BBC Radio 3 is in the middle of a Milton season, designed to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the poet’s birth. This week, John Milton’s works are the subject of The Essay; his views, their significance and influence, are discussed on this week’s Sunday Feature, while excerpts from his poetry are recited on Words and Music. On 14 December, a new production of Milton’s Samson Agonistes will be presented by Drama on 3.

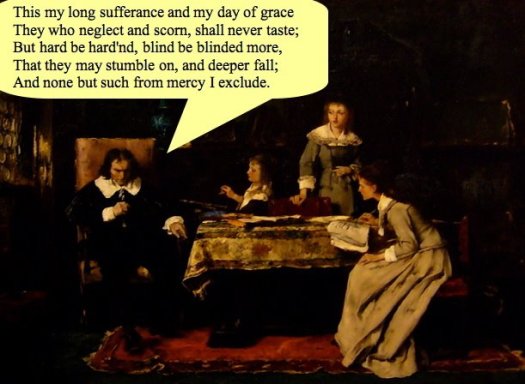

The wireless gave birth to the career of many a Milton, from announcers Milton Cross and John Milton Kennedy to comic Milton Berle. Among its writers numbers Milton Geiger, a playwright whom Best Broadcasts anthologist Max Wylie singled out for his ability to bring “reality and movement to a property that is in every sense an allegory.” More than any of those Miltons on the air, John, the poet and essayist, is truly in his element in the so-called blind medium of radio. His struggle to combat metaphorical blindness while being afflicted with physical sightlessness—a challenge that became the subject of a radio play (previously discussed here) was frequently the theme of his poetry, from “To Mr. Cyriack Skinner Upon His Blindness” to Paradise Lost and, finally, Samson Agonistes:

“O loss of sight, of thee I most complain!” the captured Samson, blinded and bereft of his powers, laments:

Blind among enemies! O worse than chains,

Dungeon, or beggary, or decrepit age!

Light, the prime work of God, to me is extinct,

And all her various objects of delight

Annulled, which might in part my grief have eased.

Inferior to the vilest now become

Of man or worm, the vilest here excel me:

They creep, yet see; I, dark in light, exposed

To daily fraud, contempt, abuse and wrong,

Within doors, or without, still as a fool,

In power of others, never in my own—

Scarce half I seem to live, dead more than half.

As a political writer eager to get his word out, Milton might have embraced the swift spreading of ideas that wireless technology makes possible. He would have seen in broadcasting the dissemination of so much good mingled “almost inseparably” with so much evil, from which the good is “hardly to be discerned.” To him, though, discernment was not the result of a shutting out of anything potentially harmful or ostensibly bad, but of a taking in of it all and an informed judging of its qualities. He would have welcomed the chance to have his words reach the ears of the multitude in a single broadcast, and of hearing the voices of others in an open forum.

Yet was there ever such a forum on the air? As he did in his Areopagitica, Milton would have objected to the licensing and censorship that threaten and curtail the freedom of speech. Commercial broadcasting, he might have argued, is not unlike Samson, betrayed, imprisoned and abused: “in power of others, never in [its] own,” a “moving grave” awaiting death by television. Even when it was still capable of bringing down the house, radio, like Samson, went down in the process before ever entirely convincing anyone of the power and virtue of sightless vision.

So, if Samson is Radio, who is his Delilah? Would it be television, the sponsors, radio executives, or, perhaps, the Philistine public at large?