Inhale. Exhale. Inhale. Exhale. I must try that some time without using a brown paper bag. Just kidding – but only just. It’s been a breathless few weeks. Now that I am coming up for air, I’d like to say, if it were not such a hackneyed phrase, that I have returned from my long and long-delayed New York trip with a suitcase full of memories. Not that I care to be reminded about my luggage, given that, owing to an absent-mindedness brought on by physical exhaustion and an acute state of all-over-the-placeness, my carry-on case continued its journey by rail without me.

Argh. Among other things, the valise gone astray contained a rare copy of Mr. Fortune Finds a Pig (1943), a curiosity of a mystery about which, had I not, through my negligence, forfeited the opportunity of its perusal, I would have liked to say considerably more here, especially given that its story is set in Wales, whereto its English author, H. C. Bailey (1878–1961) retired at the end of his career.

While in New York, I did a bit of research at the New York Public Library’s Billy Rose Theatre Division on lost recordings of Bailey’s “Mr. Fortune” stories, nineteen of which were adapted for US radio in the mid-1930s and are extant as scripts. More about that, and the pig, some other time, the lost-and-found department of Transport for Wales permitting. Never mind flying. Pigs might travel by rail.

Pardon the rustling of mental notes; but as recounted here previously, fortune did not exactly smile on me during my stay in New York, entirely overshadowed as it was, at least initially, by my former partner’s heart attack and my bout of Covid, which barred me from the ICU and turned my legs to lead as I dragged myself from one testing site to another.

Rasp. Not that my sojourns in the metropolis are ever an unalloyed joy, tinged as they invariably are with a sense of loss and estrangement. Each year, the city I knew most closely when I lived there from 1990 to 2004, is becoming less familiar, less recognizable, and generally less worth revisiting, especially since what was particular and once characteristic is gradually being replaced by the generic and corporate.

The pandemic has speeded up this process, with many of the remaining one-of-a-kind sites going under in a sump of sameness. A few years ago, when I researched the career of the English printmaker Stanley Anderson for a catalogue raisonné and a series of exhibitions, I was struck by the sense of dislocation some of his etchings communicate. A kindred spirit, I am alive to Anderson’s visual commentaries on a world that was vanishing – or was made to disappear – before his very eyes.

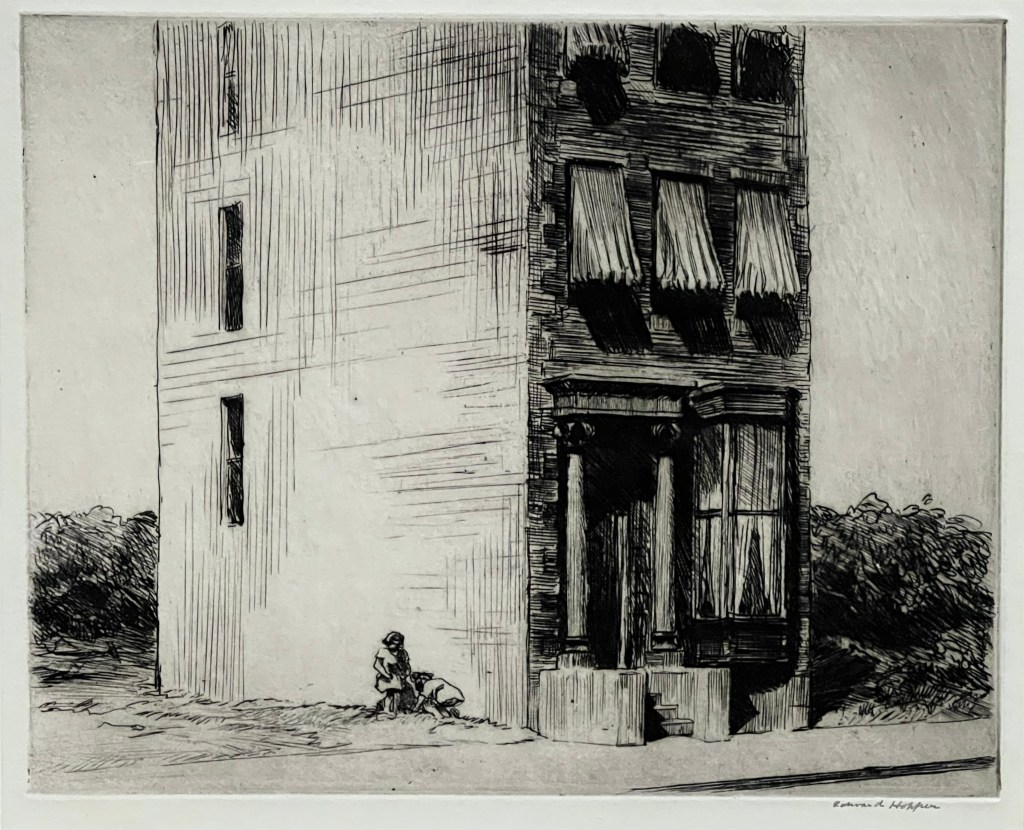

I was reminded of Anderson’s alternative views of 1920s London – of construction sites and demolitions – when I came across the etching The Lonely House (1920) in the exhibition Edward Hopper’s New York at the Whitney. New York City, as the show’s curators put it with platitudinous generality, “underwent tremendous development” during Hopper’s lifetime; and instead of focussing his attention on landmarks that are more likely to stay in place than the architecturally commonplace – an assumption proven false decades later by the pulverization of the World Trade Center, an act of religious fanaticism bringing home that iconoclasm on any scale demands the iconic – Hopper “turned his attention” to “unsung utilitarian structures” and was “drawn to the collisions of the new and old” that “captured the paradoxes of the changing city.”

I am likewise eschewing the presumably picture-worthy sites in Asphalt Expressionism, my upcoming exhibition of large format, printed iPhone photographs of New York City sidewalks that, in a tourist’s pursuit of views or selfie backdrops, tend literally to fall by the wayside despite being in plain sight.

However, it is not visuals alone that vanish or material culture only that is subject to erasure. Sounds, too, face neglect and extinction. Unless they are voices or musical compositions, aural environments are largely unheard of in most records of our experiences, public or private. Sounds may survive as a backing track to our home videos, but rarely do they become the main event, the real thing of our conscious engagement with sensed reality.

Continue reading “ASMR Jungle: Rambling Notes on NYC Composed Out of Earshot”

Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”

Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”