“Look, sonny, we’re up here for work. We’ve put this attic off, and put this attic off. Now that we’re here, let’s make every minute count.” That was the voice of reason Rush Gook—and several million radio listeners besides—heard on the day (18 August 1942, to be precise) that mom Sade decided it was time to tackle that stuffy space under the roof of the “small house half-way up in the next block.”

As anyone familiar with Paul Rhymer’s Vic and Sade could guess right off, there was more room for doubt than reason that the task would be accomplished, and that, when the brief visit with the home folks was over, said space would be any more disorganized than it was before the job got underway. You could expect more order, method and sanity sticking your head into Fibber McGee’s closet.

Now, I’m not being etymologically sound here, but it is probably no coincidence that attics are just a single consonant removed from antics—and that is just what you should expect to find while up there, even if it is antiques you’re after.

Our new old house has not one but two attic spaces—and in the smaller of these we found ourselves confronted with some kind of time capsule. Only, it wasn’t quite the right time.

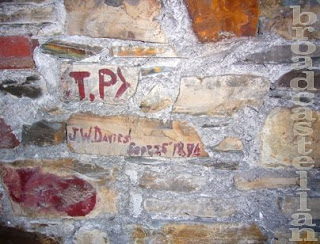

The graffiti on the wall suggests that construction was pretty much completed by September 1896, which was probably the last time the roof space was clutter free. Not that I want it to be barren of memories, mind.

Given the age of the house, I was kind of hoping for a family skeleton. Romantic novels of the Victorian age suggest that the darkest secrets are best kept just below the roof, rather than being crammed into the proverbial closet. Jane Eyre’s Bertha Mason comes to mind, and that seminal study on the subject (Gilbert and Gubar’s Madwoman in the Attic).

Instead, we were treated to “Benny Hill Sings ‘Ernie, the Fastest Milkman in the West.’” Not exactly a Victorian treasure—but at least Ernie’s story has the proper romantic ingredients: lust, rivalry, and premature death (a “stale pork pie caught him in the eye and Ernie bit the dust”); there is even revenge from the beyond, as the milkman’s “evil-looking” successor, Two-Ton Ted from Teddington, is denied the pleasures of his wedding night:

Was that the trees a-rustling? Or the hinges of the gate? / Or Ernie’s ghostly gold tops a-rattling in their crate?

The cleanup sure slowed down once I came across that discarded collection of vinyl, the highlight of which, to me, is a curiosity labeled “Memories of Steam.” The locomotives on the cover could not deceive anyone into expecting the tell-all record of an inveterate Lothario; but I was thrilled nonetheless, transported back to the days when, as a boy, I was given an album of collected noises that led me to stage my own audio dramas—signifying nothing to anyone else, but chock-full of sound and fury. Come to think of it, that one record may well have laid the tracks that, long and winding though they were, earned me a doctorate . . . just the kind of certificate to relegate to the space I had just visited.

Yep, even a climb up to an attic filled with the leavings of previous inhabitants leads me no further than some dim corners of my own memory. Unlike Sade and Rush, I do not have to wait for crazy Uncle Fletcher to disrupt the tasks at hand with one of his dubious recollections (“Sadie, do you remember Irma Flo Kessy there in Belvidere?” She was a “peevish woman” who “used to have a little habit of slappin’ her husband’s face in public”). I can count on my own past to traipse close behind and creep up on me.

This time, though, the detour into those mental crevices was a welcome and trouble-free one. Down below, rooms hung with ghastly wallpaper were waiting for a hand attached to my aching body . . .

Related recordings

“Cleaning the Attic,” Vic and Sade (18 August 1942)

Related writings

“The Home Folks Are Moving In”

“Home Folks Lose Ground to Plot Developers”

Well, this will sound like a familiar story. A small house (halfway up in the next block, say) is being torn down after its long-established and well-liked owners cave in to some corporate big shots who want to get their hands on a valuable piece of property that seems just ripe for redevelopment. The transformation achieved proves agreeable enough to all; but to those who remember the neighborhood and used to stop by at the old house, there is something missing in the bright new complex that has taken its place.

Well, this will sound like a familiar story. A small house (halfway up in the next block, say) is being torn down after its long-established and well-liked owners cave in to some corporate big shots who want to get their hands on a valuable piece of property that seems just ripe for redevelopment. The transformation achieved proves agreeable enough to all; but to those who remember the neighborhood and used to stop by at the old house, there is something missing in the bright new complex that has taken its place. Well, sir, it’s a few minutes or so past six o’clock in the evening as our scene opens now, and here in the garden of the small house halfway up in the Welsh hills we discover Dr. Harry Heuser setting the table for a barbecue dinner. Sorting the flatware, he still keeps an eye on Montague, his Jack Russell terrier. Meanwhile, the side dishes are being prepared in the kitchen and the telephone is ringing. Listen.

Well, sir, it’s a few minutes or so past six o’clock in the evening as our scene opens now, and here in the garden of the small house halfway up in the Welsh hills we discover Dr. Harry Heuser setting the table for a barbecue dinner. Sorting the flatware, he still keeps an eye on Montague, his Jack Russell terrier. Meanwhile, the side dishes are being prepared in the kitchen and the telephone is ringing. Listen. Well, I can’t say that I have been, lately. Well, I mean. My digestive system is on the fritz, and my mood is verging on the dyspeptic. So, if I am to begin this entry in the broadcastellan journal with “Well”—as I have so often done these past six or seven months—it must be a brusque and slightly contentious one, for once. My jovial, welcoming “Well,” by the way, was inspired by Paul Rhymer’s Vic and Sade, a long-running radio series whose listeners were greeted by an announcer who, as if opening the door to the imaginary home of the Gook family, ushered in each of Rhymer’s dialogues with expositions like this one:

Well, I can’t say that I have been, lately. Well, I mean. My digestive system is on the fritz, and my mood is verging on the dyspeptic. So, if I am to begin this entry in the broadcastellan journal with “Well”—as I have so often done these past six or seven months—it must be a brusque and slightly contentious one, for once. My jovial, welcoming “Well,” by the way, was inspired by Paul Rhymer’s Vic and Sade, a long-running radio series whose listeners were greeted by an announcer who, as if opening the door to the imaginary home of the Gook family, ushered in each of Rhymer’s dialogues with expositions like this one: