Get out much? Going places? Ready to take the part of “tourist”? Loaded with loathsome connotations, “tourist” has become a tainted word associated with a lack of regard for the cultures and customs of people who are forced to host the multitudes heading south for a few rays of sunshine and a dip in the sea, or whatever the local attractions the attractiveness of which the locals are promptly deprived by strangers that temporarily lay claim to them.

I am a “visitor,” not a “tourist.” That is a distinction I have always insisted on making when the latter label is affixed to me by New Yorkers, native or otherwise, who assume that my non-native tongue will stop wagging eventually to lick stamps set aside for picture postcards showing sights in the absence of which, once my “vagabond shoes” are back where they presumably belong, I am destined to suffer those “little town blues.”

To my mind, “visitor” better represents the close relationship that I—made in Germany, remade in/by NYC and based in Wales, as my Instagram profile proclaims—have with certain places, including Manhattan, whose sounds I recorded during my first visit in 1985 so that I might envelop myself in the metropolitan air by playing them back in the smalltown confines of my parents’ house.

Not that returning to places we once called home always feel like a homecoming, as my visit to that house in December 2022, after an absence of thirty-four years, persuasively drove home.

It was on that trip to the motherland that I went back as well, albeit not for the first time, to Museum Ludwig, the opening of which in 1986 I had greeted as a sign that Cologne had finally moved out of the shadow of the cathedral that towers over the cityscape like a two-fingered salute.

Coming back, I was relieved to find that, during my absence, Museum Ludwig had not stood still and was still committed to engaging with the here and now, as its exhibition series Hier und Jetzt promises to do. Especially reassuring to me was the series’ 2022/23 iteration Anti-colonial Interventions (8 Oct. 2022 – 5 Feb. 2023). “Identity and Otherness” had long been a thematic strand of my art history teaching, whose attention to the marginalized derives from a personal history of dislocation, estrangement, and longing.

Of all the practices presented under the Hier und Jetzt banner that year, the one resonating most with me was that of Tegucigalpa-born, Basel-based artist Pável Aguilar, a reference to whose project Acordeones Anticoloniales would become an opener for discussion in my final postgraduate seminar series “Artworld: Contemporary Practice in Context” as a prime example of conceptual art that cannot be reduced to or understood as an isolated aesthetic object.

Even after my self-imposed exile from academia in 2024, Acordeones Anticoloniales continued to reverberate, not least because, in my idiosyncratically associative ways, I was reflecting on migrant selves and identities in flux while preparing for Retroactive Selfies: The Return to/of the Boy in the Avocado Bathtub, an exhibition of personal photographs dating from the 1980s to which my experiences of living in Cologne and relocating to New York City are key.

Whenever I travel beyond New York City and certain parts of western Germany, I begrudgingly accept the label “tourist” as valid, even though I detest it as much as I do the bourgeois notions of “leisure” and “vacation,” the latter word having its roots in the Latin “vacare,” meaning “unoccupied.” I can only hope that my wandering mind will never be quite as vacant as that, and that my body in motion does not simply increase the rate of occupancy in the rooms I occupy while away.

What are we taking away with us from our travels? How are we transformed by our perambulations abroad? And what are we leaving behind, apart from the money from which we were parted, or that suitcase stuck in Zürich after my trip to Naples in October 2024? Resentment, perhaps?

“When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” a proverb attributed to Saint Ambrose advises, and “if you should be elsewhere, live as they do there.” As sound as this advice might sound, it is difficult to heed in a globalist age of neo-colonial tourism, in which an industry catering to the temporary and voluntary migration of millions of people makes it challenging to determine whether locals perform their customs primarily for others or preserve them for themselves.

The strains of “Funiculì, Funiculà” emanating from backtrack-enhanced violins played by unsung performers in the presence of a captive audience of train passengers on day trips from Naples to Mount Vesuvius and Pompeii suggest that locals, cap in hand, draw on the past to package and parcel it out for whatever coinage may be extracted from the tourists whose money so often eludes communities deluged by the locust-like throng of itinerants passing through.

The Mount Vesuvius funicular, whose completion was commemorated by that Neapolitan song, was destroyed in 1944; but the crowds now bussed to the site keep clambering up to its crater for an eye-catching selfie with views of the shore where rescued migrants end their perilous journey to face the wrath of the Italian far-right.

If it seems harder for travellers to find and define the authentically “local”—if indeed they can discern or trouble themselves to go in search of it—it is because the “local” is often confused with the “traditional,” which I take to mean the “conventional” that is elevated to cultural representativeness by virtue of its endurance.

