There I stood, in the shimmering sands of Coronado Beach, California. I had come, of course, to see the famous Hotel—and to share the views once taken in by Marilyn Monroe during the filming of Some Like It Hot. Marilyn was here. Now I was.

Footsteps. Sand. The old hourglass. I won’t indulge in such clichés here; but there is something pathetic about this kind of out-of-sightseeing, this belated catching up and impossible reaching out to which I am prone. The inclination to seek out what is long gone is more than morbid curiosity: it is an approach to life as a retreat from living in which even the here-and-now becomes dreamlike and chimerical. How did this get to be my way of not facing the world?

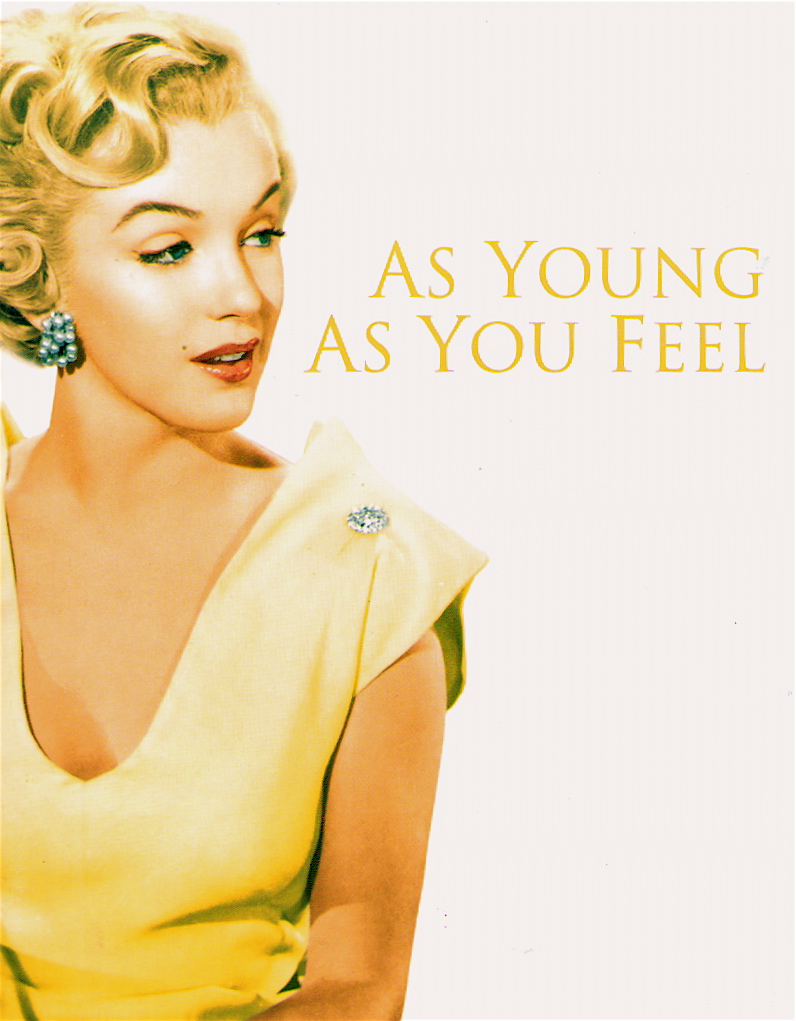

Marilyn Monroe died before I was born; yet her life and times became a fascination of my teenage years. Mine were not erotic fantasies. I did not long for her body. Nor did I think of her as being gone. She was never absent for long from the television screen, ever present on the iconic posters I pinned onto the wall above my bed. Records spinning on the old turntable, her voice filled my room. I had no regrets about never being able to meet her in the flesh; rather, it was a relief.

The wonder of her incorporeal existence made living in the body I loathed more tolerable; and it made the physical relationships I dreaded easier to contemplate in the abstract. Marilyn—and we call her by her first name because she is more familiar than famous, more girl than goddess—was not some facile paradox: “I Wanna Be Loved by You” and “I’m Through with Love” she sings in the same movie, expressing the hurt and hunger that are far from mutually exclusive.

Our teenage selves are preoccupied with the demands that both nature and society make on us, propositions and impositions captured in that horrible phrase haunting and taunting us until death: “grown up.” As a response to and rejection of the implied threat—the finality and premature stunting of our infinite potentialities—Marilyn’s afterlife was as much a reproof of society as it was a society-proof alternative: a twilight life, expired and undying, bright though snuffed out, a fragile, indomitable spirit-presence in whose shadowy glow I could luxuriate, just as many a young person nowadays revels in the gothic gloom inhabited by zombies and vampires, except that my imaginings transported rather than dispirited me.

No doubt, this twisted bent of casting myself into times preceding my birth is born of a desire to bring forth alternate selves of mine without having to bear the vagaries of the present or the uncertainties of the future. Like a life presumably squandered in reverie, bending the past to our will is a testament to a vestigial will power—or would-be power—in which the retrospective becomes invested with the prospect of an ever glimmering what if . . .

Having just returned from a trip to Niagara Falls, I was eager to revisit Henry Hathaway’s 1953 technicolor thriller starring Marilyn Monroe. Shrewd, sexy, and sensational, the expertly lensed Niagara is the most brilliantly devised star-making spectacle of Hollywood’s studio era. It has so much going for it that it can afford to be utterly predictable. The Falls are predictable, which does not make them any less exciting. And as much as I enjoy spotting old-time radio performers like the

Having just returned from a trip to Niagara Falls, I was eager to revisit Henry Hathaway’s 1953 technicolor thriller starring Marilyn Monroe. Shrewd, sexy, and sensational, the expertly lensed Niagara is the most brilliantly devised star-making spectacle of Hollywood’s studio era. It has so much going for it that it can afford to be utterly predictable. The Falls are predictable, which does not make them any less exciting. And as much as I enjoy spotting old-time radio performers like the