Scoop up a tidbit, seemingly at random, however half-baked or nutritiously dubious. Ask what made you stick your fork—or spork or chopstick—in it. Reflect on why that morsel suits your palate, if indeed it does, at that particular moment in time. Present your thoughts on a platter meant for sharing. Hope for company, but don’t count on it. That, in a coconut shell has been my approach to writing for the web since I commenced this journal back in the blogging heyday of 2005. Eight hundred and forty-seven entries on, I am still at it, even though my diet, constitution and taste for potluck have changed considerably.

Not that I know exactly what those “Million Casks of Pronto” alluded to in the title of this blog entry contain; but more about that in as “pronto” as I can manage, especially since, as Wordsworth might have put it, these are lines composed a few minutes from Bronglais Hospital, where I went—and went under—for an endoscopy today. Gallstones be damned, I am in a reflective mood, and those “Casks,” which were tossed onto the airwaves back in 1924, have been on my mind for quite some time now.

As its title suggests, broadcastellan—a neologism I chose to declare myself keeper and carer of broadcasts—was, at least initially, devoted to thoughts on radio, and to radio of the pre-television age in particular; or, to be more specific still, to plays written for and aired on US American network radio during the quarter century or so when sound-only broadcasting was the main source of home entertainment in the United States. Those under-appreciated but once ubiquitous products of culture were the subject of my 2004 doctoral dissertation Etherized Victorians. The dissertation was completed about a year prior to the inauguration of this blog, which was conceived as a non-academic extension of it.

When Immaterial Culture, my study on the same subject, was published a decade later—not long after I had started teaching art history—broadcastellan increasingly branched out to engage with other commodities of western culture, including works of art and their curation. As a result, this journal, recherché as it was always acknowledged to be, lost some of its definition, even though it continued to reflect my everyday by considering said products under the circumstances in which I encountered them.

That my exit from academia in 2024 coincided with the one hundredth anniversary of plays for radio strikes me as an opportunity to reconsider the thematic boundaries of this journal and, more broadly, to revisit the question of definition.

In my teaching, I tended to generate debate by insisting on the importance of defining the fields of our investigation—be it landscape art, postmodernism, or the visual gothic, my lectures on which I am in the process of publishing on my website. Our definitions of terminology, of subjects and positions, may differ so fundamentally from what others think we might mean to say that it strikes me as essential to enter any discussion by saying something like “When I say X, I mean y.” Rather than encouraging the formulation of a definitive “X,” the idea was to keep expanding on the “y,” to revisit and revise our definitions instead of settling for the first, let alone borrowed one, that seems to fit the purpose.

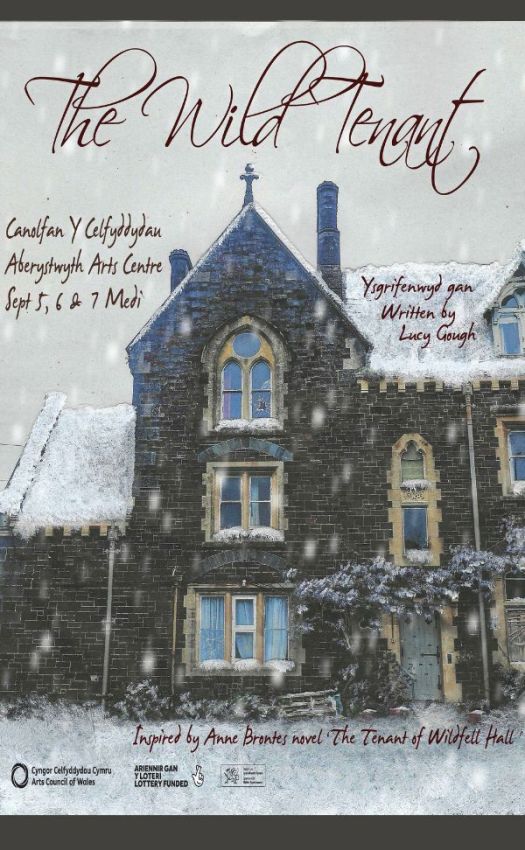

Defining rather than simply claiming our territory is a responsibility that I felt I had but did not quite meet when, in February 2024, I introduced an event at the National Library of Wales, which I had co-organized with playwright Lucy Gough, whose currently touring play The Wild Tenant, a dramatic and lyrical tour de force character study of two lovers in a violent and abusive relationship defies definitions and contests boundaries as an original play “loosely inspired” by Anne Brontë’s novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, which Gough makes no claim of having adapted.

The occasion of the commemorative event at the National Library of Wales was the one hundredth anniversary of A Comedy of Danger by the novelist-playwright Richard Hughes, who not only embraced his Welsh heritage—and thus asks to be considered in a Welsh context—but who is widely credited for having written the first play for radio to be commissioned and produced by the BBC or, indeed, by any broadcaster.