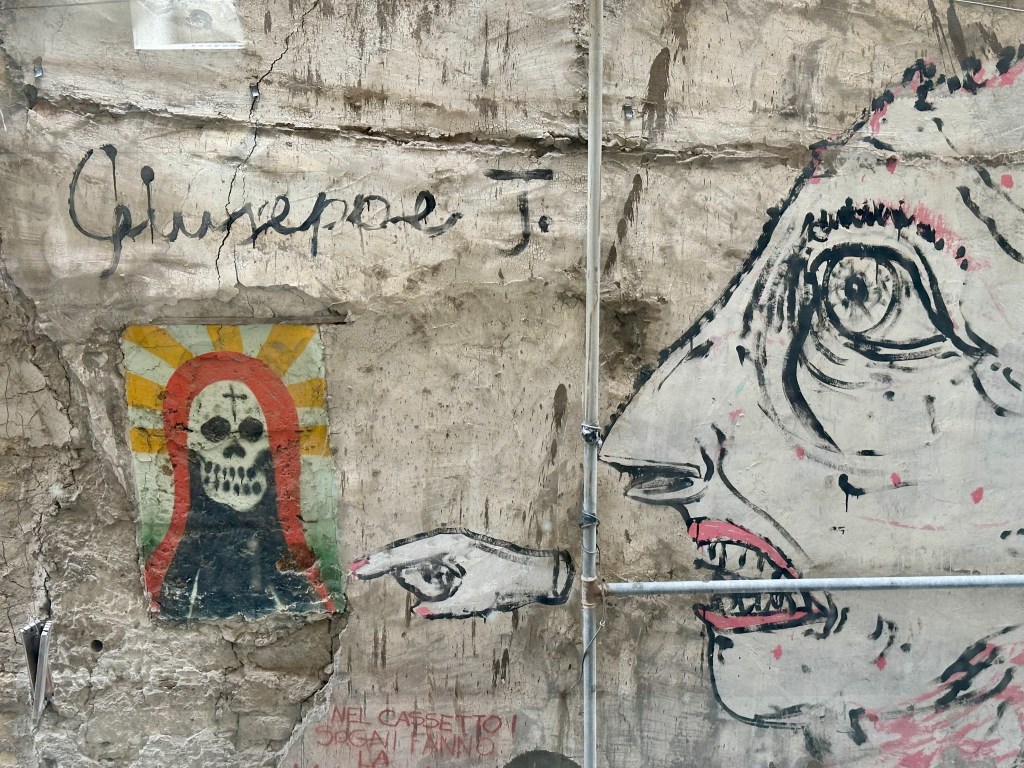

In Naples, I was attracted equally by the paintings housed in centuries-old places of worship as I was by the graffiti that now covers the façades of those houses. Both visual practices—painting and graffiti—are local; but whereas one represents the “traditional,” the other confronts or affronts it, along with the sensibilities of those who prefer their culture riveted in place and time, despite the fact that murals, old and new, can be found all over the place. “Fresco” means “fresh”—but I am aware that this does not apply to its date of execution or to the relevance of its subject matter to our times.

Not that Naples is as fusty as its catacombs. It is far more culturally diverse than the regional cuisine dished out in its ubiquitous pizzerias. You might be searching in vain for a Nepalese eatery—the spirit of Saint Ambrose raises an eyebrow at the very thought—but you will readily encounter international and contemporary art.

One highlight of my visit there was an early afternoon at Museo Madre, the Donnaregina Contemporary Art Museum, where, once again, I was unexpectedly drawn in by visual cultures of the other Americas beyond the United States.

