If I’ve been keeping my trap shut lately, it’s on account of some festering crumbs in my cake hole. Sure, I can jaw away about most anything, but I’ve got to have the mind and the mandible to do so. For days now I have been plagued by mouth ulcers that are putting a muzzle on my spirits—not the kind of oral culture I generally engage with in this journal. My gums are following economic trends, making me feel ever longer in the tooth. My left cheek, in turn, might lead you to believe that, in an effort to dodge the downturn, I managed to squirrel something away for a day on which I may mercifully hide my mug under an umbrella. Meanwhile, my taste buds have started to sprout and my lower lip, Angelina Jolied out of all proportions, is suggestive of a law suitable botch or a risk taken by the likes of Maxie Rosenbloom.

If I’ve been keeping my trap shut lately, it’s on account of some festering crumbs in my cake hole. Sure, I can jaw away about most anything, but I’ve got to have the mind and the mandible to do so. For days now I have been plagued by mouth ulcers that are putting a muzzle on my spirits—not the kind of oral culture I generally engage with in this journal. My gums are following economic trends, making me feel ever longer in the tooth. My left cheek, in turn, might lead you to believe that, in an effort to dodge the downturn, I managed to squirrel something away for a day on which I may mercifully hide my mug under an umbrella. Meanwhile, my taste buds have started to sprout and my lower lip, Angelina Jolied out of all proportions, is suggestive of a law suitable botch or a risk taken by the likes of Maxie Rosenbloom.

Always one to self-diagnose and over-the-counter medicate rather than to seek the professional opinion of someone who, like a satirist with a stethoscope, makes a career out of scrutinizing us at our most unsightly, I have been pondering my condition and its causes. Though I cannot rule out trauma resulting from vigorous brushing recently recommended by my hygienist, I am not inclined to blame my current state on the stress produced by our impending move; if I were quite so readily distressed, I would hardly have survived my previous transplantations. Besides, I have always resented being thought of as a mere tangle of nerves in need of careful rewiring.

I have a long history of allergies, though; and given that my symptoms began to occur following a dinner outing last week, it might well be that my sores are a reaction to something passing my lips that night. Heretofore, my catalogue of allergens has been limited to felines, grass, and dust. Now, that hasn’t kept me from cat-sitting, of which you can make a career in New York City, or from relocating to one of the grassiest spots on the planet; and it certainly did little to convince me to take out the feather duster more often than the snot rag or the inhaler.

I was told early on by the still extant half of the temporary connubial unit responsible for my coming into being—and for getting the heck away from whence I hail—that allergies are an aberrant mental state and that cycling to school through the cornfields or mowing the lawn were activities I could handle if I only put my mind to it. True, I have always been mildly allergic to physical labor; but that was in part due to the damage I saw it inflict on the body, the mind, and the spirit.

My father’s religion was social Darwinism, in the practicing of which he drank himself to death. It would have been futile to convince him that an undistilled grain could be as lethal as a distilled one and that what doesn’t kill you instantaneously does not necessarily make you any stronger in the long run.

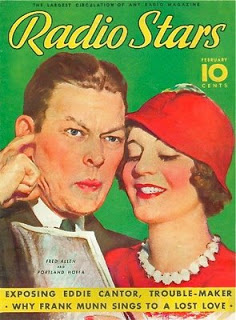

I had not planned on delving into my personal history, medical or otherwise. As is often the case, such memories are squeezed out of me by the mere twisting of the dial. Listening to Fred Allen’s 1937 St. Patrick’s Day broadcast, I was reminded of the kind of book I would have liked to have thrown at certain parties aforementioned.

Fred Allen is always good for a few laughs, however painful their elicitation. Annotating his quips can prove more rewarding still. Well before the hosts of our present day chat shows, satirist Allen raided the daily news for his weekly radio programs. In his Town Hall News (“sees nothing, shows all”), Allen commented on the goings-on in New York City, on politics, the economy, on culture high and low. Here is the first of the 17 March 1937 Town Hall News bulletins:

New York City, New York. Dr. R. P. Wodehouse, speaking at the American Institute of General Sciences, claims that hay fever and asthma are increasing in this country. Dr. Wodehouse says clearing up of native vegetation and its replacement by alien plants will add to number of victims.

Allen’s reading of this news item is followed by a skit demonstrating the wide-ranging effect the predicted rise of allergic reactions might have on the afflicted urbanite. This time, though, I was more interested in Allen’s source than in his take on it. My curiosity being immune to ulcers, I soon caught up on R. P. (no relation to P. G.) Wodehouse and his endeavors to “win the secret of a weed’s plain heart” (a quotation prefacing his 1945 study on Hay Fever Plants).

I wish R. P. Wodehouse had been a household name where I grew up; but, as the good doctor reminds me, by quoting John James Ingalls, “grass” is the “forgiveness of nature.” I’ll have to learn to let it grow over my own family plot—and concentrate instead on finding out how to avoid another catastrophic invasion of my oral flora. To cure my foul mood, a generous dose of Fred Allen is indicated . . .

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Your writing makes me smile out loud.

LikeLike

Thank you, Clifton. Given the state of my kisser, I\’m happy to be smiling by proxy.

LikeLike