I am not an academic. I am a human being. That’s not just me misquoting The Elephant Man. It is a cri de cœur expressive of what is at the core of my identity as a creative person who happens to have transmogrified into an art history lecturer. To interrogate what that even means, I teach “Gothic Imagination” at the School of Art, Aberystwyth University.

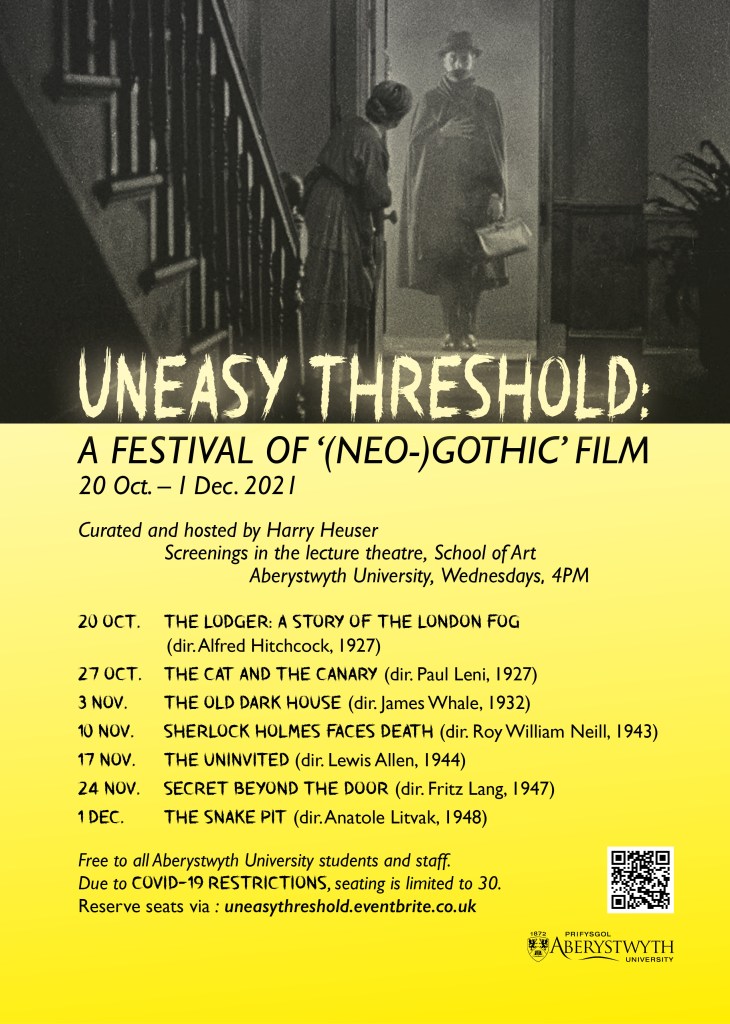

As part of that class, I present an extracurricular series of film screenings exploring the boundaries of the ‘gothic’ beyond the furnishings of the genre ‘Gothic.’ That ‘gothic’ is a term so broadly applied and ill-defined as to render it practically useless is a by now thoroughly predictable way of opening a debate about its practical uses. Then again, the gothic has little to do to with practicalities.

I have no intention to make the term, “salonfähig,” that is, reverting here to my native German, to make it acceptable or viable in an academic setting. Rather, I use the word, which I am applying to visual culture instead of literature, to contest progress or avant-garde narratives traditionally espoused by academies in order to suggest alternative histories and alternatives to the teaching of art history. Attention to the popular, presumably lesser arts is essential to this strategy.

The first series of screenings, coinciding with my previous iteration of “Gothic Imagination,” was titled “Treacherous Territories.” The phrase was meant to capture that challenge of defining and the dangers of inserting a mutable term such as ‘gothic’ into the lecture theaters and seminar rooms that cannot quite accommodate, let alone confine it.