Now, at the event—which also featured a performance of Danger—guest speaker Alison Hindell, Commissioning Editor of Drama and Fiction for BBC Radio 4, alerted the audience—the crowd assembled and listeners tuning in remotely—to the fact that plays for radio had been written for and broadcast by the BBC well before Danger went on the air in January 1924, and that a play for children by Phyllis M. Twigg, writing under the pen-name Moira Meighn, was produced as early as Christmas Eve 1922.

Without disregarding the sexist implication of the widespread silence regarding the verifiable broadcast of Twigg’s “Truth About Father Christmas,” I want to focus on the issue of defining the territory: just what qualifies as a play for radio? And who, based on what definition, gets to cast the verdict on the definitive answer to the vexing question of “Who’s on First?”—to conjure memories of a famous comedy routine originating on radio.

One reason Richard Hughes is credited as the author of the first radio play, apart from being male, is that radio plays were, from the start, generally, and to my thinking, misleadingly termed “radio drama,” suggesting that plays for the air are more closely aligned with stage drama than with literature. Hughes had already written a play for the theater—The Sisters’ Tragedy (1922), which meant that he was regarded as a playwright and therefore, presumably, as someone qualified to devise a play for the new medium of radio, a product deserving of the term “drama.”

The determination of what constitutes the first play for radio is a matter both of definition and of authority to make that definition stick. Is radio drama? Is it theater? Could not any combination of voice, music, and noise (meaning, non-musical, non-verbal sound)—that is, any and all of the infinite ways of playing with sound and silence conceivable or yet to be imagined, provided that they emanate from a broadcasting studio—be considered “radio play”? I, for one, think so; but that is not how things—and thinking about so-called radio drama—has played out.

Just about the time that A Comedy of Danger first aired in 1924, the US radio station WGY, Schenectady, held a competition whose “object,” according to the July 1924 issue of The Wireless Age, was to “develop a type of play especially adapted to radio presentation, a type of play that will tell its story through an appeal to the ear and imagination just as the screen play [pictures being put in motion without recorded sound at the time] is directed exclusively to the eye.”

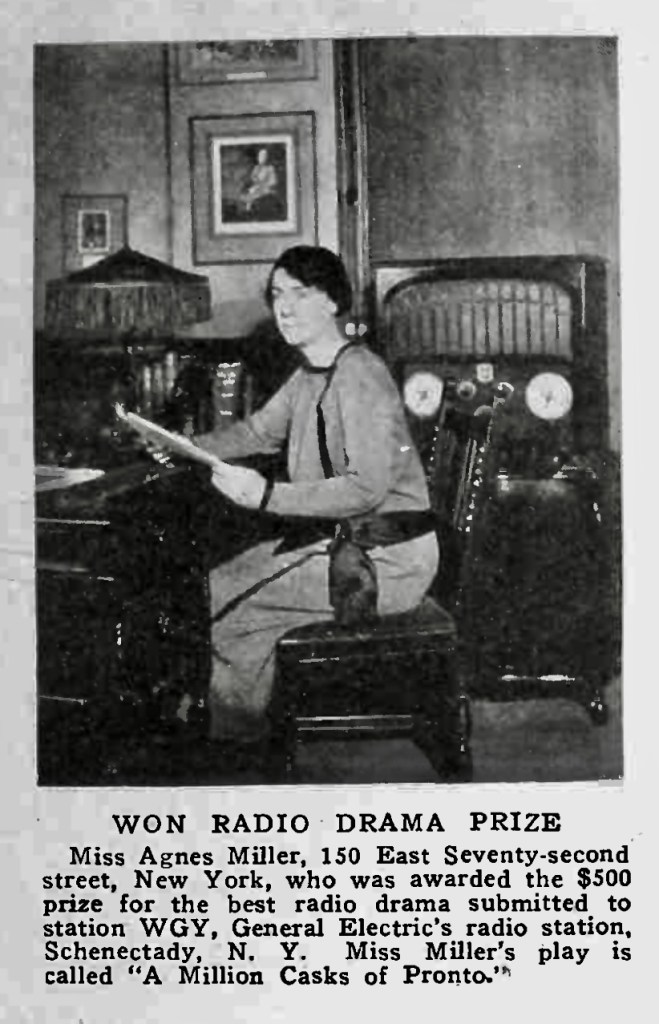

The winning entry was A Million Casks of Pronto by Agnes Miller of New York City, who was awarded the cash prize of $500 for her submission. The play was readied for wireless transmission in June 1924. It was performed by the same troupe of actors—the WGY Players—who are credited with originating radio plays in the US, albeit in the form of adaptations of stage plays, in 1922.

