What a tramp my mind has turned into lately. I would like to think that I still got one of my own, to have and to hold on to, for richer or poorer, and all that; but every now and again, and rather too frequently at that, the willful one takes off without the slightest concern for my state of it. It used to be that I could gather my thoughts like keepsakes to store a mind with; these days, I wonder just who’s minding the store. And just when I feel that I’ve lost it completely, there it comes ambling in, disheveled, unruly, and well out of its designated head. With a little luck, the suitcase of mementoes with which it absconded turns up again, similarly disorganized, rarely complete if at times strangely augmented. Perhaps, minds resent being crossed once too often. That has crossed mine, to be sure.

What a tramp my mind has turned into lately. I would like to think that I still got one of my own, to have and to hold on to, for richer or poorer, and all that; but every now and again, and rather too frequently at that, the willful one takes off without the slightest concern for my state of it. It used to be that I could gather my thoughts like keepsakes to store a mind with; these days, I wonder just who’s minding the store. And just when I feel that I’ve lost it completely, there it comes ambling in, disheveled, unruly, and well out of its designated head. With a little luck, the suitcase of mementoes with which it absconded turns up again, similarly disorganized, rarely complete if at times strangely augmented. Perhaps, minds resent being crossed once too often. That has crossed mine, to be sure.

Anyway, where was I going with this? Ah, yes. Straight back to New York City. The Biltmore Theatre. Make that the Samuel J. Friedman, as it is now called. Built in 1925 and steeped in comedy theater tradition, the former Biltmore is just the venue for the current revival of The Royal Family, of which production, scheduled to open 8 October 2009, I had the good fortune to catch the second preview a few weeks ago. Classic crowd-pleasers like Poppa (1929), Brother Rat (1936-38), My Sister Eileen (1940-42), and the long-running Barefoot in the Park (1963-67) were staged here, where Mae West caused a sensation in October 1928 with Pleasure Man, a play they let go on for all of two performances.

While Ethel Barrymore might have wished a similarly compact run for The Royal Family, the play amused rather than scandalized theatergoers who appreciated it as a wildly flamboyant yet precisely cut gem of wit set firmly in a mount of genuine sentiment—which is just what you’d expect from a collaboration of George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber. Histrionics, theatrical disguises, a bit of swashbuckling—this screwball of a jewel still generates plenty of sparks, even if the preview I attended needed a little polish to show it off it to its full advantage.

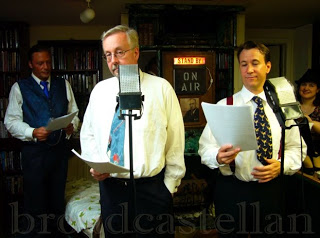

Informed that her son may have killed a man, the matriarch of the family inquires: “Anyone we know?” Among the somebodies we know to have slain them with lines like these in the past are Broadway and Hollywood royals like Otto Kruger, Ruth Hussey, Eva Le Gallienne, Fredric March, Rosemary Harris, and . . . Rosemary Harris. As is entirely in keeping with the play’s premise—three generations of a theatrical family congregating and emoting under one roof—Ms. Harris is now playing the mother of the character she portrayed back in 1975. Regrettably, unlike Estelle Winwood in the cleverly truncated Theatre Guild on the Air production broadcast on 16 December 1945, Ms. Harris as Fanny Cavendish was not quite eccentric or electric enough, although she certainly possesses the curtains-foreshadowing vulnerability her character refuses to acknowledge.

Decidedly more energetic and Barrymore or less ideally cast were the other members of the present production, which includes Jan Maxwell as Julie, Reg Rogers as Tony, Tony Roberts as Oscar, John Glover as Herbert Dean and Saturday Night Live alumna Ana Gasteyer as Kitty. Whenever the pace slackened and the madcap was beginning to resemble a nightcap or some such old hat, I could generally rely on Ms. Gasteyer’s gestures and facial expressions to keep me amused.

There was a moment, though, when my attention span was being put to the test—and promptly failed. I looked at the fresh though not especially fascinating face of Kelli Barrett (as Gwen) and found myself transported to the 1920s, those early days of the Biltmore. I started to think of or hope for a youthful, vivacious Claudette Colbert performing on Broadway at that time, a few years before she left the stage to pursue a career in motion pictures. Why, I wondered, was my mind walking off with her?

Well, eventually it all came home to me—my mind sauntering back in with a duffle bag of stuff I didn’t remember possessing—when I perused the playbill to learn about the history of the Biltmore. Colbert, I learned, had performed on that very stage back in 1927, the year in which The Royal Family was written, enjoying her first major success in The Barker. Decades later, she returned there for The Kingfishers (1978) and A Talent for Murder (1981). So, there was something of a presence of Ms. Colbert on that stage, even though she never played young Gwen.

Today, researching a little to justify what still seemed like a mere digression in a half-hearted review of the play, I discovered (consulting the index of Bernard F. Dick’s recent biography of Colbert) that the actress did get hold of a minor branch of the Royal Family tree when she seized the opportunity to portray Gwen’s mother in a 1954 television adaptation of the play. That version, the opener for CBS’s The Best of Broadway series, was broadcast live on 16 September—which happens to be the day I stepped inside the Biltmore to catch up with The Royal Family.

Perhaps it is just as well that I give in and let my mind go blithely astray. For all the exasperation of momentary lapses, of missed punch lines, plot lines or points my thoughts are beside of, the returns are welcome and oddly reassuring. Besides, the old tramp wouldn’t have it any other way . . .

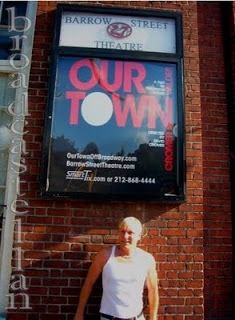

Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”

Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”