As a frustrated writer, or, rather, as someone who is disenchanted with the business of publishing and of ending up not reaching an audience, I have come to embrace exhibition curating as an alternative to churning out words for pages rarely turned. I teach curating for the same reason.

Staging an exhibition reminds students of the purpose of research and writing as an act of communication. Seeing an audience walking into the gallery – or knowing that anyone could stop by and find their research on display – is motivating students and encourages them to value their studies differently.

As someone who teaches art history, and landscape art in particular, to students whose degree is in art practice, curating also enables me to bridge what they might experience as a gap or disconnect between practice and so-called theory, between their lives as artist and art history at large.

It also gives me a chance to make what I do and who I am feel more connected.

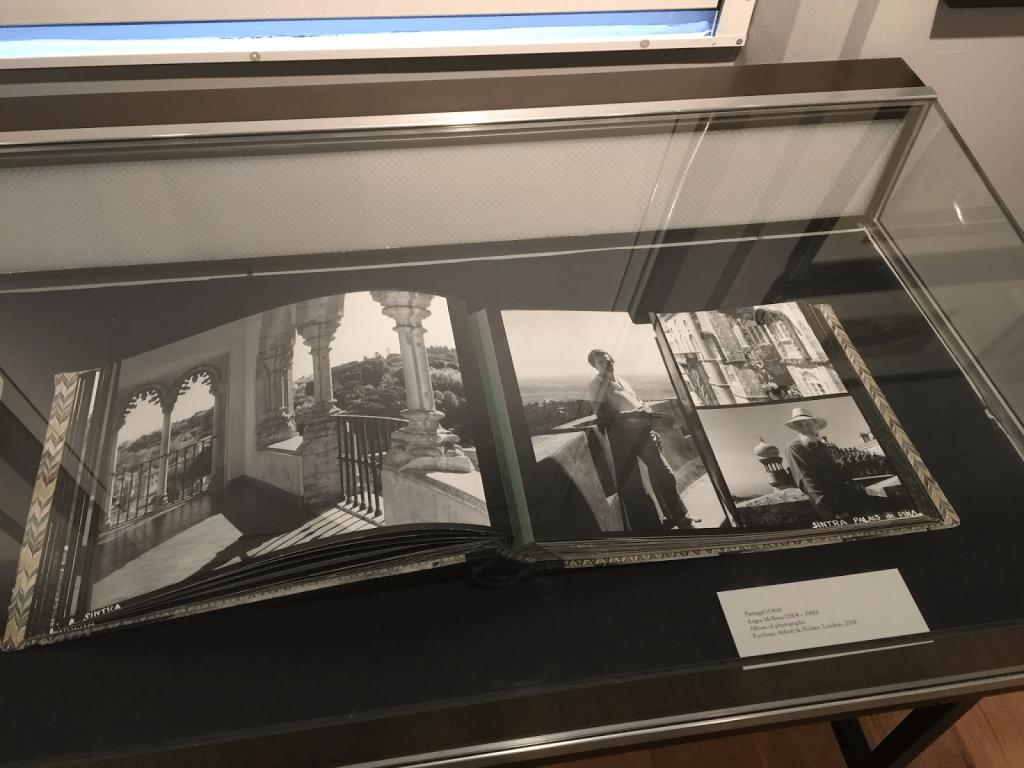

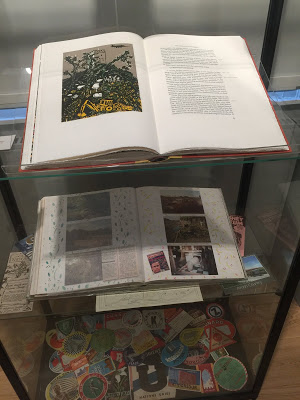

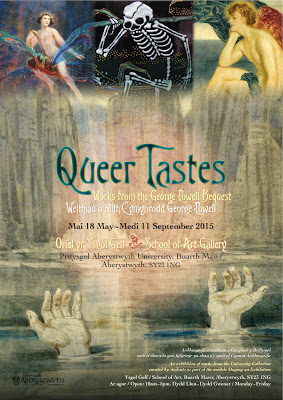

In my latest interactive and evolving exhibition, Travelling Through: Landscapes/Landmarks/Legacies (on show at the School of Art, Aberystwyth University, Wales until 8 February 2019), I bring together landscape paintings, ceramics, fine art prints, travel posters and luggage labels, which are displayed alongside personal photographs, both by a famous photographer (Angus McBean) and by myself.

