“Many plays have been broadcast, but none of them seems to me to have the pep that is needed to get not merely across the footlights but across the ether.” Complaints such as this one are all too familiar to me; in fact, they were launched so frequently against radio culture that, years ago, they prompted me to contest them.

To misappropriate the famous question posed by the feminist critic Linda Nochlin, I asked “Why Are There No Great Radio Writers?” The objective was not to find examples to the contrary—those queer, quirky and quicksilver exceptions that can serve to prove the rule—but to query the question itself as (mis)leading and to expose the biases underlying it.

My study Immaterial Culture: Literature, Drama and the American Radio Play, 1929–1954 opens with a mockery of rants against—and wholesale dismissals of—radio culture in the 1930s and 1940s, when radio playwrights, in the United States at least, catered to audiences larger than those reached by writers for stage, screen and print media.

As Variety radio editor Robert Landry noted, radio’s very popularity, its ubiquity in everyday life, was the chief reason for discrediting it:

Radio is vaudeville. It is trivial. It is the market place. It concerns ordinary people and the things they think about. In short radio is educative in a practical and basic sense that disturbs those who prefer to think of education as one Ph.D. dazzling another Ph.D.

Landry’s populist stance and its ridiculing of academia is hardly reassuring; it encouraged me to take on the segregation of radio writing and its absence in anthologies devoted to drama, poetry and literature, as a result of which doctoral studies like my own “Etherized Victorians” have remained largely disconnected from the vast community of old-time radio afficionados.

Judging by the lack of engagement with the overpriced volume I eventually managed to get published, Immaterial Culture failed to build any bridges; but that does not deter me, now that I have burned my bridges to academia, from returning to the site of construction.

Early in 2024, I staged a public event commemorating the one-hundredth anniversary of the inaugural broadcast of Comedy of Danger by Richard Hughes, which is reputed to be the first radio play, despite evidence to the contrary. As I said previously, the determination what constitutes the “first” radio play depends on our definition of “radio play.”

Is it scripted dialogue accompanied by sound effects? Could it be any combination of music and spoken word? Or perhaps aural play divorced from the confines of words and music? Does a “radio play” need to be broadcast, even, or might it suffice that it was conceived or intended for the medium?

I scratched my head debating those questions when I started out researching so-called “old-time radio” back in the late 1990s. How was I to delimit my study? Would I end up writing speculatively about plays of which only titles remained in print and no recordings were extant?

As I was trying to persuade scholars of literature and drama that the radio play was an unduly neglected hybrid of both, I determined to focus on published scripts for plays of which, in most cases, audio recording were available for listening, thus allowing me to take them in as radio plays were intended to be appreciated, the script serving mainly as an aid to listening and as evidence that some scripts were deemed significant enough to warrant publication in print.

The first radio play to be published in the US—Sue ‘Em by Nancy Bancroft Brosius—dates from 1925. Here, too, the “first” needs to be approached with a generous pinch of sodium chloride, as “publication” may be misconstrued as meaning a printed volume, which would mean to disregard the appearance of broadcast scripts in contemporary periodicals, where I went in search of them.

What intrigues me about the claim I quoted earlier—that “none” of the “[m]any” broadcast plays “have the pep” to come across over the wireless—is that it cannot readily be verified or disputed. The author, identified only as “The Listener-In,” does not go into any specifics regarding the listening experiences on which the critique is founded.

Nor could I, in this instance, draw on experiences of my own, considering that the statement was made at a time in radio history about whose programming we know little and pretty much all we have left to go on is hearsay. After all, the comment appeared in the November 1924 issue of the British periodical Modern Wireless; and except for the lionized Comedy of Danger, radio plays of that era survive neither in print nor recording.

“Some time ago the BBC advertised for plays suitable for broadcasting,” the “Listener-In” acknowledges; but the article, appearing some ten months after the first production of Comedy of Danger in January 1924, suggests that little effort was made to keep up with developments in the field, concluding with vague predictions instead: “I feel, somehow, that none of those submitted will quite come up to the standard.”

Now, Modern Wireless did not concern itself primarily with radio programming such as the plays at which the “Listener-In” scoffs. “Somehow all of them seem to lack vim, zip and driving force,” the writer continues regardless:

None of them so far has moved me to tears; in fact, I cannot even remember writhing in my chair with suppressed emotion, running fevered hands through my hair, tearing off my collar, gnashing my teeth, or giving other signs that my deepest feelings were being stirred.

