Once Upon a Time in Radioland: A Kind of Ruritanian Romance

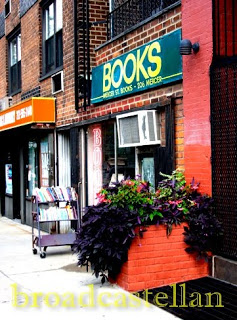

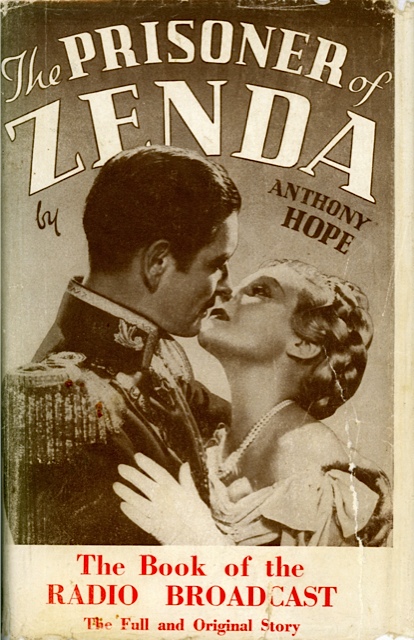

The other day, at my favorite bookstore here in Aberystwyth, I was caught in the eye by what struck me as a highly unusual cover for a 1938 edition of Anthony Hope’s fanciful pageturner The Prisoner of Zenda. Mind you, I’m not likely to turns those pages any time soon. I’m not one for Graustarkian excursions. That I found the old chestnut so arresting is due to the way in which it was sold anew to an audience of Britons to whom such a mode of escape from the crisis-ridden everyday must have been sufficiently attractive already. This was the 92nd impression of Zenda; and, with Europe at the brink of war, Ruritania must have sounded to those who prefer to face the future with their head in the hourglass contents of yesteryear like a travel deal too hard to resist.

Now, the publishers, Arrowsmith, weren’t taking any chances. Judging by the cover telling as much, they were looking for novel ways of repackaging a familiar volume that few British public and private libraries could have been wanting at the time.

British moviegoers had just seen Ruritania appear before their very eyes in the 1937 screen version of the romance, which make dashing Ronald Colman an obvious salesperson and accounts for his presence on the dust jacket. It is the line underneath, though, that made me look: “The Book of the Radio Broadcast,” the advertising slogan reads. Desperate, anachronistic, and now altogether unthinkable, these words reminded me just how far removed we are from those olden days when radio ruled the waves.

“The Prisoner of Zenda was recently the subject of a highly successful film,” the copy on the inside states somewhat pointlessly in the face of the faces on the cover. What’s more, it continues, a “further mark of its popularity” was the story’s “selection by the BBC as a radio serial broadcast on the National Programme.” To this day, the BBC produces and airs a great number of serial adaptations of classic, popular or just plain old literature; but, however reassuring this continuation of a once prominent storytelling tradition may be, a reminder of the fact that books are still turned into sound-only dramas would hardly sell copies these days. Radio still sells merchandise—but a line along the lines of “as heard on radio” is pretty much unheard of in advertising these days.

“This book is the original story on which the broadcast was based,” the dust jacket blurb concludes. I, for one, would have been more thrilled to get my hands or ears on the adaptation, considering that all we have left of much of the BBC’s output of aural drama is such ocular proof of radio’s diminished status and pop-cultural clout.

Perhaps, my enthusiasm at this find was too much tempered with the frustration and regret such a nostalgic tease provokes. At any rate, I very nearly left Ystwyth Books without the volume in my hands. That I walked off with it after all is owing to our friend, novelist Lynda Waterhouse, who saw me giving it the eye and made me a handsome present of it. And there it sits now on my bookshelf, a tattered metaphor of my existence: I am stuck in a past that was never mine to outlive, grasping at second-hand-me-downs and gasping for recycled air . . . a prisoner of a Zenda of my own unmaking.

Sweetness and The Eternal Light

My bookshelf, like my corporeal shell, has gotten heavier over the years. The display, like my waist, betrays a diet of nutritionally questionable comfort food—of sugar and spice and everything nice. Now, I won’t take this as an opportunity to ponder just what it is that I am made of; but those books sure speak volumes about the quality of my food for thought. There is All About Amos ‘n’ Andy (1929), The Story of Cheerio (1937), and Tony Wons’s Scrap Book (1930). There is Tune in Tomorrow (1968), the reminiscences of a daytime serial actress. There’s Laughter in the Air (1945) and Death at Broadcasting House (1934). There are a dozen or so anthologies of scripts for radio programs ranging from The Lone Ranger to Ma Perkins, from Duffy’s Tavern to The Shadow.

