“You’re sorry?” That was the rather pitiful catchphrase devised for a certain “lovable lady of stage, screen, and radio”—Miss Charlotte Greenwood, who, having done well for herself on stage and screen, added “radio” to her resume in June 1944, when the Charlotte Greenwood Program was first broadcast over NBC’s Blue network as a summer replacement for Bob Hope. Actually, Greenwood had been Mrs. to Mr. Martin Broones for nearly two decades; but whenever another character in her serialized situation comedy addressed her as Mrs.—an assumption based, no doubt, on her far from youthful appearance—and apologized after being duly corrected, Greenwood replied in the fashion of a frustrated spinster by letting off the above retort.

Sorry, indeed. In the fall of 1944, when Hope returned to the airwaves, Greenwood was presented with a vehicle that—after the disappointment of not starring in Oklahoma!, in a part written expressly for her, no less—must have been as thrilling to her as walking off with the unclaimed favors from a cancelled party. It sure wasn’t a surrey with a fringe on top. There’s no way you could confuse that fabulous Broadway hit with the miss that was The Charlotte Greenwood Show (1944-1946), even though the compiler of one Encyclopedia of American Radio did just that, claiming the lovable one was starred “as eccentric Aunty Ellen [sic] from Oklahoma.”

Instead, Charlotte Greenwood was playing Charlotte Greenwood—an actress preparing for her next movie role as a reporter by womanning the desk in the local room of a small-town newspaper. So, for about two and a half months, Greenwood talked long-distance to her manager in Hollywood or had some confrontation or other with the city editor.

Greenwood should have spent more time talking to the show’s head writers—Jack Hasty, who, as stated in the April 22-28 issue of Radio Life (from which the above picture was taken) had previously fed lines to Al Pearce and Dr. Christian, and Don Johnson, who had been one of Fred Allen’s gagmen. Else, she might have had a heart-to-heart with her real-life manager, who also doubled as her real-life spouse. And they all should have had a word with the sponsor, or, rather, the advertising agency handling the Halls Brothers account, since their executives insisted on having a card like Greenwood dispense sentiments as hackneyed as anything printed on cardboard bearing the Hallmark label:

“Friends,” she addressed the listening public in November 1944, a couple of weeks before Thanksgiving,

for most of us, these busy days are filled with big jobs to be done, big problems to be solved. There’s so little time for the tiny, little everyday things. The neighborly chat, the letter to an old friend. And yet, in this swiftly moving world, friendship need not be forgotten. A few words that say “I hadn’t forgotten” may mean more than you know to someone, somewhere. There’s an old saying I think all of us should remember: The way to have friends is to be one.

More offensive than such platitudes is the opportunism apparent in advertising copy urging home front folks to drop a line to those on the frontlines, like this reminder from October 1944:

Friends, there has never been a time when so many families were disunited, separated by thousands of miles from those they love. Our top-ranking officers have told us again and again, there’s nothing so important to our boys and girls as mail from home. So, look around you today. Think of some boy or girl out there who would like to hear from you—and do something. Send something [. . .]

It was left to announcer Wendell Niles to suggest that the “something” in question ought not to be just anything, at least not if listeners truly “cared to send the very best.”

Quite early on in the program’s run, there must have been some debate about its appeal and prospects. As the year 1944 drew to a close, Charlotte Greenwood’s fictional film career came to an abrupt end—as did her musical interludes that had enlivened proceedings—when her character claimed an inheritance that convinced her to retire. The enticement? The Barton estate, replete with a trio of orphans now in her charge.

“You mean, to have three children, all I have to do is just read and write?” Greenwood exclaimed on 31 December 1944. “Oh, judge, isn’t education wonderful!” Perhaps, producers counted rather too much on the lack of education among the viewers. The advent of the minors sure wasn’t a belated Christmas miracle—and the retooled Greenwood vehicle was no immaculate contraption.

Softening the quirky Greenwood persona by placing three orphans in Aunt Charlotte’s lap, the sponsors may well have hoped to win the ratings war by riding the wave of popular sentiment as the all but certain victory in Europe had public attention shift from defeating the enemy and supporting the troops to dealing with the underage casualties of war.

For the remainder of the program’s run—another year, to be exact—Greenwood had do deal with the problems of two teenagers (played by Edward Ryan and Betty Moran) and their prepubescent sibling (Bobby Larson), who, on this day, 3 June, in 1945, gave his Aunt Charlotte some slight grief by being late from school.

Actually, the kid’s temporary waywardness was little more than an occasion for the writers to string together a few cracks about spanked bottoms (“[H]ow can you get anything into a child’s head by pounding the other end?”) and double entendres involving the meaning of “play.”

Not sure whether to punish young Robert for having stayed out “with some boy,” as his sister suggests, Aunt Charlotte remarks: “I know a girl who’s spend her whole life trying to find some boy to play with. Mr. Anthony [the Dr. Phil of his day] called her ‘The Case of Miss C. G.’ It was very touching.” To which she adds for our but not her niece’s amusement: “And what’s more, thirty thousand privates picked her as the girl they’d most like to see marooned on a desert island with their top sergeant.”

Without a consistent tone, let alone situations consistent with the talents of the beloved comedienne, the program’s legs were far shorter than Greenwood’s interminable gams. Apparently, the figures added up as the laughs per episode, which is to say, not. “Well, I’m no expert on arithmetic either,” Charlotte’s on-air alter ego told the nephew she could not bring herself to spank. “If I knew anything about figures, would I keep the one I’ve got?”

Those who did the accounts decided not to keep what they got—and that despite the fact that the series earned Greenwood a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Instead, as Billboard correctly predicted on 22 December 1945, the Charlotte Greenwood Show would “fold as soon as cancellation [could] take effect”—well before the end of the second season—after the sponsor had decided to take over the Reader’s Digest program from Campbell’s.

Charlotte Greenwood left radio, returned to the screen—and, in 1955, she did get to play Aunt Eller after all. You’re sorry?

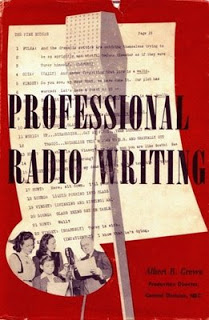

“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day,

“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day,

Well, let’s get out the matches. It’s time for some festive display of pyrotechnics. No, I am not responding to the news that Saddam Hussein has been sentenced to death for crimes against humanity. It is Guy Fawkes Day here in Britain, celebrated with rockets and bonfires lit in commemoration of a rather more decisive victory against terrorism than could be claimed in the Middle East: the foiling of a plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London back in 1605. “Remember, remember, the Fifth of November”:

Well, let’s get out the matches. It’s time for some festive display of pyrotechnics. No, I am not responding to the news that Saddam Hussein has been sentenced to death for crimes against humanity. It is Guy Fawkes Day here in Britain, celebrated with rockets and bonfires lit in commemoration of a rather more decisive victory against terrorism than could be claimed in the Middle East: the foiling of a plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament in London back in 1605. “Remember, remember, the Fifth of November”: