At the risk of sounding like a loser at a Vegas spelling bee, I am a serious eye roller. Like a roulette wheel on an off night, each circulation marks the extent of my displeasure. The other night, I was really taking my peepers for a spin. Judging from such ocular proof, you might have thought that more than eyeballs were about to roll. Indeed, it seemed as if I were going to face the Lord High Executioner himself. Instead, we were merely going to a production of The Hot Mikado. I just couldn’t warm to the idea of going camp on a classic that seems least in need of burlesque—or Berlesques, for that matter. Not that this stopped middle-aged troupers like Jack Benny, Bob Hope, and Groucho Marx to play “Three Little Maids” (as part of a war relief benefit broadcast); but, at least, those tuning in were spared the visuals.

If I was less than enthusiastic, it was mainly on account of Charley’s Aunt. That dubious Victor/Victorian dowager had way too many nephews—and “they’d none of them be missed, they’d none of them be missed.” Cross-dressing has long been on the none too little list of circus and sideshow acts that are more of a source of irritation than of hilarity. One strategically placed banana peel does more for me than two oranges nestling in a bed of chest hair. It’s a fruit’s prerogative.

The origins of my aversion date back to the time when I began to realize that what I needed to get off my chest one day was something other than the fur I was not destined to grow in profusion. I was about twelve. Still without a costume on the morning of the annual school carnival, I let my older sister, who was as resourceful as she was bossy, talk me into wearing one of the skirts she had long discarded in favor of rather too tight-fitting jeans. Being dressed in my sister’s clothes was awkward for me, considering that I was fairly confused about my gender to begin with, certain only about the one to which I was drawn. More than a skirt was about to come out of the closet, and I was not equipped to deal with it.

Responding to my calculatedly nonchalant remark that the costume was some kind of last-minute ersatz, our smug, self-loving English teacher, Herr Julius, told the assembled class that, during carnival, folks tended to reveal what they secretly longed to be, which, apparently, went well beyond the common desire not to be humiliated. No wonder Herr Julius did not bother to don a mask other than the one with which he confronted us all the scholastic year round.

Matters were complicated further by my wayward anatomy. Let’s just say that it didn’t require oranges to make a fairly convincing girl out of me; I was equipped with fleshy protuberances that earned me the sobriquet “battle of the sexes.” I wondered whether I was destined to shroud myself in one pretense in order to drop another. That, in a pair of coconut shells, is why cross-dressers and any such La Cage faux dollies were never to become my bag. And I’ve got a lot of baggage.

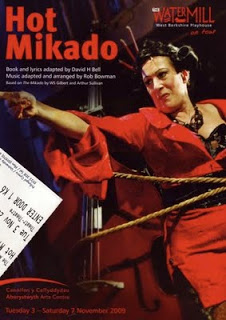

What has that to do with The Hot Mikado, the show I was so reluctant to clap my eyes on? As it turns out, not very much. I had been mistaken about the gender of the performer playing Katisha, the character on the poster (pictured above) that was advertising the Watermill production I caught at Aberystwyth Arts Centre.

Far from being some newfangled cabaret act, The Hot Mikado is seventy years old this year. Appropriating presumably WASPish entertainment for a younger and less exclusive audience, it was first performed in 1939 with an all-black, extravagantly decked out cast headed by the legendary Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in the title role. The currently touring Watermill production—which is soon to conclude in Girona, Spain—updates the carnivalesque spectacle in retro-1980s colors, with Manga and movie inspired costumes, as well as assorted references to Susan Boyle and British politics. The music is still jazz-infused Gilbert and Sullivan.

Set “somewhere in Japan” and produced at a time when Mr. Moto was forced to take an extended Vacation, the anachronistic Hot Mikado was all jitterbug without being bugged down by pre-war jitters. It is outlandish rather than freakish, amalgamated rather than discordant, qualities reassuring to anyone who has ever felt mixed up or unable to mix. A few bum notes aside, the production was hardly an occasion for any prolonged orbiting of orbs. The joyous spectacle of it kept even my mind’s eye from rolling, from running over the bones, funny or otherwise, that tend to tumble out of this Fibber McGeean closet of mine . . .

Related recordings

Greek war relief special (8 February 1941), featuring Frank Morgan, Bob Hope, Jack Benny and Groucho Marx singing songs from The Mikado

“Hollywood Mikado”, starring Fred Allen (11 May 1947)

Chicago Theater production of “The Mikado” (22 October 1949)

The Railroad Hour production of “The Mikado” (5 December 1949

I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities.

I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities.

