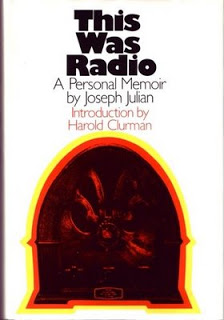

My grandmother refused to listen. She would walk out of the room whenever Marlene Dietrich appeared on the small screen. “She betrayed our country,” Oma would say, referring to Dietrich’s departure for Hollywood about the time the fascists came into power. Actually, Dietrich left a few years earlier; but the Nazis sure failed to lure her back. What a loss it is to turn a deaf ear to what aforementioned radio actor Joe Julian called “an exotic accent” and a “strong voice-presence.” Working with her in Dietrich’s lost radio series Café Istanbul (1952), Julian got a “glimpse behind the public image” and discovered

My grandmother refused to listen. She would walk out of the room whenever Marlene Dietrich appeared on the small screen. “She betrayed our country,” Oma would say, referring to Dietrich’s departure for Hollywood about the time the fascists came into power. Actually, Dietrich left a few years earlier; but the Nazis sure failed to lure her back. What a loss it is to turn a deaf ear to what aforementioned radio actor Joe Julian called “an exotic accent” and a “strong voice-presence.” Working with her in Dietrich’s lost radio series Café Istanbul (1952), Julian got a “glimpse behind the public image” and discovered

a woman of strength, warmth, and intelligence, yet so spontaneous that when, during a rehearsal, she overheard one of the actors express doubt that the rest of her body [she was in her early fifties by then] was as youthful as her famous legs, she ripped open her blouse to prove him wrong.

On this day, 8 October, in 1939, Dietrich could provide no such proof of her health and vitality. Scheduled to appear on the Screen Guild program that night, she was forced to call in sick due to a severe cold that, according to Roger Prior, host of the show, had halted the shooting of Dietrich’s comeback feature Destry Rides Again. The star had tried to honor her commitment, but had lost her voice entirely during rehearsals. In what must be one of the most inept voice-overs in Hollywood history, the Screen Guild producers replaced her with . . . Zasu Pitts.

It was all for laughs, of course. After all, Pitts’s voice had about as much sex appeal as fingernails being painstakingly filed . . . with a blackboard. And by casting Pitts opposite the less-than-expressive Gary Cooper, the Guild made the most of this emergency situation. “Is that Marlene Dietrich?” Cooper inquired. The affirmative only produced a terse “Well, so long.” Trying to explain the situation, Prior informed Cooper that “Zasu has Marlene Dietrich’s lines.” “Not from where I’m standing,” Cooper retorted. Together with Bob Hope and the actress billed as “Marlene Zasu Dietrich Pitts”, he nonetheless condescended to co-star in the sketch “The Girl of the Woolly West; or, She Was Wearing Slacks, So She Died Like a Man.” It sure made audience’s anxious for Dietrich’s return.

Nine years later to the day, on 8 October 1948, Dietrich was once again sick—and scheduled to appear on the air. This time, though, she was able to perform her role, cast as she was as the ailing Madame Bovary in the Ford Theater presentation of the novel as adapted by NBC staff writers Emerson Crocker and Brainerd Duffield . Sure, you’ve got to take Madame Bovary with “a pinch of power”; but you won’t be sorry to hear Dietrich breathe her last on the occasion. Besides, who could expect fidelity in the case of Emma Bovary?

“If some of Flaubert’s delicate delineation of character was missing from ‘Bovary’-on-the-air,” critic Saul Carson remarked, “Marlene Dietrich more than made up for this loss in literary flavor by her superb acting in the lead role.” Hardly carrying the chief burden, Dietrich was supported that night by Van Heflin and Claude Rains. “Too often, film stars rely on their screen reputations to cover slipshod work in radio,” Carson conceded; “but these people performed as artists who respected the medium as well as the vehicle.”

If Dietrich’s in it, just about any vehicle will do for me. Unfortunately, the extant recording does about as much justice to her timbre as Zasu Pitts. As for you, grandma, who saw trains depart for the concentration camps without making a noise, I’m just sorry that fascist propaganda robbed you of your senses . . .