Here is how I tried to describe the display of those never before publicly displayed images from my personal photo albums:

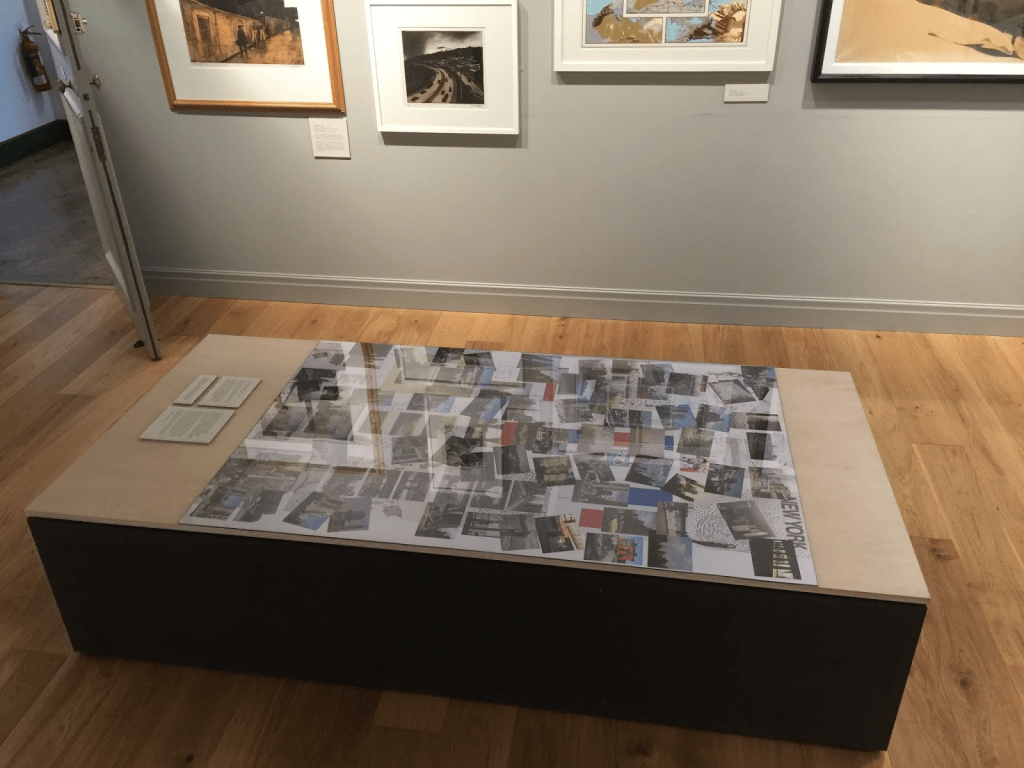

Before the age of digital photography, smart phones and social media, snapshots were generally reserved for special occasions. Travelling was such an occasion.

For this collage, I rummaged through old photo albums and recent digital photographs. When I lived in New York, from 1990 to 2004, I very rarely photographed the city. All of these images either predate that period or were produced after it. The historic event of 11 September 2001 can be inferred from the presence and absence of a single landmark.

The World Trade Center is prominent in many of my early tourist pictures. Now, aware of my gradual estrangement from Manhattan, I tend to capture the vanishing of places I knew.

For this collage, I rummaged through old photo albums and recent digital photographs. When I lived in New York, from 1990 to 2004, I very rarely photographed the city. All of these images either predate that period or were produced after it. The historic event of 11 September 2001 can be inferred from the presence and absence of a single landmark.

The World Trade Center is prominent in many of my early tourist pictures. Now, aware of my gradual estrangement from Manhattan, I tend to capture the vanishing of places I knew.