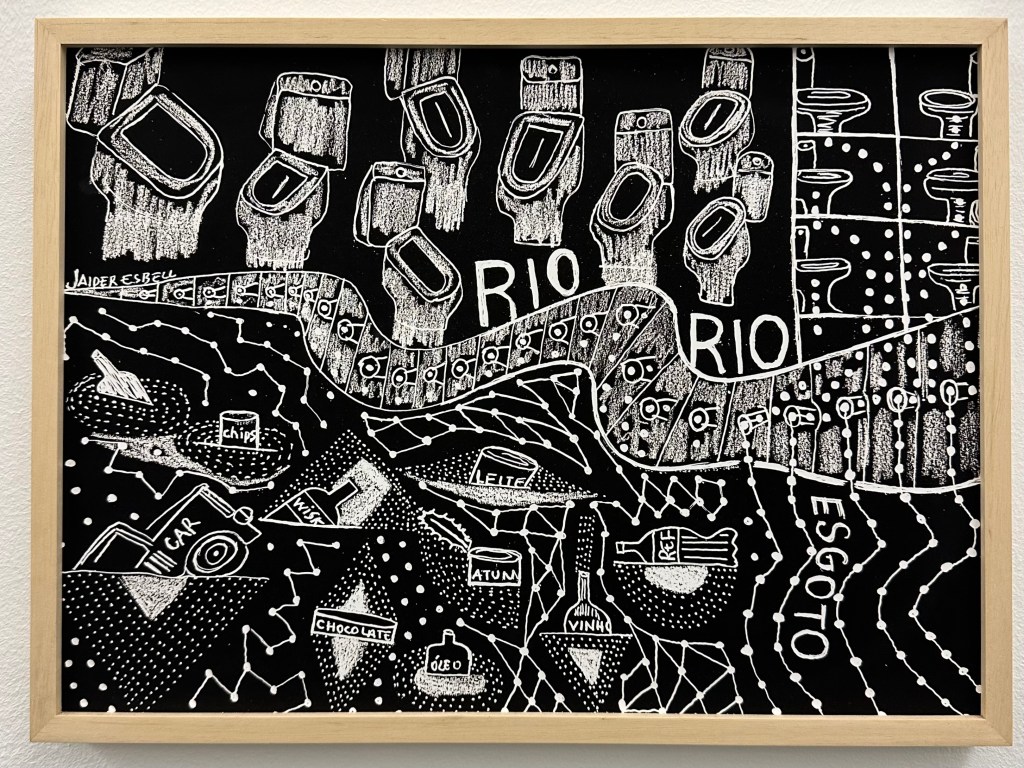

Vai, Vai, Saudade (4 July – 4 Nov. 2024), curated by Cristiano Raimondi, presented itself as a “poetic pathway, exploring a series of stories related to the art produced in Brazil since WWII.” The webpage for the exhibition refers to those “stories” as merging “travel notes” intended to “form a free but interconnected exhibition itinerary of formal and conceptual, spiritual and earthly, political and geographical themes.”

While some of the exhibited works corresponded—or can be construed to align—with European and US American modernism, many of them were startlingly extra- or trans-modern, inviting—and indeed demanding—revisions of canonical art history and its continued preoccupation with the Western avant-garde at the expense of anything that cannot be subsumed under that rubric.

My brief stay did not enable me adequately to engage with the works on display; but the sense of disoccidentation, of being transported from the confines of the familiar—no doubt heightened by the location in which the show was staged—lingers along with a suspicion I have long harbored and found confirmed during my teaching stints in mainland China: when it comes to the cultures of the world, I know far less than the supposed “other” (exoticized or marginalized) half of it. Knowing at least that much, I always appreciate creative practices that catch hold of my Socratic ignorance and assist in dis-conditioning my thinking.

Vai, vai, Saudade, with its musical reference to a samba composed by Heitor dos Prazeres (1898–1966)—a Carioca artist who, the curator informs us, “was among the first to be subjected to censorship by the military dictatorship in 1964”—recalled to mind the surprise I had at Museum Ludwig two years earlier when I came across those “anti-colonial” accordions and other musical instruments such as the quijadas, güiros and caracols with which Pável Aguilar, who is a classically trained musician, creates dialogues between moored and migrant objects of material culture and fills with sound the museal void in which the values they manifest and the voices they raise are so often in danger of becoming voided.

With Una güira para …, his playful interventions at Museum Ludwig, Aguilar engages the collection of an institution whose declared object is our appreciation of modern, postmodern and contemporary art practices but that, in its curatorship, at least until recently, tended to privilege the “here” and whose representation of “now,” according to the Museum’s director Yilmaz Dziewior, has been dominated by the works of white, heterosexual male “Amerikaner,” a bias that Dziewior aims to contest but unwittingly reflects, as is evident from his use of the word “Amerikaner” when referring far more narrowly to US Americans.

In an anticolonial move, Aguilar strategically yet seemingly randomly inserts a range of colouful güiros, Latin-American percussion instruments made of hollowed-out gourds, into the museum environment, where they are brought into contact—commune or compete, depending on our reception—with works by European modernists whose names he inscribes on each instrument’s surface.

Among those artists are celebrated Primitivists such as Pablo Picasso and Herman Scherer whose avant-garde practices entailed unacknowledged appropriations of works from non-Western cultures, sculptures and vessels that were stripped and emptied of their historical, ritual and spiritual values.

What would happen if a güiro were to sneak up—as I misremembered that it had—on Geburt des Menschen (1919), a sculpture by Otto Freundlich prominently on display at Museum Ludwig? So positioned, the güiro could serve as a reminder that, not unlike marginalized cultures, modernist art and its makers likewise faced existential threats in the past. Freundlich was killed at Majdanek extermination camp, the victim of a fascist regime that defamed his work as “entartet.” I hear you, the güiro might say.

Museums are not as safe a sanctuary for art as their high walls, guarded galleries, or imposing exteriors may lead us to believe—certainly not in Germany. National Socialists destroyed hundreds of works by Expressionist painter-printmaker Otto Müller, to whom Aguilar does respond with a corresponding güiro.

