“What is there to say about what one loves except: I love it, and to keep on saying it?” Roland Barthes famously remarked. Sometimes, getting to the stage of saying even that much requires quite a bit of effort; and sometimes you don’t get to say it at all. Love may be where you find it, but it may also be the very act of discovery. The objective rather than the object. The pursuit whose outcome is uncertain. Methodical, systematic, diligent. Sure, research, if it is to bear fruit, should be all that. And yet, it is also a labor of love. It can be ill timed and unappreciated. If nothing comes of it, you might call it unrequited. It may be all-consuming, impolitic and quixotic. Still, it’s a quest. It’s passion, for the love of Mike!

“Mike” has been given me a tough time. It all began as a wildly improbable romance acted out by my favorite leading lady. It was nearly a decade ago, in the late spring of 2001, that I first encountered the name. “Mike” is a reference in the opening credits of the film Torch Singer, a 1933 melodrama starring Claudette Colbert. Having long been an admirer of Ms. Colbert—who, incidentally made her screen debut in the 1927 comedy For the Love of Mike, a silent film now lost—I was anxious to catch up with another one of her lesser-known efforts when it was screened at New York City’s Film Forum, an art house cinema I love for its retrospectives of classic—and not quite so classic—Hollywood fare.

Until its release on DVD in 2009, Alexander Hall’s Torch Singer was pretty much a forgotten film, one of those fascinatingly irregular products of the Pre-Code era, films that strike us, in the Code-mindedness with which we are conditioned to approach old movies, as being about as incongruous, discomfiting and politically incorrect as a blackface routine at a Nelson Mandela tribute or a pecan pie eating contest at a Weight Watchers meeting. Many of these talkies, shot between 1929 and 1934, survive only in heavily censored copies, at times re-cut and refitted with what we now understand to be traditional Hollywood endings.

Torch Singer, which tells the Depression era story of a fallen woman who takes over a children’s program and, through it, reestablishes contact with the illegitimate daughter she could not support without falling, has, apart from its scandalous subject matter, such an irresistible radio angle that I was anxious to discuss it in Etherized Victorians, the dissertation on American radio drama I was then in the process of researching.

Intent on presenting radio drama as a literary rather than historical or pop-cultural subject, I was particularly interested in published scripts, articles by noted writers with a past in broadcasting, and fictions documenting the central role the “Enormous Radio” played in American culture during the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s. I thought about dedicating a chapter of my study to stories in which studios serve as settings, microphones feature as characters, and broadcasts are integral to the plot.

Torch Singer is just such a story—and, as the opening credits told me, one with a past in print. Written by Lenore Coffee and Lynn Starling, the screenplay is based on the story “Mike” by Grace Perkins; but that was all I had to go on when I began my search. No publisher, no date, no clues at all about the print source in which “Mike” first came before the public.

Little could be gleaned from Perkins’s New York Times obituary—somewhat overshadowed by the announcement of the death of Enrico Caruso’s wife Dorothy—other than that she died not long after assisting Madame Chiang Kai-shek in writing The Sure Victory (1955); that she had married Fulton Oursler, senior editor of Reader’s Digest and author of the radio serial The Greatest Story Ever Told; and that she had penned a number of novels published serially in popular magazines of the 1930s. That sure complicated matters as I went on to turn the yellowed pages of many once popular journals of the period in hopes of coming across the elusive “Mike.”

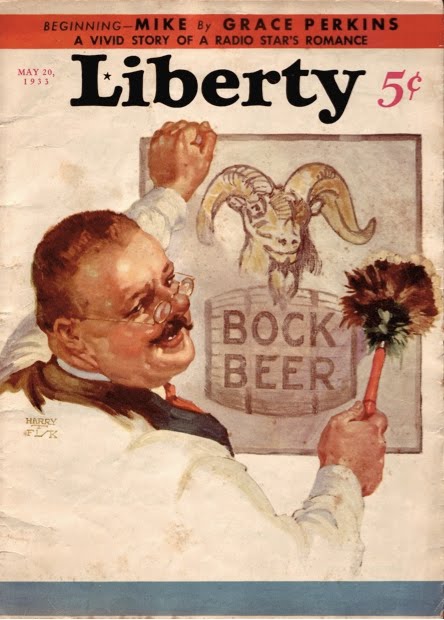

Finally, years after my degree was in the bag—and what a deep receptacle that turned out to be—I found “Mike” between the pages of the 20 May 1933 issue of Liberty; or the better half of “Mike,” at least, as this is a serialized narrative. Never mind; I am not that interested anyway in the story’s other Mike, the man who deserted our heroine and with whom she is reunited in the end. At last, I got my hands on this “Revealing Story of a Radio Star’s Romance,” the story of the “notorious Mimi Benton,” a hard-drinking mantrap who’d likely “end up in the gutter,” but went on the air instead—and “right into your homes! Yes, sir, and talked to your children time and time again!”

“Mike,” like Torch Singer, is a fiction that speaks to Depression-weary Americans who, dependent on handouts, bereft of status and influence, came to realize—and romanticize—what else they lost in the Roaring Twenties when the wireless, initially a means of point-to-point communication, became a medium that, as I put it in my dissertation,

not merely controlled but prevented discourse. Instead of interacting with one another, Depression-era Americans were just sitting around in the parlor, John Dos Passos observed, “listening drowsily to disconnected voices, stale scraps of last year’s jazz, unfinished litanies advertising unnamed products that dribble senselessly from the radio,” only to become receptive to President Roosevelt’s deceptively communal “youandme” from the fireside.

Rather than “listening drowsily,” disenfranchised Mimi Benton, anathema to corporate sponsors, reclaims the medium by claiming the microphone for her own quest and, with it, seizes the opportunity to restore an intimate bond that society forced her to sever. These days, Mimi Benton would probably start a campaign on Facebook or blog her heart out—unless she chose to lose herself in virtual realities or clutch a Tamagotchi, giving up a quest in which the medium can only be a means, not an end.

Related writings

“Radio at the Movies: Torch Singer (1933)”

“Radio at the Movies: Manslaughter (1922)”