Jumping Jehosophat! It sure feels good to rant about our elected government—some force that, at times, appears to us (or is conveniently conceived of) as an entity we don’t have much to do with, after the fact or fiction of election, besides the imposition of carrying the burden of enduring it, albeit not without whingeing. Back on this day, 4 May, in 1941, the Columbia Broadcasting System allotted time to remind listeners of the Free Company just what it means to have such a right—the liberty to voice one’s views, the “freedom from police persecution.” The play was “Above Suspicion.” The dramatist was to be the renowned author Sherwood Anderson, who had died a few weeks before completing the script. In lieu of the finished work, The Free Company, for its tenth and final broadcast, presented its version of “Above Suspicion” as a tribute to the author.

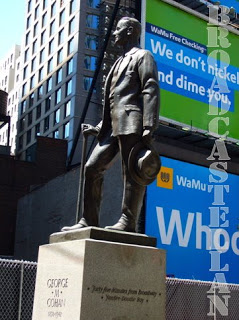

Starred on the program, in one of his rare radio broadcasts—and perhaps his only dramatic role on the air—was the legendary George M. Cohan (whose statue in Times Square, New York City, and tomb in Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx, are pictured here). Cohan, who had portrayed Franklin D. Roosevelt in I’d Rather Be Right was playing a character who fondly recalls Grover Cleveland’s second term, but is more to the right when it comes to big government.

The Free Company’s didactic play, set in New York City in the mid-1930s, deals with a complicated family reunion as the German-American wife of one Joe Smith (Cohan) welcomes her teenage nephew, Fritz (natch!), from the old country. Fritz’s American cousin, for one, is excited about the visit. Trudy tells as much to Mary, the young woman her mother hired to prepare for the big day:

Trudy. Mary, I have a cousin.

MARY. Yeah, I know, this Fritz.

TRUDY. Have you a cousin?

MARY. Sure, ten of ‘em.

TRUDY. What are they like?

MARY. All kinds. One’s a bank cashier and one’s in jail.

TRUDY. In jail! What did he do?

MARY. He was a bank cashier, too [. . .].

Make that “executive” and it almost sounds contemporary. In “Above Suspicion,” the American characters are not exactly what the title suggests. That is, they aren’t perfect; yet they are not about to conceal either their past or their positions.

Trudy’s father is critical of the government, much to the perturbation of Fritz, who has been conditioned to obey the State unconditionally:

SMITH. Jumping Jehosophat [chuckles]. Listen, the State’s got nothing to do with folks’s private affairs. Nothing.

FRITZ. Please, Uncle Joe, with all respect. If the State doesn’t control private affairs, how can the State become strong?

SMITH. Oh, it will become strong, all right. You know, sorry, it might become too darn strong, I’ll say. And I also say, let the government mind its own dod-blasted business and I’ll mind mine.

To Fritz, such “radical” talk is “dangerous”; after all, his education is limited to “English, running in gas masks, and the history of [his] country.” He assumes that Mary is a spy and that anyone around him is at risk of persecution. To that, his uncle replies: “Dangerous? Well, I wish it was. The trouble is, nobody pays any attention. By gad, all I hope is that the people wake up before the country is stolen right out from under us, that’s what I hope.”

“Above Suspicion” is a fairly naïve celebration of civil liberties threatened by the ascent of a foreign, hostile nation (rather than by forces from within). Still, it is a worthwhile reminder of what is at stake today. Now that the technology is in place to eavesdrop on private conversations (the British government, most aggressive among the so-called free nations when it comes to spying on the electorate, is set to monitor all online exchanges), we can least afford to be complaisant about any change of government that would exploit the uses of such data to suppress the individual.

“Dictaphones,” Smith laughs off Fritz’s persecution anxieties.

I wish they would some of those dictaphones here. I’d pay all the expenses to have the records sent right straight to the White House. That’s what I’d do. Then they’d know what was going on then. [laughs] They’d get some results then, hey, momma?

These days, no one is “Above Suspicion.” Just don’t blame it on Fritz.