Just what is ‘gothic’? And how useful is the term when loosely applied to products of visual culture, be it paintings, graphic novels, movies or the posters advertising them? Aside from denoting a literary genre and a style of architecture, in which usages I recommend setting it aside by making the ‘g’ upper case, the term ‘gothic,’ understood as a mode, can be demonstrated to take many shapes, transcend styles, media, cultures and periods. It can also be demonstrated not make sense at all as a grab bag for too many contradictory and spurious notions many academics, to this day, would not want to be caught undead espousing. Those are the views I take on and the potentialities I test out with students of my module Gothic Imagination at the School of Art, Aberystwyth University.

As the gothic cannot thrive being crammed into a series of seminars, let alone been exsanguinated or talked to death in academic lectures, I created an extracurricular festival of film screenings to explore the boundaries of the visual gothic beyond genre and style. The fourth film in the chronologically arranged series, Sherlock Holmes Faces Death (1943), demonstrates that the gothic struggles to thrive as well when its sublime powers are expended in a game of wartime chess.

The fourth entry in a series of Universal B-movies that began in 1939, prior to the end of US isolationism, as feature films, Sherlock Holmes Faces Death is a formulaic whodunit in which the gothic is an accessory to crime fiction, and in which suspects, some more usual than others, are lined up like cardboard grotesques for deployment in a mock-Gothic extravaganza executed on a budget.

Now, as a lover of whodunits and epigrams, I do not object to formula or economics. I can appreciate budget-regard even when I long for that rara avis. For the gothic, however, a cocktail consisting in measures equal or otherwise of solvable mystery and final-solution mastery is a cup of hemlock. Granted, the attempt to serve it and make it palatable to the public creates a tension of intentions that may well give motion picture executives and censors nightmares.

I discuss such messaging mixers in the context of radio plays in a chapter of Immaterial Culture I titled “‘Until I know the thing I want to know’: Puzzles and Propaganda,” in which Holmes and Watson also feature.

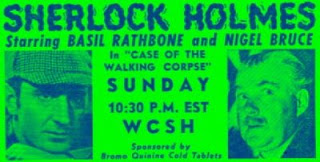

After all, at the same time the pair set the world aright in twentieth-century wartime scenarios, Holmes and Watson continued to solve crime in the gaslit alleyways of late-Victorian and Edwardian London, or suitably caliginous settings elsewhere in the British Isles, in pastiches in which Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce were heard on the New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes radio program that aired in the US at the same time:

As Sherlock Holmes director Glenhall Taylor recalled, the series was one of several sponsored programs whose “services were requested by the War Department.” The charms of an imagined past were to yield to visible demonstrations of the responsibilities broadcasters and audiences shared in the shaping of the future. To promote the sale of defense bonds during the War Loan Drives, Bruce and co-star Basil Rathbone appeared in “special theatrical performances,” live broadcasts to which “admission was gained solely through the purchase of bonds.” (Heuser, Immaterial Culture 189)

To be sure, Sherlock Holmes Faces Death is less overtly propagandist than the previous three entries in Universal’s film series, all of which are anti-fascist spy thrillers. Adapted, albeit freely, from a story by their creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the case they took on subsequently recalled the titular detective and his faithful sidekick from Washington, DC, and released them back into their fog-shrouded habitat in and for which they had been conceived.

And yet, whatever the setting, in motion pictures Holmes and Watson continued to face adversaries that were recognisably anti-democratic – stand-ins for the leaders of the Axis. The villain of Sherlock Holmes Faces Death, diagnosed as egomaniacal by Holmes, is no exception.

Much of the action of Sherlock Holmes Faces Death takes place in an ancestral pile that has been temporarily converted into a convalescent home for wounded soldiers. Those inmates may have their idiosyncrasies, as all flat characters do, but, to serve their purpose in a piece of propaganda, they cannot truly be plotting murder, unless there are exposed as phoneys, in which case the reassurances of wartime service honored and government assistance rendered would be called into question.

