As soon as I decided to make radio plays written in the United States in the 1930s, ‘40s and early ‘50s the subject of my doctoral study, I set out to scour New York City University libraries for scripts published during that period. My degree is in English, and I was keen not to approach broadcasting as a purely historical subject. The play texts and my readings of them were to be central to my engagement with the narrative-drama hybridity that is peculiar to radio storytelling. Whenever possible, I tried to match script with recording—but, to justify my study as a literary subject, I was determined to examine as many print sources as possible. One text that promised to provide a valuable sample of 1930s broadcast writing was Radio Continuity Types, a 1938 anthology compiled and edited by Sherman Paxton Lawton.

Back in the late 1990s, when I started my research, I was too focused, too narrow-minded to consider anything that seemed to lie outside the scope of my study as I had defined it for myself, somewhat prematurely. Instead, I copied what I deemed useful and dutifully returned the books I had borrowed, many of which were on interlibrary loan and therefore not in my hands for long. It was only recently that I added Radio Continuity Types to my personal library of radio related volumes—and I was curious to find out what I had overlooked during my initial review of this book . . .

Radio Continuity Types is divided into five main sections: Dramatic Continuities, Talk Continuities, Hybrid Continuities, Novelties and Specialties, and Variety Shows. Clearly, the first section was then most interesting to me. It mainly contains scripts for daytime serials, many of which I had never heard of, let alone listened to: Roses and Drums, Dangerous Paradise, Today’s Children. There are chapters from Ultra-Violet, a thriller serial by Fran Striker, samples of children’s adventures like Jack Armstrong and Bobby Benson, as well as an early script from Gosden and Correll’s Amos ‘n’ Andy taken from the period when the program’s format was what Lawton labels “revolving plot drama.”

Aside from a melodrama written for The Wonder Show and starring Orson Welles, I got little use out of Lawton’s book, mainly because I concentrated on complete 30-minute or hour-long plays rather than on serials I could only consider as fragments. Besides, I was not eager to perpetuate the notion of radio entertainment as being juvenile or strictly commercial.

Anyway. Looking at the book now, I am struck by Lawton’s choices. Never mind the weather report on page 346 or Madam Sylvia’s salad recipe. How about the editor’s selection of “Occasional speeches”? Historically significant among them are Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first inaugural, a “Welcoming” of Roosevelt by Getulio Vargas, President of Brazil, as well as Prince Edward VIII’s announcement of his abdication.

No less significant but rather more curious are Lawton’s “Straight Talk” selections of fascist propaganda by Benito Mussolini, Joseph Goebbels and Adolf Hitler: “Long live the National Socialist German Reich!” and “Now and forever—Germany! Sieg Heil!” Surely, such lines draw attention to themselves in a volume promising readers “some of the most successful work that has been done in broadcasting.” What, besides calling Goebbels’s “Proclamation on Entry into Austria” and Hitler’s “I Return” speech (both dated 12 March 1938) “straight” and “occasional,” had the editor to say about his selections? And what might these selections tell us about the editor who made them?

In a book on broadcasting published in the US in 1938, neutrality may not be altogether unexpected, as US network radio itself was “neutral”; but Lawton—who headed the department of “Radio and Visual Education” at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri—seems to have gone beyond mere representations of “types.” Introducing a translation of Hitler’s speech, which comments on the reluctance of “international truth-seekers” to regard the new “Pan-Germany” as a choice of its people, Lawton argued it to represent “some of the best work of a man who has proved the power of radio in the formation of public opinion.” There are no further comments either on technique or intention. No explanation of what is “best” and how it was “proved” to be so. No examination of “power,” “public,” and “opinion.” It is this refusal to contextualize that renders the editor’s stamp of approval suspect.

The “continuity” Lawton was concerned with was of the “type” written for broadcasting—not the “continuity” of democracy or the free world. When he spoke of “historical value,” the editor did so as a “justification for a classification” of the kind of “continuity types” he compiled (among them “straight argumentative talks” by Senator Huey Long and Father Coughlin). And when, in his introduction, he speculated about radio in 1951 (“when broadcasting [would] be twice as old” as it was then), he did not consider what consequences the “best” and “most efficient” of “straight talk” might have on the “types” that were still “in common use” back in 1938.

Given its definition of “historical value,” it hardly surprises that Lawton’s anthology was not in “common use” for long. There was no second edition.

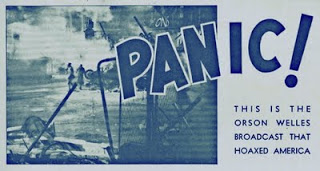

Well, it wasn’t exactly business as usual on this day, 7 December, back in 1941. Mind you, lucre-minded broadcasters tried hard to keep the well-oiled machinery of commercial radio running. There were soap operas and there was popular music, interrupted in a fashion rehearsed by “The War of the Worlds,” by updates about the developments of the attack on Pearl Harbor (

Well, it wasn’t exactly business as usual on this day, 7 December, back in 1941. Mind you, lucre-minded broadcasters tried hard to keep the well-oiled machinery of commercial radio running. There were soap operas and there was popular music, interrupted in a fashion rehearsed by “The War of the Worlds,” by updates about the developments of the attack on Pearl Harbor ( Well, this is St. Nicholas Day. Traditionally, it is the day on which children in Germany (among whom I once numbered) put their hands in their boots to find out whether Saint Nick, passing by overnight, left anything within. Preferably candy, and, given the repository, preferably wrapped. Now, it has been several decades since last I observed the custom. These days, as an every so slightly overweight atheist with somewhat of a passion for boots, I would be more pleased to find my footwear polished.

Well, this is St. Nicholas Day. Traditionally, it is the day on which children in Germany (among whom I once numbered) put their hands in their boots to find out whether Saint Nick, passing by overnight, left anything within. Preferably candy, and, given the repository, preferably wrapped. Now, it has been several decades since last I observed the custom. These days, as an every so slightly overweight atheist with somewhat of a passion for boots, I would be more pleased to find my footwear polished. When I read that Lamont Cranston is being resurrected for another big screen adventure scheduled to begin in 2010, I decided to catch up with one of the earlier Shadow plays. The Shadow, of course, always played well on the radio. On this day, 26 June, in 1938, he was again called into action when a “Blind Beggar Dies” after refusing to share his pittance with a gang of racketeers. The blind beggars alive to such melodrama and asking for more were millions of American radio listeners tuning in to follow the exploits of that “wealthy man about town” who was able to “cloud men’s minds” while opening them to the wonders of non-visual storytelling.

When I read that Lamont Cranston is being resurrected for another big screen adventure scheduled to begin in 2010, I decided to catch up with one of the earlier Shadow plays. The Shadow, of course, always played well on the radio. On this day, 26 June, in 1938, he was again called into action when a “Blind Beggar Dies” after refusing to share his pittance with a gang of racketeers. The blind beggars alive to such melodrama and asking for more were millions of American radio listeners tuning in to follow the exploits of that “wealthy man about town” who was able to “cloud men’s minds” while opening them to the wonders of non-visual storytelling.