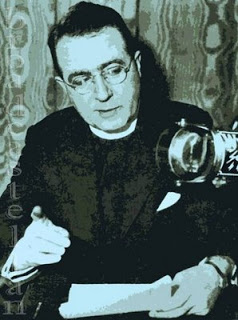

Listeners tuning in to station WHBI, Newark, New Jersey, on this day, 11 December, in 1938, were reminded that what they were about to hear was “in no sense a donated hour.” The broadcast was “paid for at full commercial rates”; and as long as they desired Father Coughlin into their homes, he would be “glad to speak fearlessly and courageously” from the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan, from whence he spread what was billed as a “message of Christianity and Americanism to Catholic and Protestant and religious Jew.”

Listeners tuning in to station WHBI, Newark, New Jersey, on this day, 11 December, in 1938, were reminded that what they were about to hear was “in no sense a donated hour.” The broadcast was “paid for at full commercial rates”; and as long as they desired Father Coughlin into their homes, he would be “glad to speak fearlessly and courageously” from the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan, from whence he spread what was billed as a “message of Christianity and Americanism to Catholic and Protestant and religious Jew.”

As Siegel and Siegel point out in their aforementioned study Radio and the Jews (2007), Father Coughlin was at that time increasingly coming under attack. In the fall of 1938, some stations no longer carried his weekly radio addresses, which had once been heard by as many as forty-five million US Americans. While anxious to defend himself, Coughlin was not about to recant or withdraw.

In his 11 December broadcast, he expounded again on his favorite subject, “persecution and Communism,” by which he meant the persecution of American Christians by Communist Jews. It was his “desire as a non-Jew,” Coughlin insisted, to tell his audience, including “fellow Jewish citizens,” the “truth.”

The adjective “religious,” attached as was by Coughlin only to Jew, not to Catholic or Protestant, was significant in his defense of his special brand of anti-Semitism, a distinction between “good” and “bad” Jews that enabled him to denounce “atheistic Jews” as Communists. “Show me a man who disbelieves in God, and particularly who opposes the dissemination of knowledge concerning God, and I will show you an embryonic Communist.”

In his condemnation of the “insidious serpent” of atheism as manifested in Communism, however, Coughlin made no mention of non-practicing Catholics or non-believing Protestants. According to his preachings, the Jew, rather than the Catholic or Protestant, was that “embryonic” Communist. No other religions got as much as a mention.

Ostensibly to “inform” listeners “what thoughts millions of persons are entertaining,” Coughlin argued that, in “Europe particularly, Jews in great numbers have been identified with the Communist movement, with Communist slaughter and Christian persecution.”

He urged American Jews—the “Godless” among whom were conspiring to do away with “the last vestiges of Christmas practices from our schools”—to disassociate themselves from the Jews in Europe at the very moment in modern history when the Jews in Europe were most in need of support from the free world:

O, there comes a time in the life of every individual as well as in the life of every nation when righteousness and justice must take precedence over the bonds of race and blood. Tolerance then becomes a heinous vice when it tolerates the theology of atheism, the patriotism of internationalism, and the justice of religious persecution.

While “graciously admit[ing] the contribution towards religion and culture accredited to Jews”; while claiming to have spent “many precious hours” in the “companionship of the prophets of Israel,” Coughlin got down at last to the nastiness that was his business. As he put it,

when the house of our civilization is wrapped in the lurid flames of destruction, this is not the time for idle eulogizing. When the house is on fire, its tenants are not apt to gather in the drawing room to be thrilled by its paintings and raptured by its sculpture, its poetry, its tomes of music or its encyclopedia of science, which are there on exhibit. When the house is on fire, as is the house of our civilization today, we dispense with gratifying urbanities and call in the fire department to save our possessions lest they be lost in the general conflagration.

Any acknowledgment that the “conflagration” threatened the Jews more than the Christians so shortly after Kristallnacht—the atrocities of which he gainsaid in his 20 November 1938 broadcast—are relegated to the attic that are the dependent clauses of Father Coughlin’s rhetoric, which, in its far from courageous concessions, is as disingenuous and invidious as the language of Bill O’Reilly today.