The unequivocal messages the Sherlock Holmes films were expected to spread in wartime did not allow for such murky developments. A post-war noir thriller might sink its teeth into corruption; but the Sherlock Holmes series did not exhibit such fangs.

how much Ella Fitzgerald contributed to the success of the film at the box office.

Nor could the recovering soldiers be shown to be so mentally unstable as to kill without motive; according to the convention of whodunits, even serial killers like Christie’s Mr. ABC follow a certain logic that can be ascertained. The heiress of Musgrave Manor may be momentarily distraught, the butler may be exposed as an unstable drunkard – but the soldiers, whatever horrors and shocks they endured on the battlefield, can only be moderately muddled.

Most of the recovering servicemen – in their fear of unwrapped parcels or their fancy for knitting – are called upon to provide comic relief, bathos being a key strategy of the domesticated gothic. In the Sherlock Holmes series, that is a part generally allotted to Dr. Watson, a role he performs even in this particular installment, in which his expertise as a man of medicine is put to use for the war effort. Inspector Lestrade serves a similar purpose, which is probably what made the ridiculing of military personnel seem less objectionable to sponsors, as it made them look fairly inconsequential to the crime caper unfolding. Aligning those men with Watson and Lestrade assists in eliminating them from the start as potential suspects.

While missing legal documents and cryptic messages are certifiably Gothic tropes, the gothic atmosphere in Sherlock Holmes Faces Death is fairly grafted on the proceedings with the aid of visuals. There are genre Gothic trimmings aplenty in – secret passages, a bolt of lightning striking a hollow suit of armor, and pet raven assuming the role of harbinger of death – but there is no real sense of menace as, guided by the infallibly capable hands of Sherlock Holmes, we negotiate with relative ease the potentially treacherous territory of a mansion as makeshift asylum and contested castle.

The climax, which tries to cast doubt as to Holmes’s perspicacity, plays out in a dimly lit cellar. It is here that the gothic could potentially take hold if the plot had not preemptively diffused the dangerous situation hinted at in the film’s title. The trap for the killer below has already been laid above-ground on the newly polished surface of a giant chessboard, in a display of strategy choreographed by Holmes himself. By the time the game moves underground, it is no longer afoot; rather, it is fairly limping along.

Gothic and propaganda can mix; genre Gothic fiction often served political purposes. Gothic and whodunit are less readily reconciled. Although John Dickson Carr tried hard to make that happen, often in an antiquarian sort of way, the Victorian Sensation novelists and the had-I-but-known school of crime writers come closer to achieving that. But the handling of all three of those form or raisons d’être for writing – Gothic, whodunit and propaganda – by the jugglers employed here, at least, is not a formula designed to make the most of mystery and suspense. As I concluded in my discussion of the “identity crisis” of the wartime radio thriller, “propagandist work was complicated by the challenge of puzzling and prompting the audience, of distracting and instructing at once.”

Sherlock Holmes faces death, all right, but the demise he encounters is that of the gothic spirit.

Well, I am not sure which state of oblivion is more tolerable: to forget or to be forgotten. I tend to commute between the two, as most folks do. Yet I am far more troubled by the defects of my own memory than by any failure on my part to leave an indelible imprint of me on the minds of others. The latter might injure my pride from time to time; but the former damages the very core of my self as a being in space and time. Is this why I am attracted to pop-cultural ephemera, to the once famous and half forgotten, to the fading sounds of radio and the passing fame of its personalities? Am I, by trying to keep up with the out-of-date, rehearsing my own struggle of keeping anything in mind and preventing it from fading?

Well, I am not sure which state of oblivion is more tolerable: to forget or to be forgotten. I tend to commute between the two, as most folks do. Yet I am far more troubled by the defects of my own memory than by any failure on my part to leave an indelible imprint of me on the minds of others. The latter might injure my pride from time to time; but the former damages the very core of my self as a being in space and time. Is this why I am attracted to pop-cultural ephemera, to the once famous and half forgotten, to the fading sounds of radio and the passing fame of its personalities? Am I, by trying to keep up with the out-of-date, rehearsing my own struggle of keeping anything in mind and preventing it from fading?