Having spent a week traveling through Wales and the north of England—up a castle, down a gold mine, and over to Port Sunlight, where Lux has its origins—I finally got to sit down again to take in an old-fashioned show. That show was My Fair Lady, a production of which opened last night at the

Having spent a week traveling through Wales and the north of England—up a castle, down a gold mine, and over to Port Sunlight, where Lux has its origins—I finally got to sit down again to take in an old-fashioned show. That show was My Fair Lady, a production of which opened last night at the  In the house I now call home, I am surrounded by a great many works of art, from oils and etchings to ceramics and stained glass. When I moved in the walls were already crowded with images; and I felt strangely if understandably disconnected from them and my new surroundings. For this simple reason, our Welsh cottage soon came alight each evening in the ersatz glow of moving images imported from the Hollywood of the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s (a few exceptions notwithstanding). These pictures are projected onto a blind behind which unfolds the celebrated beauty of the Welsh landscape which, on a cloudless night, is more silver than the screen. For weeks after moving here from New York City (back in November 2004), a move worthy of a Daphne du Maurier thriller, were it not for my genial partner, I was unable to draw the blinds without bursting into tears, no matter how serene the scenery (our living room view being

In the house I now call home, I am surrounded by a great many works of art, from oils and etchings to ceramics and stained glass. When I moved in the walls were already crowded with images; and I felt strangely if understandably disconnected from them and my new surroundings. For this simple reason, our Welsh cottage soon came alight each evening in the ersatz glow of moving images imported from the Hollywood of the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s (a few exceptions notwithstanding). These pictures are projected onto a blind behind which unfolds the celebrated beauty of the Welsh landscape which, on a cloudless night, is more silver than the screen. For weeks after moving here from New York City (back in November 2004), a move worthy of a Daphne du Maurier thriller, were it not for my genial partner, I was unable to draw the blinds without bursting into tears, no matter how serene the scenery (our living room view being  The smattering of rousing captions that accompany the images sure smacks of desperation. How do you sell a forgettable thriller as a must-see? You resort to words and phrases like “kill” and “cold blood, “evil” and “insane,” “murder” and “monstrous secret” to align the indifferent material you are pushing with the neo-gothic literature known to sell. In radio dramatics, no words were more prominent than “murder” and “death.” “Love” doesn’t sell half as well as death. “Sex” might, but radio was too cautions to go where most minds—and the species at large—are on a regular basis. To this date, US entertainment is more tolerant of mutilation than titillation, owing chiefly if indirectly to the violence that is religion.

The smattering of rousing captions that accompany the images sure smacks of desperation. How do you sell a forgettable thriller as a must-see? You resort to words and phrases like “kill” and “cold blood, “evil” and “insane,” “murder” and “monstrous secret” to align the indifferent material you are pushing with the neo-gothic literature known to sell. In radio dramatics, no words were more prominent than “murder” and “death.” “Love” doesn’t sell half as well as death. “Sex” might, but radio was too cautions to go where most minds—and the species at large—are on a regular basis. To this date, US entertainment is more tolerant of mutilation than titillation, owing chiefly if indirectly to the violence that is religion.

Generally, we don’t regard our movie comings and goings as once-in-a-lifetime events, no matter how extraordinary the experience. In fact, we are inclined to opt for a rerun if a film manages to make us wax hyperbolic in our enthusiasm for it. To be sure, not many moving images have this force; nowadays, they are so readily reproduced, so instantly retrieved, that many of us won’t even bother to sit down for them, knowing that they can be had whenever we are ready for them. We miss out on so much precisely because we are comforted to the point of indifference by the thought that we do not have to miss anything at all. When I write “we,” I do number myself among those who are at-our-fingertipsy with technology. Last weekend’s screening of The Life Story of David Lloyd George at the Fflics film festival here in Wales was a reminder that films can indeed be rare; that they are fragile and subject to forces, natural and otherwise, that cause them to vanish from view.

Generally, we don’t regard our movie comings and goings as once-in-a-lifetime events, no matter how extraordinary the experience. In fact, we are inclined to opt for a rerun if a film manages to make us wax hyperbolic in our enthusiasm for it. To be sure, not many moving images have this force; nowadays, they are so readily reproduced, so instantly retrieved, that many of us won’t even bother to sit down for them, knowing that they can be had whenever we are ready for them. We miss out on so much precisely because we are comforted to the point of indifference by the thought that we do not have to miss anything at all. When I write “we,” I do number myself among those who are at-our-fingertipsy with technology. Last weekend’s screening of The Life Story of David Lloyd George at the Fflics film festival here in Wales was a reminder that films can indeed be rare; that they are fragile and subject to forces, natural and otherwise, that cause them to vanish from view.