I started college in the spring of 1991. I had been visiting New York City since April the previous year, returning only once to my native Germany to avoid exceeding the six consecutive months I could legally stay in the US on a tourist visa. The few weeks I spent in the recently reunited Vaterland that October had been difficult to endure, and for years I had nightmares about not getting back to the place I thought of as my elective home, the realities of the recession, the AIDS crisis, Gulf War jingoism and anti-liberal politics notwithstanding.

borrowed from a copy of Entertainment Weekly

I was determined not to repeat the experience of that involuntary hiatus once the next six-month period would come to an end. A close friend, who worked at Lehman College in the Bronx, suggested that I become a student and generously offered to pay my tuition for the first year. We decided that, instead of entering a four-year college such as Lehman, I should first enroll in classes at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), an option that would cut those “foreign” tuition fees in half.

Having gotten by thus far on my better than rudimentary German high school English, I had doubts nonetheless about my fitness for college. My first English instructor, Ms. Padol, was both exacting and reassuring. She worked hard to make her students try harder. Not only did she give us bi-weekly essay assignments, and the chance to revise them, but also made us keep a journal, which she would collect at random during the semester.

“This requirement for my English class comes almost as a relief,” I started my first entry, titled “A journal!” That it was only “almost: a relief was, as I wrote, owing to the fact that, whatever my attitudes toward my birthplace, I felt “so much more comfortable in my native language.” Back then, I still kept my diary in German.

What I missed more than the ability of putting thoughts into words was the joy of wordplay. “My English vocabulary does not really allow such extravaganzas,” I explained, “and even though the message comes through – in case there is any – the product itself seems to be dull and boring to read.” This reflects my thoughts on writing to this day. To paraphrase Gertrude Stein, I write to entertain myself and strangers.

In the days of the lockdown – which were also a time of heightened introspection – I scanned the old journal to remind myself what I chose to entertain notions of back in 1991. Many entries now require footnotes, if indeed they are worthy of them: who now recalls the stir caused by Kitty Kelley’s Nancy Reagan biography? Not that I had actually read the book. “Nobody will use this book in a history class,” I declared. Being “a compilation of anecdotes” it had “no value as a biography.” Autobiography, being predicated on the personal, cannot be similarly invalidated, as I would later argue after taking a graduate course in ‘self life writing’ with Nancy K. Miller at Lehman. What I knew even in 1991 was that a journal was not a diary.

Unlike the diary, the journal provided me with a chance to develop a writerly persona. I was playing the stranger, and what my reader, Ms. Padol, may have perceived to be my outsider perspective on what, in one entry, I called the “American waste of life” was in part my rehearsal of the part I thought my reader had reason to expect from me. However motivated or contrived, that performance tells me more about myself than any posed photograph could.

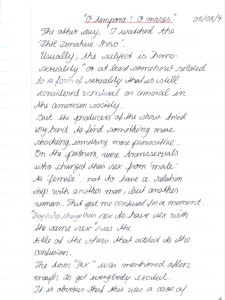

In an entry dated 3 May and titled “O tempora! O mores!” I shared my experience watching Donahue, a popular talk show at the time, named after its host. The broadcast in question was “People Who Change Their Sex to Have Sex with the Same Sex,” the sensationalism of which offering served as an opportunity to air my queer views as well as the closet of a journal that, for all its queerness, opened by lexically straightening my life by declaring my partner to be a “roommate.”

After expressing my initial confusion about the title and my indignation about the “exploitation” of the subject, I considered my complicity as a spectator and confronted the narrow-mindedness of my binary thinking:

Like the audience in the studio I asked myself why anybody would go through such a procedure only to have a lesbian relationship.

But then I realized that this is really a very shallow, stupid and yet typical question that shows how narrow-minded people are.

It also reflects ongoing intolerance in this society.

The woman in question made it clear that there is a difference between sexual identity and sexual preference. When a man feels that he is really a woman most people think that he consequently must be a homosexual.

I refer to myself in the journal as gay. What I did not say was how difficult it had been for me to define that identity, that, as a pre-teen boy I had identified as female and that, as a teenager, I had suffered the cruelty of the nickname “battle of the sexes,” in part due to what I know know (but had to look up again just now) as “gynecomastia”: the development of breast tissue I was at such pains to conceal that the advent of swimming classes, locker rooms and summer holidays alike filled me with dread. I had been a boy who feared being sexually attractive to the same sex by being perceived as being of the opposite sex.

Reading my journal and reading myself writing it thirty years later, I realise how green – and how Marjorie Taylor Green – we can be, whether in our lack of understanding or our surfeit of self-absorption, when it comes to reflecting on the long way we have supposedly come, at what cost and at whose expense. We have returned to the Identity Politics of the early 1990s, which I did not know by that term back then but which now teach in an art history context; and we are once again coming face to face with the specter of othering and the challenge of responding constructively to difference. I hope that some of those struggling now have teachers like Ms. Padol who make them keep a journal that encourage them to create a persona that does not hide the self we must constantly negotiate for ourselves.

There is no record online of a Ms. Padol having worked at BMCC. Then again, there is no record of my adjunct teaching at Lehman College from around 1994 to 2001, or at Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center thereafter. The work of adjuncts, and of teachers in general, lives on mostly in the minds and memory of the students they shaped.

I was more surprised at not finding any references online to that particular Donahue broadcast, except for a few mentions in television listings – two, to be exact. The immediate pre-internet years, that age of transition from analog to digital culture, are a time within living memory to the access of which a minor record such as my English 101 journal can serve as an aide-memoire. Whatever the evidentiary or argumentative shortcomings of anecdotes, by which I do not mean the Kitty Kelleyian hearsay I dismissed as being “of no value,” historically speaking, they can be antidotes to histories that repeat themselves due to our lack of self-reflexiveness.

Those of us who have been there, and who feel that they are there all over again – in that age in which the literalness of political correctness was pitted against the pettiness of illiberal thinking – can draw on our recollections and our collective sense of déjà vu to turn our frustration at the sight of sameness into opportunities for making some small difference: we are returning so that those who are there for the first time may find ways of moving on. Instead of repeating the question in exasperation, we need answers to “What were we thinking?”