This is a speech I prepared for the private view of “Stanley Anderson: An Abiding Standard” at the Royal Academy of Arts in London on 24 February 2015. Mindful of the assembled party ready to mingle and enjoy the evening, I decided to cut my talk short. Here it is in its entirety.

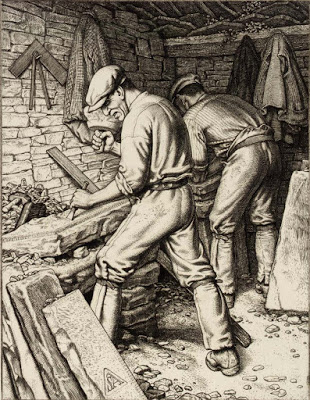

Stanley Anderson’s move from London to Oxfordshire coincides with – and made happen – a body of work for which he is now best known: a series of thirty or so prints on the subject of traditional farming methods and rural trades. They are on view in the Council Room.

Anderson’s move to the countryside was not a retreat. Despite their nostalgic appeal, his works are not escapist. Like his London scenes, they engage with the here and now. His here and now.

Anderson’s prints do not glorify England’s past or gloss over what he perceived to be its problems. It took me a while to appreciate that. As someone interested in the 1930s and 1940s and the impact the Second World War had on civilian life, I was disappointed not to find any overt references to the conflict, any depictions of the homefront, or images of disabled soldiers. After all, Anderson himself lost his London studio during the Blitz.

But they are there, those references. Or at least, Anderson’s commentaries on the human condition are there.

It is telling that so many of the men whose activities – or inactivities – he portrays are old. Anderson himself was in his 50s and 60s when he created these line engravings. The young had gone to war or else were working in the factories. It was war that turned men into machines and that, like other crises before it, had thrown the fragility – or the speciousness – of modern civilization into relief.

Anderson said that, when he moved to the country, his ‘mind and feelings became clearer, more definite in their reactions.’ In the countryside, alive to the seasons, he ‘seemed immersed in a sense of stability’ that was ‘not static. He called it ‘a sort of ordered growth’. Ordered growth in the face of chaos. And what he set out to do in his prints was to remind others of what they were in danger of losing or forgetting: the traditions that, he feared, would die with the men – the friends, neighbours and fellow craftsmen – whose work he commemorated in his prints.

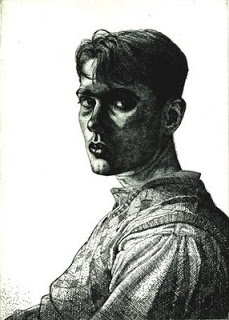

Anderson did not want to be called an “artist.” He did not consider self-expression to be the highest achievement or chief aim of visual culture. He saw himself as a craftsman in the medieval tradition.

He aligned himself with anyone who derived his living – and his satisfaction – from the work produced with his or her own hands, just as Anderson did (with the support of his wife Lilian, a trained nurse).

Trade was not a dirty word for Anderson; nor did he mind getting his hands dirty. He not only related to his working men subjects – menial labourers and skilled craftsmen alike –he befriended these men, at a time when England turned its back on their traditions and forced the hand of many who were pushed into assembly line work or else were made to operate the machinery of war.

Moving to the countryside was not a getting away from mankind but a getting closer to his fellow man. Anderson called fellowship the ‘only currency’ that truly mattered. The ‘pleasure and interest’ of others in his work was what he deemed ‘ample repayment for all [his] labours.’

The hours he spent creating these prints were a time of contemplation; he abhorred speed and distrusted work produced quickly and, he believed, thoughtlessly. His works are spiritual, and the Zeitgeist they capture is that of an age in which spirituality was fast disappearing.

Anderson did not work or live fast. As [co-curator Robert [Meyrick] said, he spent seven years as an apprentice in his father’s engraving workshop, an experience on which he would draw and which he would not regret. His career is a continuum that anyone banking on instant fame might find hard to comprehend. His aim was to live by an abiding standard and his career was the reward of biding his time.

‘My life has been a quiet, studious one,’ the sixty-year-old Stanley Anderson told an American friend who wanted to write a biographical essay on him. There had been ‘no exciting experiences immorally, no amazing lights and shades, no boisterous contretemps; just a steady, sustained effort to express clearly and as well as my ability will allow, that note, in the main, I feel so deeply in life and nature – the plaintive note […].’

‘I often wonder, Anderson added, ‘if this is the reason I crave the friendship of sympathetic folk; why I feel that the arts are a social, or sociable act; why I abhor the bigotry, the insufficiency of self, and fear the exclusiveness of ‘success.’

Before we continue enjoying the ‘sociable act’ of this private view, I would like to express my gratitude to the man to whom everyone seeing this exhibition is indebted: to Stanley Anderson himself.

Anderson reminded me, again and again, how rewarding – how necessary – it is to keep at it, to keep looking, beyond the first glance in the search for novelty or the reassuring instance of recognition.

“In all matters of execution his work is highly disciplined,” a 1932 review in the London Times declared “and, if he seldom thrills you, he never lets you down.” If by thrill we mean the quickening pulse in response to the flashy and sensational, then the reviewer was certainly right. But there are thrills in Anderson’s work that are the rewards of anyone who keeps looking: discoveries of social commentaries – cultural references and sly observations – in which Anderson’s prints are rich.

We have not provided object labels for each of the 90 or so works on display here because we want to encourage you to look for yourselves without being told what to see. Anderson will tell you much about his attitudes toward modernity – and toward modernism – in these prints. These are not works that are open to a myriad of individual interpretations. His intentions become clear, his message, which often appears in fine print – in signs, fictional newspaper headlines and literary allusions – is consistent. His prints are essays on modern life and traditional labour, for the appreciation of which every line counts. So, stay a while …. and keep on looking.

“Stanley Anderson: An Abiding Standard” is on at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from 25 February to 24 May 2015.