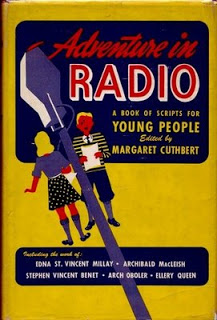

A few years ago, walking home from graduate school one afternoon, I stopped by at a second-hand bookstore in my old neighborhood of Yorkville, Manhattan. Judging from the window display, the shop seemed to specialize in children’s books and memorabilia. While this did not deter me, I hardly expected to make any significant acquisition of a volume on the subject to which this journal is chiefly devoted. I mean, I was not looking for a decoder ring or some such souvenir from the bygone age of radio dramatics. I was, after all, researching my dissertation. There was on the shelves a beautiful copy of Adventure in Radio (1945). Subtitled “A Book of Scripts for Young People,” it may be expected to include juvenile playlets written for the medium, although not necessarily produced on network radio. On such compilations, of which there are many, I was not inclined to waste money or time.

Spiting my assumptions, Adventure in Radio not only contains a number of broadcast scripts from programs like Jack Armstrong and Let’s Pretend but also propaganda plays and wartime commentaries geared toward an adult audience. In addition, it offers insights on the production of radio plays, on sound effects, announcing, and “radio language.” It took a little salestalk from the owner of the by now long closed store, but I was soon convinced. Where (I did not know much about eBay back then) would I ever find such a book again? And how could I claim to be serious about old-time radio if I did not snatch up this copy? So, I handed over my $40 (it was the price tag that made me hesitate) and walked off, eager to continue my studies . . . and determined to find the recordings to match the published scripts now at my fingertips.

That often proved quite difficult; but I had made up my mind that I was not going to write about words divorced from performance. I wanted to hear what was being done with those scripts, how they were edited and interpreted. Take the NBC University Theater’s production of “Gulliver’s Travels,” for instance. It was broadcast on this day, 24 September, in 1948. My appreciation of the challenges of soundstaging the play grew after reading the comments with which Frank Papp, a director of radio drama for NBC, prefaces the script, originally written for the series World’s Great Novels. Papp points out the “unusual problems” Frank Wells’s adaptation posed in production:

In the matter of casting, the Lilliputian was the most difficult. Here was needed a voice which gave the illusion of a tiny man. A trick voice in itself would be only a caricature. What was required was a voice that created a picture of a real human being of Lilliputian size. After extensive auditioning, an actor was found whose talent and vocal capabilities fulfilled these requirements.

The actor portraying Gulliver was placed in an isolation booth, Papp explains, “so that the Lilliputian’s voice would not spill over into his microphone” and the two voices could be miked separately, with a volume reflecting the size of each character. The voice of the King of Brobdingnag, meanwhile, was “fed” both through an electronic filter to amplify its base quality and through NBC’s largest echo chamber to create the illusion of a giant.

The 24 September 1948 presentation of “Gulliver’s Travels,” starring Henry Hull in the title role, does not quite live up to the expectations raised by Papp’s introduction. Under the direction of Max Hutto, child actor (Anthony Boris) is cast in the role of the Lilliputian, a choice that infantilizes the character and renders pointless the effects achieved by the sound engineer.

While Wells’s script downsizes Swift’s story and diminishes its bitterness and bite, it is the production that contributes to a sense that Gulliver’s Travels is, at heart, a juvenile fantasy, despite its airing on the ambitious if misguided NBC University Theater, a program that linked listening to such bowdlerizations with courses in distant learning. I may have been able to match the script with a production, but it was not the one described in Adventure in Radio.

Squeezed as I am into the isolation booth of my preoccupations, it is my mind’s voice that supplies the lilt of the Lilliputian . . .

Now, I am not going to get all sentimental and give you the old “tempus fugit” spiel; but I’d like to mention, in passing, that this post (the 355th entry into the journal) marks the beginning of a third year for broadcastellan. Meanwhile, I am resting with a bad back—in the city that never sleeps, of all places. This afternoon, during an inaugural transatlantic video conference with my two faithful companions back home in Wales, my mind excused itself from my heart and took off in reflections about the ways in which technology has assisted in forging a bond between the US and its close ally across the pond, and the degree to which such tele-communal forgings may come across as mere forgeries when compared to the real thing of an actual encounter.

Now, I am not going to get all sentimental and give you the old “tempus fugit” spiel; but I’d like to mention, in passing, that this post (the 355th entry into the journal) marks the beginning of a third year for broadcastellan. Meanwhile, I am resting with a bad back—in the city that never sleeps, of all places. This afternoon, during an inaugural transatlantic video conference with my two faithful companions back home in Wales, my mind excused itself from my heart and took off in reflections about the ways in which technology has assisted in forging a bond between the US and its close ally across the pond, and the degree to which such tele-communal forgings may come across as mere forgeries when compared to the real thing of an actual encounter. I came across a peculiar piece of schlock science today. An evolutionary theorist has uttered the prediction that, within about 100,000 years from now, the human race

I came across a peculiar piece of schlock science today. An evolutionary theorist has uttered the prediction that, within about 100,000 years from now, the human race