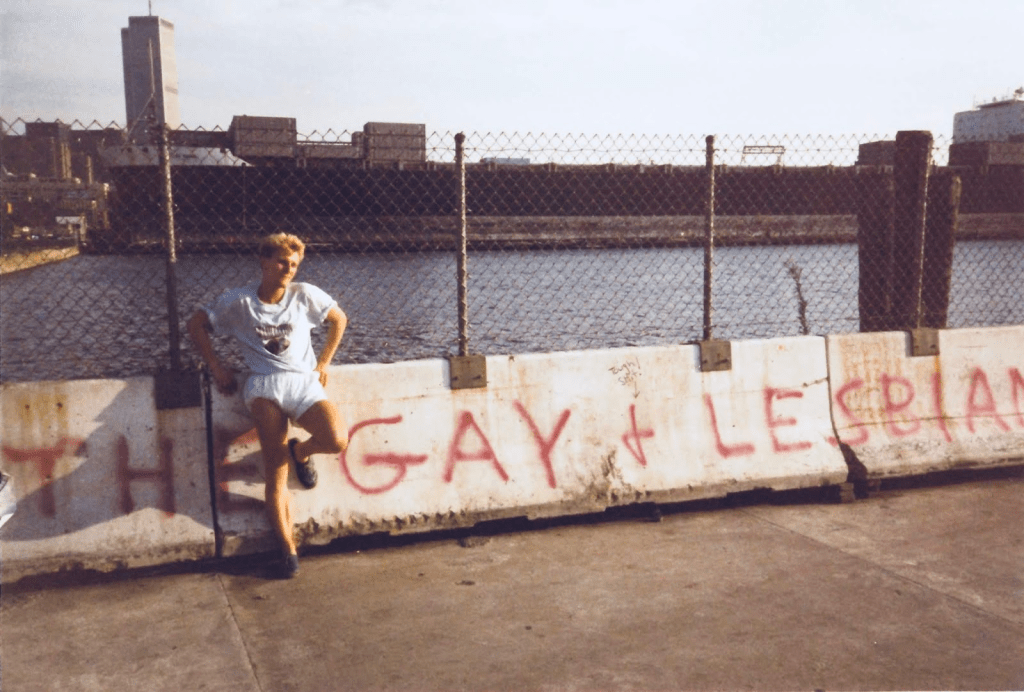

Back in the 1980s, New York was not the glamorous metropolis I expected to find as a tourist. My early photographs reflect this experience. Most are generic views of the cityscape. Others show that I tentatively developed an alternative vision I now call ‘gothic.’ Yet unlike Rigby Graham, whose responses to landscape are displayed elsewhere in this gallery, I could never quite resist the sights so obviously signposted as attractions.

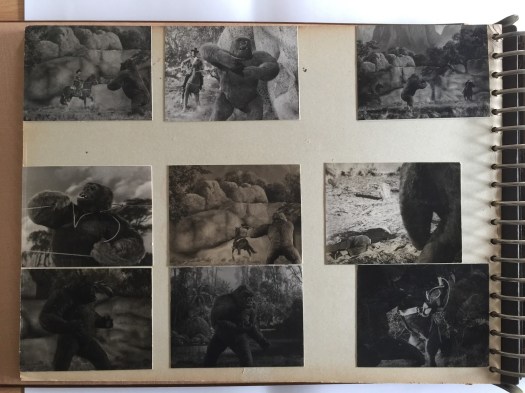

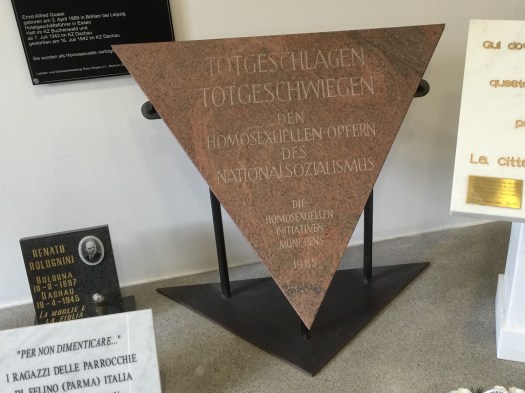

Like the personal photo album of the queer Welsh-born photographer Angus McBean, also on show in this exhibition, these pages were not produced with public display in mind. McBean’s album was made at a time when homosexuality was criminalised. It is a private record of his identity as a gay man.

I came out during my first visit to New York. The comparative freedom I enjoyed and the liberation I experienced were curtailed by anxiety at the height of the AIDS crisis.

Being away from home can be an opportunity to explore our true selves. Travelling back with that knowledge can be long and challenging journey.

Harry Heuser, exhibition curator

Well, I know. You can’t catch cold getting caught in the rain. At least, that’s what people keep telling me straight to my weather-beaten face. Meanwhile, I got soaked during one of those torrential New York City downpours a few night’s ago and was not up to meeting an old friend for dinner last night, notwithstanding the fact that my days in the city are numbered and I might have to wait another year for another opportunity to see him. I ended up watching television instead; it’s something I rarely do nowadays, especially while vacationing.

Well, I know. You can’t catch cold getting caught in the rain. At least, that’s what people keep telling me straight to my weather-beaten face. Meanwhile, I got soaked during one of those torrential New York City downpours a few night’s ago and was not up to meeting an old friend for dinner last night, notwithstanding the fact that my days in the city are numbered and I might have to wait another year for another opportunity to see him. I ended up watching television instead; it’s something I rarely do nowadays, especially while vacationing. I often ask myself whether I am. History, I mean. Not that anyone is opening a museum dedicated to my life, a definitive space for finite time as it is

I often ask myself whether I am. History, I mean. Not that anyone is opening a museum dedicated to my life, a definitive space for finite time as it is  Well, only a few short hours ago I was

Well, only a few short hours ago I was