The current series, “Uneasy Threshold,” continues that playful investigation. What, for instance, carries a mystery or a romance over the threshold of ‘gothic’? What is that threshold? And what is the ‘gothic’ interior – the environment in which ‘gothic’ may be contained both as a subject for discussion and as an experience to be had by the viewer of, say, a crime drama, a thriller, a film noir or a horror movie?

As a literary genre, the Gothic began in and with a house – in Strawberry Hill and with the Castle of Otranto, both conceived by Horace Walpole long before Frankenstein, Jekyll/Hyde and Dracula came onto the scene. Those names are on the letter box of the Gothic mansion of our imagination, and I do not mean to evict their bearers; but might there be room as well – be it a closet, a cellar or a boudoir – for a few hundred other, less usual suspects, such as the title character of The Lodger (1927)?

The Lodger insists on moving in on the party assembled at the Gothic castle, just as the Lodger – who may or may not be a serial killer called The Avenger – emerges out of the fog. edges himself into the home of the Buntings, and comes to preoccupy their thoughts and nightmares. Invited, perhaps, but deemed suspect or queer all the same.

When the Lodger first made his appearance, in 1911, in a short story by Marie Belloc Lowndes, the figure was already lodged in the collective consciousness of urban dwellers who, like the author, were old enough to recall the Whitechapel Murders of 1888 or else were raised with the legend of Jack the Ripper, an alternative to a nursery rhyme all the more terrifying for having neither rhyme nor reason.

The Lodger transforms the story, which Belloc Lowndes turned into a novel, by pouring more sex into the mix. That the layered cake did not quite rise to Hitchcock’s satisfaction was, legend has it, due to the casting of Ivor Novello in the title role: a queer Welsh matinee idol who, Hitchcock argued, was not allowed to get away with murder but was to be pronounced blameless by virtue of his status as a star.

Whether or not that is the true reason for the direction the movie adaptation takes, it does not make the story any less intriguing – or gothic.

The Lodger is the story of a home that becomes “unhomely” – German for “uncanny.” The lodger is no architect or bricklayer; rather, he transforms the dynamics of the group of people dwelling in the house he enters. Blameless he may be, but he is an Avenger all the same, as Sanford Schwartz points out in “To-Night ‘Golden Curls’: Murder and Mimesis in Hitchcock’s The Lodger” – not the killer, but the victim of the killer avenging her death, a victim-turned-vigilante who, misunderstood, dreaded and feared, becomes the subject of her other lover’s revenge.

It is the other, ostensibly sane and safe lover, a police officer, who trespasses – who abuses his power – to trap the innocent man who threatens his supremacy as a prospective husband. The handcuffs he suits to his own pursuits prove harmful to his lover’s trust and nearly cause the death of his rival even after that rival is proven innocent of crime.

The Lodger is gothic as James’s Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824) is Gothic. It is a story of injustice and sanctioned tyranny. Like Frankenstein’s creature, the Lodger is hunted and tormented. Law, reason and morals are being questioned; and the pillars of civilisation are proven to be unsafe as houses.

