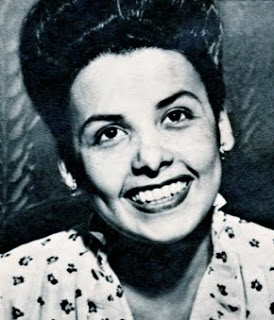

When I heard of the passing of Lena Horne, the words “You Were Wonderful” came immediately to mind. Expressive of enthusiasm and regret, they sound fit for a tribute. However, by placing the emphasis on the first word, we may temper our applause—or the patronising cheers of others—with a note of reproach, implying that while Horne’s performances were marvellous, indeed, the system in which she was stuck and by which her career was stunted during the 1940s was decidedly less so. No simple cheer of mine, “You Were Wonderful” is also the title of a radio thriller that not only gave Horne an opportunity to bring her enchanting voice to the far from color-blind medium of radio but to voice what many disenchanted black listeners were wondering about: Why fight for a victory that, of all Americans, will benefit us least? As title, play, and cheer, “You Were Wonderful”—captures all that is discouraging in those seemingly uncomplicated words of encouragement.

Written by Robert L. Richards, “You Were Wonderful” aired over CBS on 9 November 1944 as part of the Suspense series, many of whose wartime offerings were meant to serve as something other than escapist fare. As I argued in Etherized Victorians, stories about irresponsible Americans redeeming themselves for the cause were broadcast nearly as frequently as plays designed to illustrate the insidiousness of the enemy. Despite victories on all fronts, listeners needed to be convinced that the war was far from over and that the public’s indifference and hubris could endanger the war effort, that both vigilance and dedication were required of even the most war-weary citizen. “You Were Wonderful” played such a role.

When a performer in a third-rate nightclub in Buenos Aires suddenly collapses on stage and dies, a famous American entertainer (Horne) is rather too eager replace her. “I’m a singer, not a sob sister,” she declares icily, thawing for a tantalizing rendition of “Embraceable You.”

The very name of the mysterious substitute, Lorna Dean, encourages listeners to conceive of “You Were Wonderful” in relation to the perennially popular heroine Lorna Doone, or the Victorian melodramatic heritage in general, and to consider the potential affinities between the fictional singer and her impersonatrix, Lena Horne, suggesting the story to be that of an outcast struggling to redeem herself against all odds.

One of the regulars at the nightclub is Johnny (Wally Maher), an seemingly disillusioned American who declares that his country did not do much for him that was worth getting “knocked off for.” Still, he seems patriotic enough to become suspicious of the singer’s motivations, especially after the club falls into the hands of a new manager, an Austrian who requests that his star performer deliver specific tunes at specified times. The absence of a narrator signalling perspective promotes audience detachment, a skeptical listening-in on the two central characters as they question each other while all along compromising themselves.

When questioned about her unquestioning compliance, Lorna Dean replies:

I’m an entertainer because I like it. And because it’s the only way I can make enough money to live halfway like a human being. With money I can do what I want to—more or less. I can live where I want to, go where I want to, be like other people—more or less. Do you know what even that much freedom means to somebody like me, Johnny?

However restrained, such a critique of the civil rights accorded to and realized by African-Americans, uttered by a Negro star of Horne’s magnitude, was uncommonly bold for 1940s radio entertainment, especially considering that Suspense was at that time a commercially sponsored program.

“[W]e are not normally a part of radio drama, except as comedy relief,” Langston Hughes once remarked, reflecting on his own experience in 1940s broadcasting. A comment on this situation, Richards’s writing—as interpreted by Horne—raises the question whether Horne’s outspoken character could truly be the heroine of “You Were Wonderful.”

Talking in the see-if-I-care twang of a 1930s gang moll, Lorna is becoming increasingly suspect, so that the questionable defense of her apparently selfish behavior serves to render her positively un-American. When told that her command performances are shortwaved to a German submarine and contain a hidden code to ready Nazis for an attack on American ships, she claims to have known this all along.

The conclusion of the play discloses the singer’s selfishness to have been an act. Risking her life, Lorna Dean defies instructions and, deliberately switching tunes, proudly performs “America (My Country ‘Tis of Thee)” instead.

About to be shot for her insubordination, Lorna is rescued by the patron who questioned her integrity, a man who now reveals himself to be a US undercover agent. When asked why she embarked upon this perilous one-woman mission, the singer declares: “Just to get in my licks at the master race.”

“You Were Wonderful,” which, like many wartime programs was shortwaved to the troops overseas, could thus be read as a vindication of the entertainment industry, an assurance to the GIs that their efforts had the unwavering support of all Americans, and a reminder to minorities, soldiers and civilians alike, that even a democracy marred by inequality and intolerance was preferable to Aryan rule.

Ever since the Detroit race riots of June 1943, during which police shot and killed seventeen African-Americans, it had become apparent that unconditional servitude from citizens too long disenfranchised could not be taken for granted. With “You Were Wonderful,” Horne was assigned the task of assuring her fellow Negro Americans of a freedom she herself had to wait—and struggle—decades rightfully to enjoy.

Had it not been for this assignment, Lena Horne may never have been given the chance to act in a leading role in one of radio’s most prominent cycles of plays. Yes, “You Were Wonderful,” Lena Horne—and any tribute worthy of you must also be an indictment.