Sanctioned by a museum as evidence of its endeavors to decolonialize its collections, or at least to revisit its curatorial mission, Una güira para …, while not proposed as a critique of the institution of which it avails itself as a platform, nonetheless assists in making the history, the origins and shaping of the collection visible. Who he? I asked myself as I struggled to match Una güira para Joseph Haubrich with the artworks surrounding it. Find out, the güiro teased me.

Josef Haubrich (1889–1961) was an influential figure in the Cologne art scene of the interwar years whose collection is now part of Museum Ludwig. In his home, Haubrich is said to have saved works by German-born Jewish artists from destruction by claiming them to be French, a case of misstated identity that institutions under the scrutiny of the Reichskulturkammer would have struggled to make. Born into an era in which curators and artists can collaborate without threat of persecution, a güiro bearing Dziewior’s name is now in the museum’s collection.

The accordion bellows that Aguilar introduces into the gallery take their place on the walls as confidently as the güiros occupy the plinths. Emblazoned with words and phrases representative of an emerging anti-colonial movement and lexicon, they proclaim the urgency of such creative and collaborative interventions. For all their vibrancy, they bespeak the limitations of academic parlance and institutionalized practice that, like the hollow and no longer musical instruments hung on the gallery to assume the status of framed canvases, cannot by itself effect the actions that it affects to advocate, with whatever degree of sincerity or fervor.

Unlike the accordion bellows, the shell trumpets placed in the center of the same gallery are unadorned readymades. Far from being “alien substances” in the “organism” of the museum—to use the hateful terminology with which museum director Thomas Messer justified the cancellation of Hans Haacke’s 1971 exhibition at the Guggenheim—their presence in an art museum no longer seems to require justification.

The conches, like the accordions, are mute. They do not interrogate the system in place to validate or reject such migrant objects. And what is being or has been rejected, including those “inconvenient objects” in museum collections I aimed to bring into focus in one of my curatorial projects, so easily escapes our notice. Aguilar knows, however, how to make those objects speak, and he does so compellingly in performance.

Posting these rambling notes (which constitute the 850th entry in the broadcastellan journal) on the twentieth anniversary of my arrival in Wales, England’s first colony, on 5 November 2004, I am alive to the othering “there,” the lasting colonial legacies to which the Roman walls and towers of Colonia bear witness as well. In the case of Wales—the fabled land of song—the fallout is a suppression of its indigenous language, the denigration of its visual culture, and the exploitation of its natural resources.

“Partly because of empire,” Edward Said has claimed, “all cultures are involved in one another; none is single and pure, all are hybrid, heterogeneous, extraordinarily differentiated, and unmonolithic.” While this involvement is rarely an even exchange, the rejection of “purity”—a dirty word indeed—helps contemporary practice move beyond trauma discourse to achieve what Kader Attia terms “repair” and what Afrofuturism articulates in its title: a vision to forge ahead.

What moved me most about Aguilar’s practice are its lyrical qualities and the pathos with which his work appeals to via multiple channels or media. Acordeones Anticoloniales does not just tell but sing of the accordion, an instrument of German origin that, by way of migration, was transformed and invested with new meaning in Colombia—a member of the free-reed aerophone family that got away. It was returned in part and in parts to insist on belonging.

According to the lyrics to the music playing in Aguilar’s video installation, which I shall purposely leave untranslated,

[e]l acordeón fue nacido en Alemania, y para charlar fue nacido aquí en la Costa. Por eso que decimos que es música colombiana, y también es colombiano para charlar a quien la toca.

The recording encourages those German-born museum visitors who immediately associate the accordion—as I did—with romanticized images of seafaring, the ever-white “La Paloma” and the fair-haired German actor Hans Albers—a cultural icon burdensomely bequeathed to me by my grandparents’ generation—who played the instrument in Grosse Freiheit Nr. 7, a film produced in although ultimately banned by the Third Reich, to stop singing the same familiar tune of their imperialist and colonizing forebears and listen out instead for the sound of voices or, as Aguilar’s Ocean Echoes (2022) proposes, the voices of sounds other than those of their presumed own by heritage.

Inviting us to hear the accordion resounding in Colombia and making a noise for the indigenous cultures of Honduras with the aid of the caracol—which, not unlike the accordion, is often in the hands of people whose voices have remained largely unheard, but that sings to us of the sea unaided by our breath—Aguilar’s sound art, performance and conceptualism open minds when the written or spoken word reaches its translative limits and where art predicated on objecthood hits the wall. Perhaps, playfully to recontextualize the words of Walter Pater, the most resonant art of today aspires to the condition of music.

I am a “visitor,” not a “tourist.” The difference is a matter of receptiveness—a willingness to be all ears.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.