Eve Arden is Our Miss Brooks. Joan Collins is Alexis. Estelle Getty, Sophia. Whatever else these ladies did in their long stage, screen and television careers, they have become identified with a single, signature role they had the good fortune to create in midlife. Grabbing their second chances at a second skin, they experienced a regenerative ecdysis. The character or caricature that emerges in the process obscures the body of work thus transformed. Another such anew-comer coming readily to mind is Patricia Routledge, who, for better or worse, makes us forget that she has ever done anything else before or since she took on the role of Hyacinth Bucket in Keeping Up Appearances back in 1990. Would she forever keep up the charade, or might she yet have the power to make this our image of her disappear? Could she spring to new lives by kicking that Bucket? Those questions were on my mind when we drove up to the ancient market town of Machynlleth, here in mid-Wales, where Ms. Routledge was scheduled to make an appearance in a one-woman show.

Well, it was bucketing down that afternoon, which, had I been metaphorically minded at that spirit-dampening moment, I might have taken as an omen. Not that the rain had the force to keep the crowd, chiefly composed of folks scrambling to make the final check marks on their bucket list, from gathering in the old Tabernacle. Here, the stage was set for Admission: One Shilling. Not much of a stage, mind; there was barely “room for a pony.” Piano, I mean. But little more than that piano was required to transport those assembled to 1940s London, where, for the price of the titular coin, wartime audiences were briefly relieved from the terror of the Blitz by the strains of classical music . . .

The music, back then, was played by British concert pianist Myra Hess who, though much in demand in the United States, put her career on hold to boost the morale of her assailed country(wo)men. Hess did so at the National Gallery, a repository of culture that, at the outbreak of war, had taken on a funereal aspect when its paintings were removed from the walls and carted to Wales to be hidden in caves for the benefit of generations unborn and uncertain.

Meanwhile, those living or on leave in London at the time were confronted with a shrine that held none of the riches worth fighting for but that instead bespoke loss and devastation. From October 1939 to April 1946, Hess filled this ominous placeholder with music; much of it, like her own name, was German—a reminder that the Nazi regime and the likes of Rudolf Hess had no claim to the culture they did not hesitate to extinguish if it could not be made to serve fascist aims.

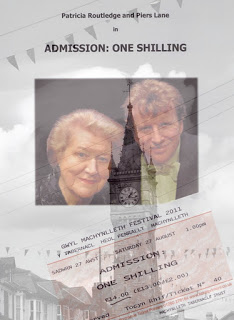

Taking her seat on the stage, the formidable, elegantly accoutred Ms. Routledge seemed well suited to impersonate Dame Myra as a woman looking back at her career in later life. It mattered little that Routledge did not herself play the piano while she reminisced about the concerts she had given. Selections from these performances were played by accompanist Piers Lane, who filled in the musical blanks whenever Routledge paused in her speech.

Writing that speech posed somewhat of a challenge, considering that Hess never published a diary. According to her great nephew, who created this tribute, the script is based on press releases and radio interviews. Indeed, the entire affair comes across as a piece made for radio, if it weren’t for those occasional darts shot at no one in particular from Ms. Routledge’s eyes, frowns that remind you of irritable Ms. Bucket’s priceless double-takes.

Perhaps, it does take a little more—and a little less—to pull off this impression. On the air, we could hear Dame Myra Hess at the piano. If the performance were more carefully rehearsed, or edited, we would not have before our mind’s eye the script from which Routledge reads throughout. We would not require the distractions of a screen onto which photographs of the wartime concerts are projected. We would not be as distanced from the life that yet unfolds in Hess’s own sparse words.

Never mind that Admission: One Shilling has about as much edge as a Laura Ashley throw pillow. What got me is that I felt as if I were attending one of Ms. Bucket’s ill-conceived candlelight suppers, whose decorous make-believe remains ultimately unconvincing. I found myself hoping for something undignified—a pratfall, even—as if I had come to see this woman but not come to see her succeed. Such, I guess, is the lasting legacy, the curse of Hyacinth Bucket that, as I exited, I was wondering what Sheridan might have done with the money . . .