Clearly, the technology might be “modern,” but the views on drama are positively Victorian. The “Listener-In,” as it turns out, is not sticking out a tongue at radio playwrights and producers but aims to keep it firmly in cheek by “presenting” the BBC

free of charge with a thrilling drama of love and hate […]. You will, I think, agree that it has the right atmosphere, and that if it were broadcast it would make even the most hardened loudspeaker choke a little.

Had I come across a rare script for an experimental radio play? Something akin, perhaps, to Hans Flesch’s Zauberei auf dem Sender (Sorcery at the Radio Station), which was broadcast from Frankfurt on 24 October 1924 and subsequently published in the German magazine Funk (meaning “Broadcasting”) in its December 1924 issue? As it turns out, the “thrilling drama” proposed for the airwaves by the “Listener-In” is no such experiment.

Extravagantly titled “Run to Earth, Or The Foiler Foiled,” the short script has few of the qualities that make for sound on-air delivery, excepting a premise that, in its self-reflexivity, bears a resemblance to Zauberei auf dem Sender and anticipates the efforts of Norman Corwin, the preeminent radio playwright of network broadcasting in the United States some fifteen to twenty years later.

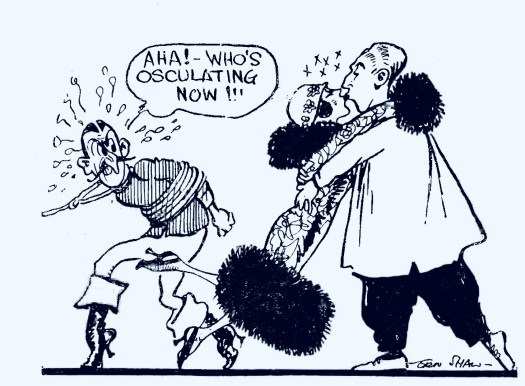

Unlike the radio plays by Flesch and Corwin, however, “Run to Earth” is about the wireless without being a play for the wireless. To begin with, it has a “curtain,” comes with stage instructions (such as “advances to the front”) that could be of no assistance to producers or audiences, and, to show off its inadequacies to full disadvantage, features embellishments by the English cartoonist Ern Shaw, which illustrate what the script does not assist in making us see.

The scene set by the state instructions for “Run to Earth” is the “Village of Czrwxkzy in the Wilds of Electronia.” As the “curtain rises,” Professor Forbie, a “wireless experimenter,” “leaps from his chair, tears off the [head]phones, flings them on to the floor, dances on them, hits his pet corn a nasty one and subsides into a chair”—not visuals that a radio play could conjure in our mind’s eye without the aid of a narrator.

Something has given the Village of Czrwxkzy its bad name, and Professor Forbie is not going to take it sitting down. He reaches for the telephone and dials the number of the Electronian Broadcasting Company:

I wish to lodge a complaint about interference and illegal transmission. No, no, I did not say unequal emission. Illegal transmission. Very serious case. Goes on continually. Cannot hear myself think. What’s that? You will send down in the morning? Good. One can always rely upon the EBC to act promptly. (Hangs up telephone receiver. Rises[,] yawns and puts on a ferocious expression.) And now my interfering friend, we’ll see.

“[W]e’ll see,” indeed. “Run to Earth” makes us “see” little, especially not Forbie’s “ferocious expression.” After the wrongful incarceration of an innocent suspect, the culprit is apprehended and sentenced to death.

Gleefully inept as it is, the mock script tells us more about the identity crisis of Modern Wireless—and the transition of radio from an activity for hobbyist to a source of listening for tuners-in—than about the state of radio dramatics. An article published in the same issue acknowledged as much:

The wireless enthusiast has an entrancing hobby, but one which, like most hobbies, fails in some of its pleasure if it does not afford interest and entertainment to one’s family or intimate friends. For this reason the enthusiast would do well to remember that the reception of telephony without wires has lost its novelty for the layman and is now almost commonplace. Consequently, the entertainment radiated from the various stations of the BBC is alone of permanent interest.

Publishing “Run to Earth” in its “In Passing” column, Modern Wireless suggested that, before any modern(ist) approaches to plays for broadcasting could be advanced, the technology needed to advance as well. How could listeners take in avant-gardist plays if their equipment was “unequal” to it?

To paraphrase the Anglo-Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, once again, it is a case of the head being modern “though the trunk’s antique!” And unless further advances were made, Modern Wireless could stay in the business of making the “commonplace” of the airwaves seem like a playground for experimenters.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.