I had not long arrived in sweltering New York City for a month-long stay in my old neighbourhood on the Upper East Side when I learned that, across the pond, in my second adopted home in Wales, the painter Claudia Williams had died at the age of 90. I first met Williams in 2005. She was conducting research on a series of drawings and paintings commemorating the flooding of a rural Welsh community to create a reservoir designed to benefit industrial England. With my husband and frequent collaborator Robert Meyrick, who had known Williams for years and staged a major exhibition on her in 2000, I co-authored An Intimate Acquaintance, a monograph on the painter in 2013.

A decade later, an article by me on Williams’ paintings was published online by ArtUK on 28 May 2024; and just days before her death on 17 June 2024, I had been interviewed on her work by the National Library of Wales. So, when given the opportunity to write a 1000-word obituary for the London Times, I felt sufficiently rehearsed to sketch an outline of her life and career, as I had done previously on the occasion of her artist-husband Gwilym Prichard’s death in 2015.

Lunch in the yard with Gwilym Prichard and Claudia Williams

All the same, I was concerned that it might be challenging to write another “original” essay, as stipulated by the Times, on an artist about whom I had already said so much and whose accomplishments I was meant to sum up without waxing philosophical or sharing personal reminiscences. In an obituary, salient facts are called for, in chronological order, as is a writer’s ability to determine on and highlight the essentials.

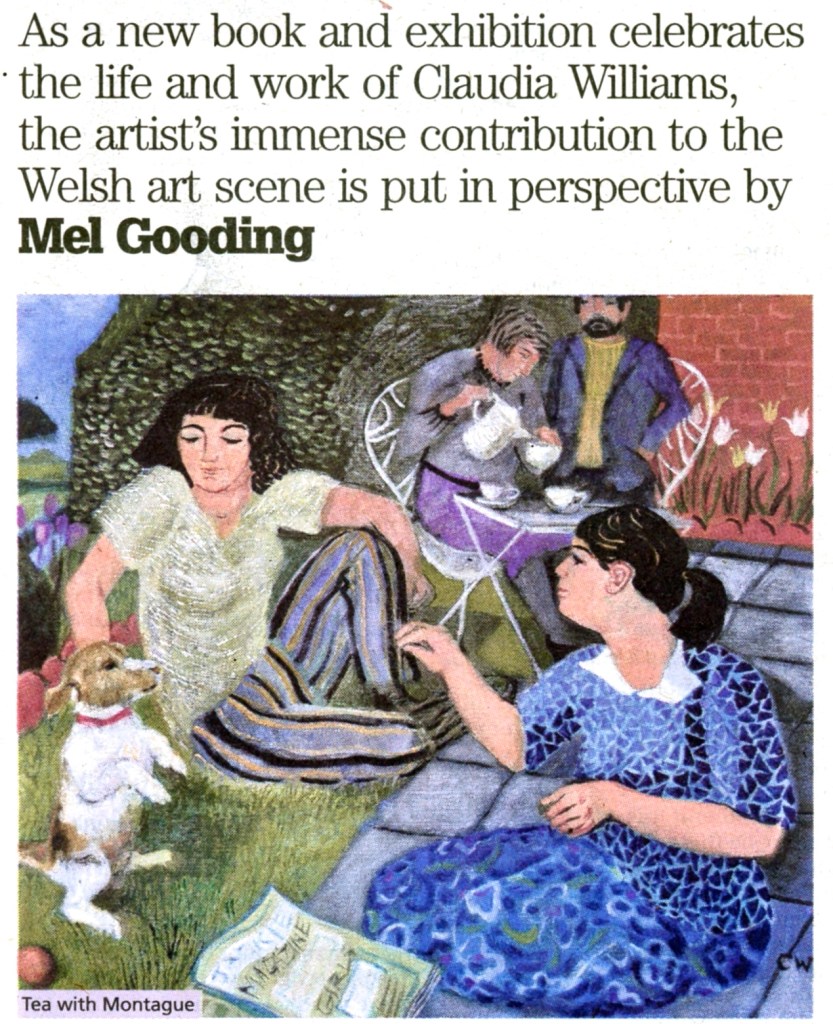

So I omitted recalling the enjoyment Williams derived from watching my Jack Russell terrier begging for food on his hind legs, a sight that inspired her painting Tea with Montague, or the “Mon Dieu” emanating from our bathroom when Williams and her husband, both in their seventies, intrepidly and jointly stepped into the whirlpool bathtub – slight episodes that, for me, capture Williams’ joie de vivre and her enthusiasm for the everyday.

Clipping of a newspaper article on An Intimate Acquaintance featuring my dog Montague as painted by Claudia Williams

In preparation for the monograph, Williams had entrusted me with her teenage diaries and other autobiographical writings, which meant there was plenty of material left on which to draw. Rather than commenting authoritatively on her contributions to British culture, I wanted to let Williams speak as much as possible in her own voice, just as her paintings speak to us, even though we might not always realize how much Williams spoke through them about herself.

What follows is the tribute I submitted to the Times.

Continue reading ““[P]eople are always interesting wherever they are”: My Tribute to Claudia Williams for the London Times”