I had not long arrived in sweltering New York City for a month-long stay in my old neighbourhood on the Upper East Side when I learned that, across the pond, in my second adopted home in Wales, the painter Claudia Williams had died at the age of 90. I first met Williams in 2005. She was conducting research on a series of drawings and paintings commemorating the flooding of a rural Welsh community to create a reservoir designed to benefit industrial England. With my husband and frequent collaborator Robert Meyrick, who had known Williams for years and staged a major exhibition on her in 2000, I co-authored An Intimate Acquaintance, a monograph on the painter in 2013.

A decade later, an article by me on Williams’ paintings was published online by ArtUK on 28 May 2024; and just days before her death on 17 June 2024, I had been interviewed on her work by the National Library of Wales. So, when given the opportunity to write a 1000-word obituary for the London Times, I felt sufficiently rehearsed to sketch an outline of her life and career, as I had done previously on the occasion of her artist-husband Gwilym Prichard’s death in 2015.

Lunch in the yard with Gwilym Prichard and Claudia Williams

All the same, I was concerned that it might be challenging to write another “original” essay, as stipulated by the Times, on an artist about whom I had already said so much and whose accomplishments I was meant to sum up without waxing philosophical or sharing personal reminiscences. In an obituary, salient facts are called for, in chronological order, as is a writer’s ability to determine on and highlight the essentials.

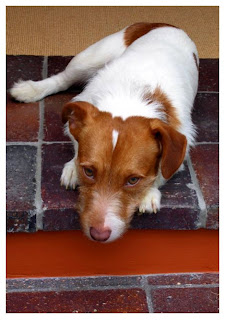

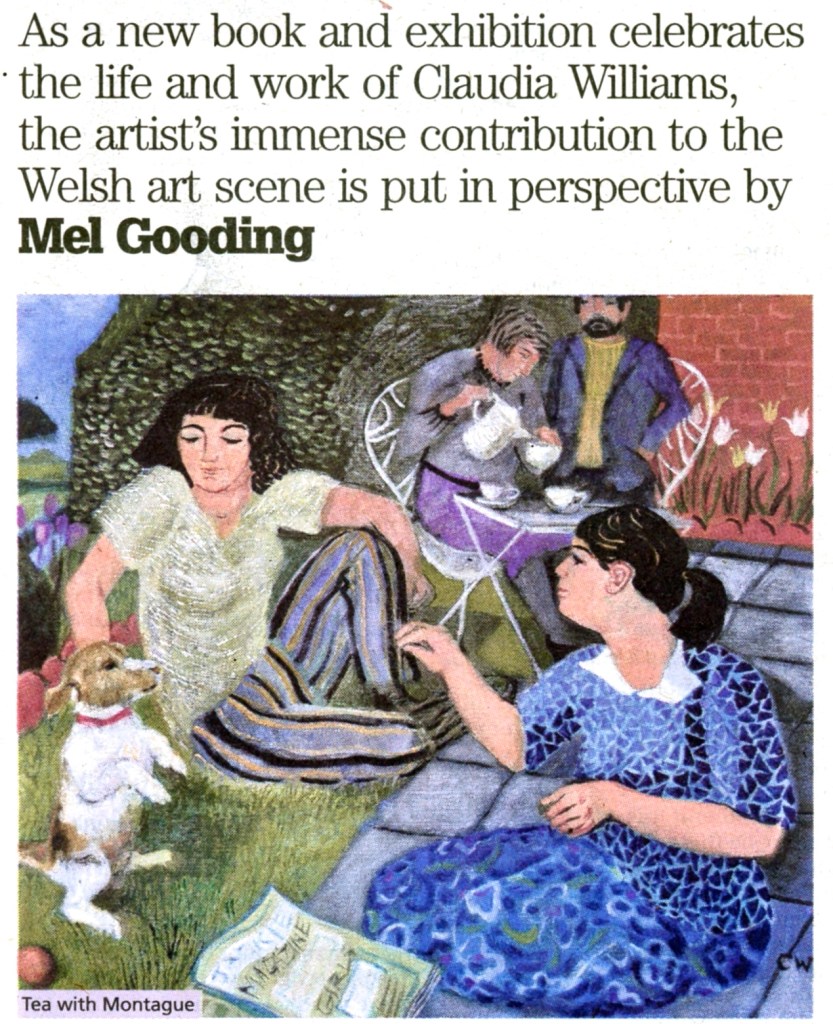

So I omitted recalling the enjoyment Williams derived from watching my Jack Russell terrier begging for food on his hind legs, a sight that inspired her painting Tea with Montague, or the “Mon Dieu” emanating from our bathroom when Williams and her husband, both in their seventies, intrepidly and jointly stepped into the whirlpool bathtub – slight episodes that, for me, capture Williams’ joie de vivre and her enthusiasm for the everyday.

Clipping of a newspaper article on An Intimate Acquaintance featuring my dog Montague as painted by Claudia Williams

In preparation for the monograph, Williams had entrusted me with her teenage diaries and other autobiographical writings, which meant there was plenty of material left on which to draw. Rather than commenting authoritatively on her contributions to British culture, I wanted to let Williams speak as much as possible in her own voice, just as her paintings speak to us, even though we might not always realize how much Williams spoke through them about herself.

What follows is the tribute I submitted to the Times.

