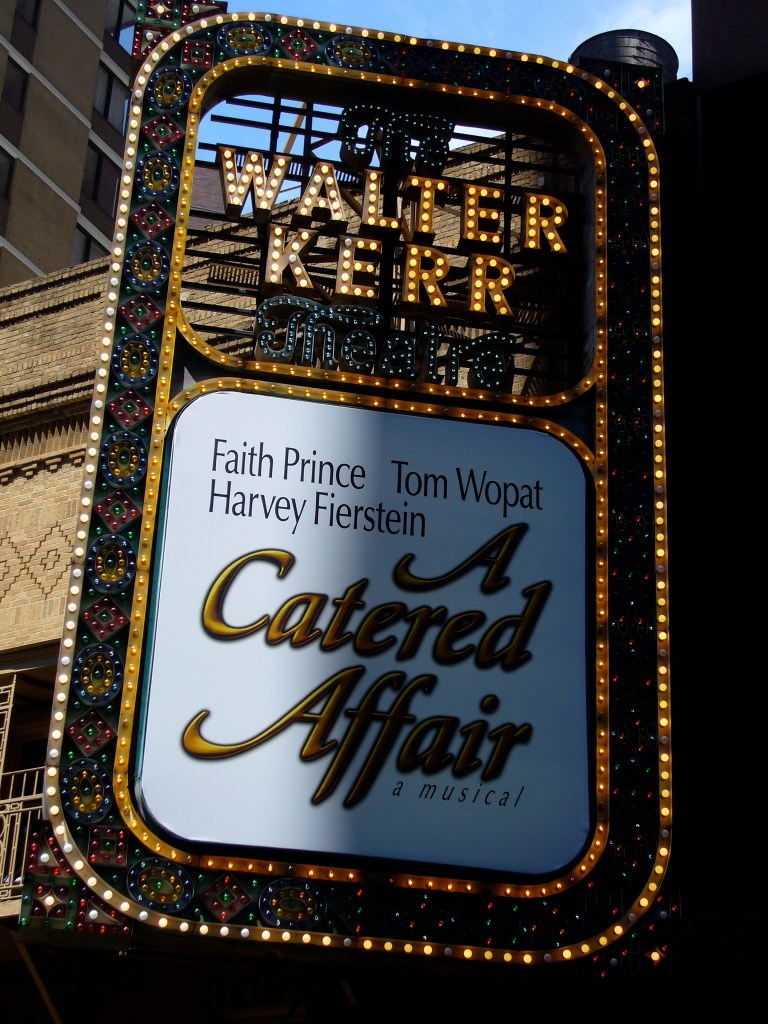

A few months ago, I went to see a Broadway musical based on a television play by Paddy Chayefsky. Confronted with those keywords alone, I pretty much knew that A Catered Affair was not the kind of razzle-dazzler that makes me want to join a chorus line or find myself a chandelier to swing from. A Catered Affair is more Schlitz than champagne, more kitchen sink than swimming pool. Drab, stale, and too-understated-for-a-thousand-seater, it left me colder than yesterday’s toast (and I said as much then).

A few months ago, I went to see a Broadway musical based on a television play by Paddy Chayefsky. Confronted with those keywords alone, I pretty much knew that A Catered Affair was not the kind of razzle-dazzler that makes me want to join a chorus line or find myself a chandelier to swing from. A Catered Affair is more Schlitz than champagne, more kitchen sink than swimming pool. Drab, stale, and too-understated-for-a-thousand-seater, it left me colder than yesterday’s toast (and I said as much then).

What made me want to attend the Affair was the chance to see three seasoned performers who, before being thus ill catered to, had been seen at grander and livelier dos: Faith Prince, Tom Wopat, and Harvey Fierstein, whose idea it was to revive and presumably update Chayefsky’s 1955 original. Last night, I caught up with the 1956 movie version as adapted for the screen by Gore Vidal. Similarly drab, but without the cliché-laden lyrics and with a more memorable score by André Previn; and starring Bette Davis, of course.

When we first see Davis’s middle-aged mother on the screen, she is performing her hausfrau chores listening to The Romance of Helen Trent, a radio soap opera that encouraged those tuning in to dream of love in “middle life and even beyond.” It was probably the quickest and most effective way of establishing the character and setting the mood. After all, Davis’s Aggie, whose own marriage is not the stuff of romance, is determined to throw her daughter the wedding that she, Aggie, never had. She is living by proxy, as through Trent’s loves and travails, a fictional character that makes it possible for Aggie to keep on dreaming.

Once again, I was thankful for my many excursions into the world of radio drama; but I also wondered whether the aging Ms. Davis and her far from youthful co-star, Ernest Borgnine, are giving me what Helen Trent promised its listeners back then: an assurance that life goes on past 35 (which, in today’s life expectancy math, translates into, say, 45).

I rarely watch or read anything with or by anyone yet living. It is not that I am morbid—it is because I prefer a certain kind of writing and movie-making. To me, whatever I read, see, or experience is living, insofar as my own mind and brain may be considered alive or capable of giving birth. So, when I followed up our small-screening of The Catered Affair by the requisite dipping into the Internet Movie Database, I was surprised to see that, aside from André Previn, three of its key players are not only alive but still active in show business.

The unsinkable Debbie Reynolds (no surprise there), the Time Machine tested Rod Taylor (next seen as Winston Churchill in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds), and the indomitable Mr. Borgnine, who has five projects in various stages of production. Not even cats can count on Borgnine lives. To think that, having played a middle-aged working man some five decades ago and still going strong today is both inspiring and . . . exasperating.

Why exasperating? Well, the media contribute to or are responsible for the disappearing act of many an act over the age of, say, fifty (or anyone who looks what we think of as being past middle aged, no matter how far we manage to stretch our earthly existence or Botox our past out of existence these days). You might repeat or even believe the adage that forty is the new thirty, but in Hollywood, sixty is still the same-old ninety. Sure, there are grannios (cameos for the superannuated) and grampaparts in family mush or sitcoms; but few films explore life beyond fifty without rendering maturity all supernatural in a Joan Collins sort of way.

Helen Trent and the heroines of radio were allowed to get old because audiences did not have to look at—or past—the wrinkles and liver spots. High definition, I suspect, is only taking us further down the road of low fidelity, away from the age-old romance that is the reality of life.