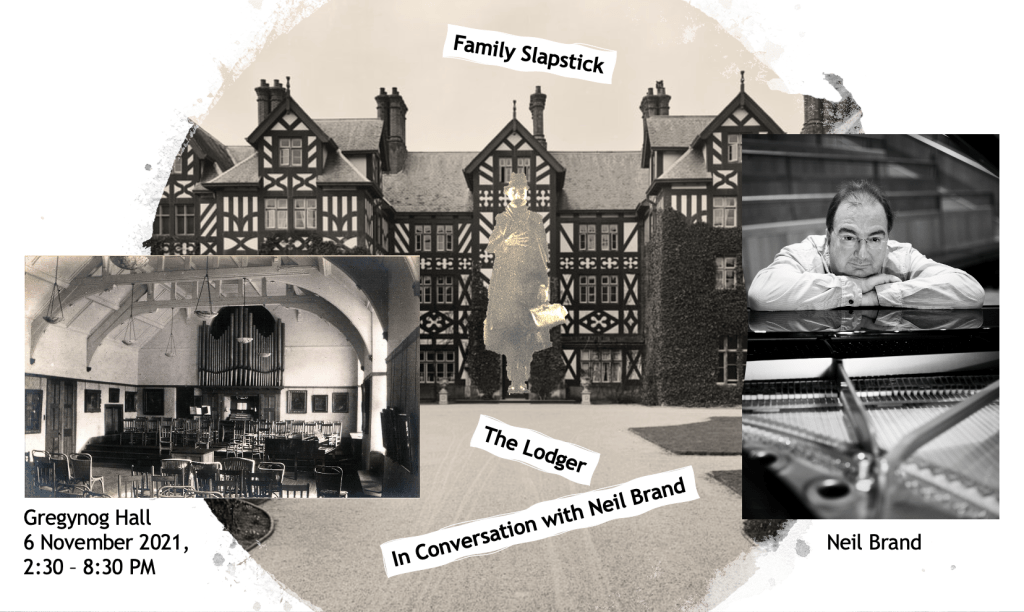

The next time I am (re)viewing The Lodger, the film will be accompanied by Neil Brand at Gregynog Hall, 6 Nov. 2021, when I shall be in conversation with the playwright-composer about silent film music and the language of pre-talkie cinema.

Well, this is Guy Fawkes Day (or Bonfire Night) here in Britain. I am hearing the fireworks exploding as I write. Last year, I

Well, this is Guy Fawkes Day (or Bonfire Night) here in Britain. I am hearing the fireworks exploding as I write. Last year, I  Generally, we don’t regard our movie comings and goings as once-in-a-lifetime events, no matter how extraordinary the experience. In fact, we are inclined to opt for a rerun if a film manages to make us wax hyperbolic in our enthusiasm for it. To be sure, not many moving images have this force; nowadays, they are so readily reproduced, so instantly retrieved, that many of us won’t even bother to sit down for them, knowing that they can be had whenever we are ready for them. We miss out on so much precisely because we are comforted to the point of indifference by the thought that we do not have to miss anything at all. When I write “we,” I do number myself among those who are at-our-fingertipsy with technology. Last weekend’s screening of The Life Story of David Lloyd George at the Fflics film festival here in Wales was a reminder that films can indeed be rare; that they are fragile and subject to forces, natural and otherwise, that cause them to vanish from view.

Generally, we don’t regard our movie comings and goings as once-in-a-lifetime events, no matter how extraordinary the experience. In fact, we are inclined to opt for a rerun if a film manages to make us wax hyperbolic in our enthusiasm for it. To be sure, not many moving images have this force; nowadays, they are so readily reproduced, so instantly retrieved, that many of us won’t even bother to sit down for them, knowing that they can be had whenever we are ready for them. We miss out on so much precisely because we are comforted to the point of indifference by the thought that we do not have to miss anything at all. When I write “we,” I do number myself among those who are at-our-fingertipsy with technology. Last weekend’s screening of The Life Story of David Lloyd George at the Fflics film festival here in Wales was a reminder that films can indeed be rare; that they are fragile and subject to forces, natural and otherwise, that cause them to vanish from view. Well, this is right up my valley, I thought, when I first heard about Fflics: Wales Screen Classics. That was back in 2005; but this month, the festival is finally getting underway here in Aberystwyth. We went into town this afternoon for the official launch; and whatever promotional boost I might give this event I am only too glad to provide, especially since it brings our friend, the

Well, this is right up my valley, I thought, when I first heard about Fflics: Wales Screen Classics. That was back in 2005; but this month, the festival is finally getting underway here in Aberystwyth. We went into town this afternoon for the official launch; and whatever promotional boost I might give this event I am only too glad to provide, especially since it brings our friend, the  The next voice you hear will still be mine; but it will come to you from the metropolis. Tomorrow morning, I am leaving Wales (my man and Montague, the latter, being more compact, pictured in my arm). After a stopover in Manchester, England, it’s off to New York City, my former home of fifteen years. Last time I was there, I found myself in the middle of an old-time radio serial (