Continue reading ““[P]eople are always interesting wherever they are”: My Tribute to Claudia Williams for the London Times”

“. . . and visited the Sea.” I have not read the poetic works of Emily Dickinson in many a post-collegiate moon; yet, as wayward as my memory may be, I never forgot those glorious opening lines. You might say that is has long been an ambition of mine to utter them, to experience for myself the magic they evoke; but, until recently, I have failed on three accounts to follow Emily in her excursion. That is, I had no dog to take along; nor did I never live close enough to the sea to approach it on foot, at least not with the certain ease that might induce me to undertake such a venture.

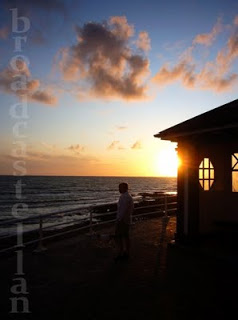

“. . . and visited the Sea.” I have not read the poetic works of Emily Dickinson in many a post-collegiate moon; yet, as wayward as my memory may be, I never forgot those glorious opening lines. You might say that is has long been an ambition of mine to utter them, to experience for myself the magic they evoke; but, until recently, I have failed on three accounts to follow Emily in her excursion. That is, I had no dog to take along; nor did I never live close enough to the sea to approach it on foot, at least not with the certain ease that might induce me to undertake such a venture. Besides, as Victorian storyteller Cuthbert Bede once remarked, it is “well worth going to Aberystwith [. . .] if only to see the sun set.” So, I’m starting late instead and take my dog for evening visits to the sea. No “Mermaids” have yet come out of the “basement” to greet me; nor any of those bottlenose dolphins that are on just about every brochure or poster designed to boost the town’s tourist industry. They are out there, to be sure; but unlike Ms. Dickinson, I’m not taking the plunge to get up close and let my “Shoes [ . . .] overflow with Pearl” until the rising tide “ma[kes] as He would eat me up.”

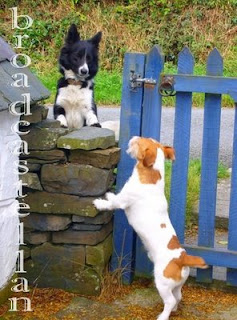

Besides, as Victorian storyteller Cuthbert Bede once remarked, it is “well worth going to Aberystwith [. . .] if only to see the sun set.” So, I’m starting late instead and take my dog for evening visits to the sea. No “Mermaids” have yet come out of the “basement” to greet me; nor any of those bottlenose dolphins that are on just about every brochure or poster designed to boost the town’s tourist industry. They are out there, to be sure; but unlike Ms. Dickinson, I’m not taking the plunge to get up close and let my “Shoes [ . . .] overflow with Pearl” until the rising tide “ma[kes] as He would eat me up.” On this sunless Tuesday morning, though, I started just early enough to keep Montague’s appointment with the veterinarian. No walk along the promenade for the old chap, to whom the change of schedule was no cause for suspicion. Now, I don’t know what possessed me to agree to his being anesthetized to have his teeth cleaned, other than Montague’s stubborn refusal to permit us to brush them. I trust that, once he has forgiven me for this betrayal of his trust, that we have many more late starts to meet and mate with the sea . . .

On this sunless Tuesday morning, though, I started just early enough to keep Montague’s appointment with the veterinarian. No walk along the promenade for the old chap, to whom the change of schedule was no cause for suspicion. Now, I don’t know what possessed me to agree to his being anesthetized to have his teeth cleaned, other than Montague’s stubborn refusal to permit us to brush them. I trust that, once he has forgiven me for this betrayal of his trust, that we have many more late starts to meet and mate with the sea . . .

Well, I am not one to multitask. I can only manage one thing at a time, which, if desirous to veil my ineptitude, I would turn into a virtue by declaring myself to be merely anxious to give everything my all. In fact, undivided attention is not easily achieved when keeping on track means struggling not to drown in the crosscurrents of concurrency. I find it hard to read in public places, cannot tie my laces without keeping my eyes on them, and have trouble talking on the phone while being in a state of motion. I may very well be incapable of growing what is commonly referred to as “up.” Going about life with such deliberation, it would take me too long to take all the requisite steps.

Well, I am not one to multitask. I can only manage one thing at a time, which, if desirous to veil my ineptitude, I would turn into a virtue by declaring myself to be merely anxious to give everything my all. In fact, undivided attention is not easily achieved when keeping on track means struggling not to drown in the crosscurrents of concurrency. I find it hard to read in public places, cannot tie my laces without keeping my eyes on them, and have trouble talking on the phone while being in a state of motion. I may very well be incapable of growing what is commonly referred to as “up.” Going about life with such deliberation, it would take me too long to take all the requisite steps. The next voice you hear will still be mine; but it will come to you from the metropolis. Tomorrow morning, I am leaving Wales (my man and Montague, the latter, being more compact, pictured in my arm). After a stopover in Manchester, England, it’s off to New York City, my former home of fifteen years. Last time I was there, I found myself in the middle of an old-time radio serial (

The next voice you hear will still be mine; but it will come to you from the metropolis. Tomorrow morning, I am leaving Wales (my man and Montague, the latter, being more compact, pictured in my arm). After a stopover in Manchester, England, it’s off to New York City, my former home of fifteen years. Last time I was there, I found myself in the middle of an old-time radio serial (