Olympe Bradna is a diplomat of the first rank!” So declared the editors of Cinegram in an issue devoted to Say It in French. In that now largely forgotten romantic comedy, Bradna co-starred as a French student who impersonates a maid to be close to an American lover (played by Welshman Ray Milland) expected to marry a millionaire’s daughter (Irene Hervey) to save his father’s business.

Maybe that sounded better in French, in which the comedy was first staged under the title Soubrette. Never mind. The “petite morsel of feminine allure,” so the Bradna legend goes, had “only been kissed by two men during her whole lifetime”—that lifetime amounting to eighteen years back in 1938.

One year into her brief Hollywood career, Bradna had overcome her “anxiety and embarrassment” and forgotten about her vow that she “would never kiss” at all, “either on the screen or off, until she had a ‘steady’ beau.” Having been teamed with both Milland and Gene Raymond (in Stolen Heaven), the actress was “all in favour” of on-screen romance; but, when asked whose lips she preferred, the teenager refused to kiss and tell. “If I did that, it would be, how do you say? ‘propaganda.’”

In the context of European pre-war clamour and the business of Hollywood glamour, the word choice is peculiar, especially since Cinegram was a promotional effort aimed at British audiences. It is a telling statement, too, as it suggests Bradna’s questioning of the role she was expected to play in the propagation and exploitation of her own image.

Far from naive, the French-born performer knew all about the real world of make-believe, which is why, in her future pursuit of “real romance,” she was determined to “go outside the show business.” In the early 1920s, her parents, Jeanne and Joseph Bradna, had a successful bareback riding act at the Olympia Theater in Paris, after which venue Olympe was named and where she made her stage debut when she was not quite two years old. Hence, I suppose, her expressed need for security: “[A]ctors are fellows with uncertain jobs. They’re generally honest, gay, intelligent and interesting, but they lack that quality of stability that is so important to a girl who wants to establish a home.”

Presumably, she said all this in English, rather than in her native tongue. When she first set her dancing feet on the United States as a member of the Folies Bergère and subsequently performed at New York’s French Casino, she was so dismayed at her “lack of English that she determined to learn to speak the language properly. She succeeded so well,” Cinegram readers were told, “that when it came to making this new picture she had to put in several weeks of hard work under a French tutor to get her French back to standard.” A Hollywood standard, that is. After all, in romantic comedy, a French accent was as desirable as a maid’s uniform.

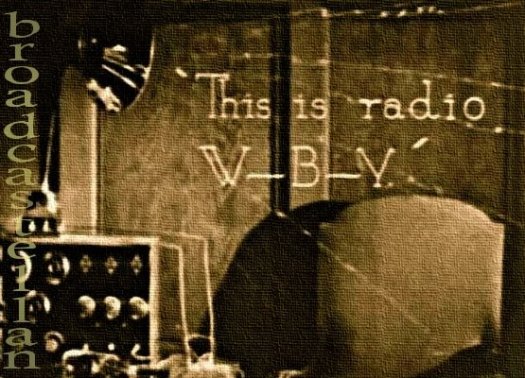

Bradna’s language skills were put to the ultimate test when, on 14 November 1938, she went behind the microphone for the Lux Radio Theater production of “The Buccaneer,” co-starring Clark Gable as French pirate Jean Lafitte; but her part was suitably Old-World, and all over the map besides, to account for any foreignness in her speech. Bradna assumed the role of Gretchen, which had been played on screen by the Hungarian-born cabaret artist Franciska Gaal. “Oh, I don’t know how I sound, Mr. DeMille,” Bradna said to in the nominal producer of the program during her scripted curtain call, “a Dutch girl with a French accent in an American play.” Supported as she was by Gertrude Michael and Akim Tamiroff, both of whom enriched American English with peculiar accents and inflections, she hardly stood out like a sore tongue.

Not that Bradna, who appeared on the cover of the 27 July 1938 issue of Movie-Radio Guide, was a stranger to the microphone. According to the March 1938 issue of Radio Mirror, Paramount Pictures “put her into five consecutive radio guest-spots for a big build up—but without giving her a nickel.” Perhaps, DeMille would not have given her a nickel, either, for the privilege of making it into a Lux-lathered version of The Buccaneer, one of his own productions, nor given her an opportunity to promote her latest picture, Say It in French, had he known what British Cinegram readers gathered by flicking through their souvenir program for Say It. Bradna, they were told, had “startled experts by announcing that the secret of her facial complexion [was] a daily buttermilk massage.”

The makers of Lux Toilet Soap could not have been pleased at Bradna’s insistence, fictive or otherwise, that buttermilk was “all” she needed: “My skin may be ever so parched and dry before the routine, but afterwards it is as fresh and smooth as I could want!

Wally Westmore, Paramount’s make-up chief, reputedly explained that the “secret”—an age-old French recipe for a youthful complexion perhaps not quite so difficult to achieve at the age of eighteen—lay in the rich oil content of buttermilk, which had the same “softening and freshening effect upon the skin as the most elaborate and expensive preparations used by the stars.” That, of course, was just the claim Lever Brothers were making each week on the Lux Radio Theater, which might explain why Ms. Bradna was never again heard on the program, whose stars were handsomely remunerated for their implied or stated endorsement of the titular product. Perhaps, Bradna was not “a diplomat of the first rank” after all . . .

Olympe Bradna died on 5 November 2012 in Lodi, California.

There would have been no soap—and no soap operas—if we didn’t have trepidations about not being quite fresh, anxieties that were over-ripe for commercial exploitation. In the US, tuners-in of the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s were constantly being alerted to the dangers of B-O, reminded to ‘Lux’ their ‘dainties,’ and told to gargle before putting their kissers to the test. Lest they could endure facing guilt by omission, listeners lathered up with products like White King toilet soap, the box tops of which they collected and sent in to broadcasters as ocular proof of their hygienic diligence, for which cumulative evidence they were duly awarded various prizes (or premiums).

There would have been no soap—and no soap operas—if we didn’t have trepidations about not being quite fresh, anxieties that were over-ripe for commercial exploitation. In the US, tuners-in of the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s were constantly being alerted to the dangers of B-O, reminded to ‘Lux’ their ‘dainties,’ and told to gargle before putting their kissers to the test. Lest they could endure facing guilt by omission, listeners lathered up with products like White King toilet soap, the box tops of which they collected and sent in to broadcasters as ocular proof of their hygienic diligence, for which cumulative evidence they were duly awarded various prizes (or premiums).