The next voice you hear will still be mine; but it will come to you from the metropolis. Tomorrow morning, I am leaving Wales (my man and Montague, the latter, being more compact, pictured in my arm). After a stopover in Manchester, England, it’s off to New York City, my former home of fifteen years. Last time I was there, I found myself in the middle of an old-time radio serial ( Well, what does it suggest? My silence, I mean. Is it a sign of indifference or an exercise in difference? Does it bespeak failure or betoken activity elsewhere? Does it spell death, metaphoric or otherwise? Mind you, I have merely extended my customary weekend retreat from the blogosphere for a single day; and, such is the nature or curse of keeping a public journal—of being nobody to anyone—it may have gone virtually unnoticed. My absence, after all, is no more eloquent than your silence. It requires your presence to come into being.

Well, what does it suggest? My silence, I mean. Is it a sign of indifference or an exercise in difference? Does it bespeak failure or betoken activity elsewhere? Does it spell death, metaphoric or otherwise? Mind you, I have merely extended my customary weekend retreat from the blogosphere for a single day; and, such is the nature or curse of keeping a public journal—of being nobody to anyone—it may have gone virtually unnoticed. My absence, after all, is no more eloquent than your silence. It requires your presence to come into being. Well, it is supposed to be busting out all over tomorrow. June, that is—the month during which television entertainment goes bust. In the US, at least, a generally enforced leave-taking from your favorites is a programming pattern that predates television. Looking through my radio files, I came across an article in the June 1932 issue of The Forum, discussing what Americans could expect to find “On the Summer Air.” It is an interesting piece, especially since it serves as a reminder that, during the early years of broadcasting, the summer hiatus was a response to technical difficulties. The shutting down of broadcast studios, like the closing of Broadway theaters, was directly related to the rising mercury, to the heat that made the asphalt buckle and urbanites escape to their vernal retreats.

Well, it is supposed to be busting out all over tomorrow. June, that is—the month during which television entertainment goes bust. In the US, at least, a generally enforced leave-taking from your favorites is a programming pattern that predates television. Looking through my radio files, I came across an article in the June 1932 issue of The Forum, discussing what Americans could expect to find “On the Summer Air.” It is an interesting piece, especially since it serves as a reminder that, during the early years of broadcasting, the summer hiatus was a response to technical difficulties. The shutting down of broadcast studios, like the closing of Broadway theaters, was directly related to the rising mercury, to the heat that made the asphalt buckle and urbanites escape to their vernal retreats. Moving from Manhattan to Mid-Wales was bound to lower my chances of taking in some live theater now and then (not that Broadway ticket prices had allowed me to keep the intervals between “now” and “then” quite as short as I’d like them to be). I expected there’d be the odd staging of Hamlet with an all-chicken cast or a revival of “Hey, That’s My Tractor” (to borrow some St. Olaf stories from The Golden Girls). Luckily, I’m not one to embrace the newfangled and my tastes in theatrical entertainments are, well, conservative. I say luckily because even if you’’re living west of England rather than the West End of its capital, chances are that there’s a touring company coming your way, eventually.

Moving from Manhattan to Mid-Wales was bound to lower my chances of taking in some live theater now and then (not that Broadway ticket prices had allowed me to keep the intervals between “now” and “then” quite as short as I’d like them to be). I expected there’d be the odd staging of Hamlet with an all-chicken cast or a revival of “Hey, That’s My Tractor” (to borrow some St. Olaf stories from The Golden Girls). Luckily, I’m not one to embrace the newfangled and my tastes in theatrical entertainments are, well, conservative. I say luckily because even if you’’re living west of England rather than the West End of its capital, chances are that there’s a touring company coming your way, eventually.