When, at the 2026 World Economic Forum in Davos, the forty-seventh and perhaps last elected President of the United States, in one of his characteristic falsehood-and-insult-littered tirades, referred to Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark he had long coveted, as “a piece of ice,” his imperialism, imperiousness and imperviousness to historical facts were once again on blindingly stark display.

Greenland, Iceland, or whatever the misleader of the fabled free world may call the largest island of them all—if indeed it is land, or a land, rather than a frozen asset on the verge of liquidation—it needed to be his, outright. Until, that is, Number 47 (previously 45 but never adding up to more than number two) was duped into settling for cubes portioned out in a deal existing since 1951. Put that in your Diet Coke and drink it, sucker!

“A piece of ice.” Is not Melania enough? Well, not according to the Epstein files, if ever we get to see them entire and unredacted. The likely scenario of hell freezing over comes to mind, boggled though it is.

“A piece of ice.” That, clearly, is what cultures and communities—history and humanity—are to a rapacious tyke-oon, a petulant plutocrat whose crude, rudimentary vocabulary and short attention span remind us daily how limited his definition of “great” is and how precisely that limitation sums up the narrow mind of a bottom feeder—a Moron-roe Doctrinaire?—raised, none too loftily, on the notion that anyone aspiring to be a big fish needs to swallow whatever comes or gets into his way.

Greatness, thus conceived, means little more than to amass much to amount to more in the eyes of the world he, in a less-than-popular deviation from his America First agenda, has set his greedy peepers on.

“A piece of ice,” indeed! The word is chilling enough as an acronym, when it refers to a deadly experiment in cryotherapy involving the deep-freezing of democracy until it falls off the body politic as if it were an unwelcome and unsightly growth.

While I could not gauge the degree of ire among the largely undemonstrative audience at Davos, the phrase certainly made my blood boil, as does pretty much every exhausting waste of air emanating from a hothead whose actions are raising the global temperature as perilously as the actual warming his administration has chosen to deny for the opportunity of raking in a final few billions. When Number 47 talks Greenland, you can bet he means greenbacks.

It is undeniably global warming that makes the island of Kalaallit Nunaat more strategic a region than it ever was, now that melting ice caps open routes and facilitate access to the Arctic.

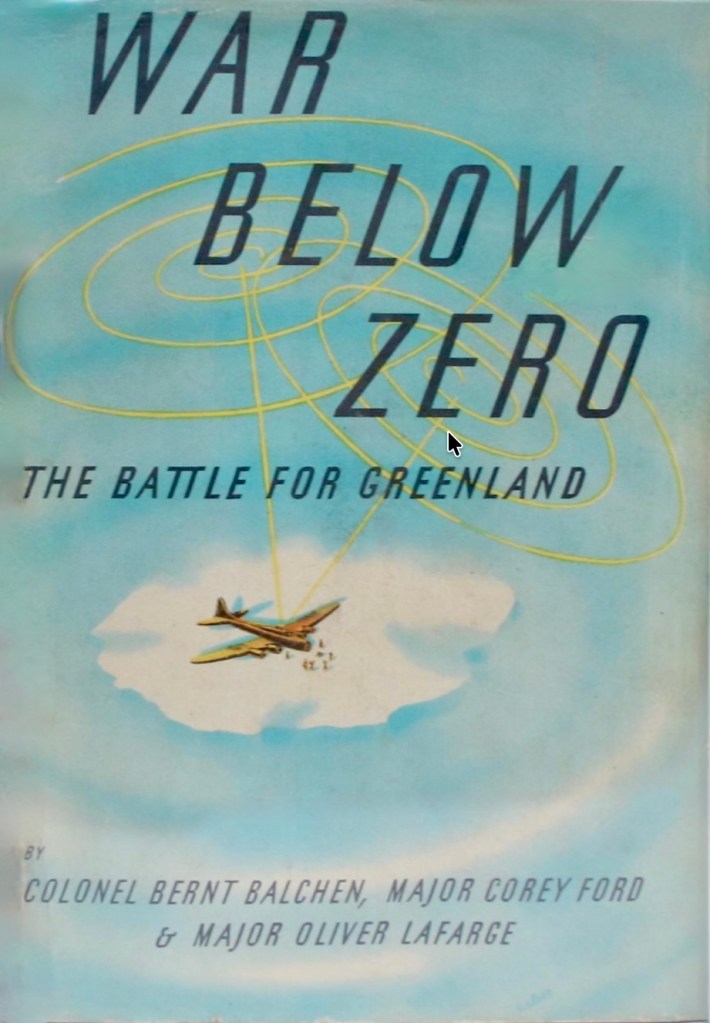

Climate change was not yet an issue during the so-called “Battle for Greenland”—the subtitle and subject of War Below Zero, a book published in 1944. And yet, atmospheric conditions and the ability to forecast them on location were apparently key to the US interest in the region in a pre-satellite age.

According to War Below Zero, the conflict in question was not a war for “territory” but “a war for weather.”

Continue reading ““A piece of ice”: Greenland, a US Mission, and the Drafting of Another War Below Zero”

It is the fuel that keeps the search engines humming. It is fodder for loudmouthed if often unintelligible webjournalists thriving on the divisive. It is the foundation of many a rashly erected platform by means of which the invisible make a display of themselves. The so-called war on terror, I mean, and the time, the shape, and the lives it is taking in Iraq. My position becomes sufficiently clear in those words, as tenuous as it sometimes seems to myself. Experiencing the uncertainty, the turmoil and sorrow that was New York City during the days following the destruction of the World Trade Center, I was anxious to see prevented what then felt like an out and out war against the democratic West; but as a descendant of Nazi sympathizers who is convinced that putting an end to thralldom is a noble cause and conflicted about the use of military force to achieve this end, I could only work myself up to a restrained fervor, which soon gave way to bewilderment, anger, and frustration.

It is the fuel that keeps the search engines humming. It is fodder for loudmouthed if often unintelligible webjournalists thriving on the divisive. It is the foundation of many a rashly erected platform by means of which the invisible make a display of themselves. The so-called war on terror, I mean, and the time, the shape, and the lives it is taking in Iraq. My position becomes sufficiently clear in those words, as tenuous as it sometimes seems to myself. Experiencing the uncertainty, the turmoil and sorrow that was New York City during the days following the destruction of the World Trade Center, I was anxious to see prevented what then felt like an out and out war against the democratic West; but as a descendant of Nazi sympathizers who is convinced that putting an end to thralldom is a noble cause and conflicted about the use of military force to achieve this end, I could only work myself up to a restrained fervor, which soon gave way to bewilderment, anger, and frustration. Feeling as miserable as I do right now (the aforementioned cold), I was tempted to abandon the “On This Day” feature and escape the self-imposed strictures of such a format. Then I came across a recording of Words at War that made me decide not to disenthrall myself just yet. I might not have gotten to know Jean Helion, had it not been for the frustrating and inept adaptation of his wartime memoir They Shall Not Have Me, first broadcast on 23 September 1943.

Feeling as miserable as I do right now (the aforementioned cold), I was tempted to abandon the “On This Day” feature and escape the self-imposed strictures of such a format. Then I came across a recording of Words at War that made me decide not to disenthrall myself just yet. I might not have gotten to know Jean Helion, had it not been for the frustrating and inept adaptation of his wartime memoir They Shall Not Have Me, first broadcast on 23 September 1943.