According to the 14 June 1924 issue of Radio World, rival submission in the 1924 playwriting competition included The Happiness Expert, a “comedy drama” by George Leber of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; The Man Who Would Not Be King, a “history drama” by John J. Kallen, also of the aforementioned metropolis; The Fiend, a “melodrama” by Charles U. Read of Upper Sandusky, Ohio; Hand Up, a “farce” by John Kendrick Stafford of Troy, New York; Out of the Past, a “romance” by Esther Swartzberg of Schenectady, New York; They Just Disappear, a “mystery drama” by Harry H. Stevenson, likewise of Schenectady; and Bootleg, a “drama” by Zeh Bouck of New York City, who would go on to write an instructional “survey of the opportunities in the field” titled Making a Living in Radio (1935).

Labels such a “melodrama,” “farce” and “history drama” bespeak attempts at defining the radio play as embedded in the traditions of western drama, although “romance” is a nod to medieval tales of chivalry and pre-novelistic fiction. Agnes Miller herself, in her article “Radio-Drama Writing” (published in the August 1924 edition of The Writer) declared that

is safe to say that the first point to which the radio playwright will do well to pay special attention is dialogue. The introduction of special noises and sounds to give setting and speed action has of course aroused great interest, because the idea is spectacular. No doubt much ingenuity can be exercised by playwrights in suggesting such sounds and by studios in producing them. They unquestionably add special concrete dramatic interest to a production, and how far they can be made use of is a very interesting matter for experimentation rather than speculation; but dialogue is really the radio play’s whole foundation, for how else, in radio drama, is plot to be unfolded, or character depicted, save through this means?

Miller, who uses the terms “radio play” and “radio drama” interchangeably, in a single sentence, appears to have thought of her “dialogue” for the medium in terms of the theater. “This is the first play I have ever written,” she was quoted in the New York Times (20 Apr. 1924). And yet, she freely admitted, she had “never taken any courses in dramatic writing,” adding that her “profession is writing.”

In fact, Miller had not long written The Linger-Nots, a series of three adventure novels for girls. Unlike the “Radio Girls,” another popular series of juvenile fiction published at that time, The Linger-Nots makes scant mention of the wireless craze, even though one of the novels—The Linger-Nots and Their Golden Quest—features a sled named “Radio,” and another one, The Linger-Nots and Mystery House, contains a reference to the “wireless.”

How Miller responded to the medium I am unable to tell, as no recording of the play is extant. According to a contemporary article in the Washington DC Evening Star, “many” of the “important situations” in Miller’s play were “constructed with the view to interpretation by sound devices, which indicates the experimental nature of the assignment. I doubt Miller had ever listened to Comedy of Danger, given that Hughes’s play was first performed in London and Cardiff.

A year later, in 1925, Sue ‘Em—billed as the “First Radio Play Printed in America”—was published by Brentano’s. Written by Nancy Bancoft Brosius, a “young librarian” from Cleveland, it was prefaced with remarks by the editor, journalist and actor Thurston Macauley, who held that “[w]riting a play to be produced before the microphones is as different from writing a play for the legitimate stage as is the preparation of the movie scenario.” If those distinctions had been clearly made, and its potentialities been realized, the radio—or audio—play would surely enjoy greater prominence, independence and support today.

Rather than definitively declaring plays like A Comedy of Danger, A Million Casks of Pronto or Sue ‘Em to be radio firsts, I am intrigued by the ways in which such pioneering performances defined or delimited radio playfulness, a playfulness that, I explained elsewhere, would later be curtailed by the system of network broadcasting which, at that time, was not yet in place.

It dawned on not long after deciding to pursue my studies that what draws me to the marginalized field of radio play as a hybrid of drama and literature is my queer identity. I am not in the game of fixing meaning. I am for a playfulness that defies absolutes, thrives on potentialities, and encourages a myriad of definitions, mired as my endeavours are in what Halberstam refers to as the “queer art of failure.”

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A great read. I’m researching Phyllis Twigg for a biography on her, and those comments re what defines a radio play/drama certainly resonate. I wonder what Twigg would have made of Hughes being credited as the first… or if she’d have known he was credited as the first in her lifetime, since so much of broadcasting history seems to have come in after these pioneers had died. Thanks once again.

LikeLike

All the best for your research project. May “The Magic Ring for the Needy and Greedy” provide a few morsels for thought to carry you through the lean season of slim pickings. Please consider letting me know how it all turned out and where the dish is served.

LikeLike

Thanks, much appreciated. I’m co-writing it with her great-granddaughter, so we’re discovering some nice family archives (that the family didn’t know about, stuffed in shoeboxes in the attic). A lot to sift through, but we’ll get there in time! We’ll keep you posted.

LikeLike