful.

Well, they come to the remotest of spots, spreading their words—or the word—undaunted by the indifference or hostility with which they are greeted. Jehovah’s Witnesses, I mean. This morning, I’ve been listening for about an hour to two of these travelling preachers, one of whom likened our lack of receptiveness and knowledge to sitting in front of a broken television set. Actually, the two reminded me of radio announcers: hawkers with a mission who come into your home (or as near as you let them) to sell you ideas and convince you to tune in tomorrow—a tomorrow so protracted it might have been conceived by a soap opera writer if it weren’t quite so blissful.

Last night, I watched The Damned Don’t Cry (1950), a seedy but glamorous rags-to-riches-to-rags melodrama starring Joan Crawford. Crawford was a perfectionist on screen, even though producers like Jerry Wald determined that, by the mid-1940s, her physiognomy was less than ideal and called for that extra layer of gauze in front of the lens to soften her mature looks (because most leading roles in Hollywood are, to this date, a little too young for anyone over forty). No doubt, Crawford’s need for control contributed to what those in the radio business called mike fright. When Crawford went on the air, starring in dramatic programs like Suspense, she insisted on being recorded for later broadcast rather than going on the air live. Apparently, to someone as protective of her persona as Crawford, any screw-up in radio insinuated something tantamount to crow’s feet on screen. Not to Crawford’s Johnny Guitar (1954) co-star and rival, though, the radio-trained and true Mercedes McCambridge.

Last night, I watched The Damned Don’t Cry (1950), a seedy but glamorous rags-to-riches-to-rags melodrama starring Joan Crawford. Crawford was a perfectionist on screen, even though producers like Jerry Wald determined that, by the mid-1940s, her physiognomy was less than ideal and called for that extra layer of gauze in front of the lens to soften her mature looks (because most leading roles in Hollywood are, to this date, a little too young for anyone over forty). No doubt, Crawford’s need for control contributed to what those in the radio business called mike fright. When Crawford went on the air, starring in dramatic programs like Suspense, she insisted on being recorded for later broadcast rather than going on the air live. Apparently, to someone as protective of her persona as Crawford, any screw-up in radio insinuated something tantamount to crow’s feet on screen. Not to Crawford’s Johnny Guitar (1954) co-star and rival, though, the radio-trained and true Mercedes McCambridge.