My excuse for my preoccupation with such post-popular culture, if justification were needed, has always been that there is nothing so light not to warrant reflection or reverie, that dismissing flavors and decrying a lack of taste is the routine operation of the insipid mind. That said, I am glad to have added—thanks to my better half, who also looks after my dietary needs—a book that makes my shelf figuratively weightier rather than merely literally so.

The book in question is The Eternal Light (1947), an anthology of twenty-six plays aired on that long-running program. It is a significant addition, indeed—historically, culturally, and radio dramatically speaking.

In the words of Louis Finkelstein, President of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, under whose auspices the series was produced, The Eternal Light was a synthesis of scholarship and artistry, designed to “translate ancient, abstract ideas into effective modern dramatics.”

In his introductory essay “Radio as a Medium of Drama,” Morton Wishengrad, the playwright of the series, defended broadcasting as a valuable if often misused “tool.” He did so at a time when, in the disconcerting newness of postwar opportunity and responsibility, radio was increasingly—and indiscriminately—dismissed as the playground of Hucksters, to name a bestselling novel of 1946 whose subject, like Herman Wouk’s Aurora Dawn (1947), was the prosperity and self-importance of the broadcasting industry in light of the perceived vacuity of its product.

“An automobile does not manufacture bank-robbers,” Wishengrad reasoned, “it transports them. It also transports clergymen. It is neither blameworthy because it does the first nor is it an instrument of piety because it does the latter. It is merely an automobile, a tool.

What the medium needed—and what the times required—were writers who had “something to say about the culture.”

According to Wishengrad, there was “nothing wrong” with the techniques of radio writing. He noted that serial drama, derided and reviled by “demonstrably incompetent” reviewers, had great storytelling potential: “Here are quarter-hour segments in the lives of people which could transfigure a part of each day with dramatic truth and an intimation of humanity instead of presenting as they now do a lolly-pop on the instalment plan.”

A “lolly-pop on the instalment plan”! To paraphrase Huckster author Frederic Wakeman’s parody of radio commercials: love that phrase. Wishengrad is one of a small number of American radio dramatists whose scripts remain memorable and compelling even in the absence of the actors and sound effects artist who interpreted them. Of the latter’s métier Wishengrad wrote: “Sound is like salt. A very little suffices.” He cautioned writers, in their “infatuation with its possibilities,” not to “drown” their scripts in aural effects.

Wishengrad’s advice to radio dramatists is as sound as his prose. “Good radio dialogue,” he held, should come across “like a pair of boxers trading blows, short, swift, muscular, monosyllabic.” Speeches, he cautioned, ought not to “be long because the ear does not remember. There is quick forgetfulness of everything except the last phrase or the last word spoken.”

While Wishengrad made no use of serialization in The Eternal Light—as much as the title suggests the continuation and open-endedness of the form—his scripts bear out what he imparts about style and live up to his insistence on substance.

Take “The Day of the Shadow,” for instance. Produced and broadcast over NBC stations on 18 November 1945, the play opens: “Listen. Listen to the silence. I have come from the land of the day of the shadow. I have seen the naked cities and the dead lips. Someone must speak of this. Someone must speak of the memory of things destroyed.”

The abstract gives way to the concrete, as the speaker introduces himself as the “Chaplain who stood before the crematorium of Belsen.”

I have buried 23,000 Jews. I have a right to speak. I stood the last month in Cracow when “Liberated” Jews were murdered. I have no pretty things to tell you. But I must tell you.

The “plain, and written down, and true” figures—appropriated from the “adding machines of the statisticians”—tell of the silenced. But, the Chaplain protests, “[l]et the adding machines be still,” and let the survivors—the yet dying—speak; not of the past but of the continuum of their plight, of the aftermath that comes after math has accounted for the eighty percent of Europe’s Jewish population who were denied outright the chance to make their lives count.

At the time The Eternal Light was published, radio drama, too, was dying; at least the drama with a purpose and a faith in the medium. To this date, it is a body unresuscitated; and what is remembered of it most is what is comforting rather than demanding, common rather than extraordinary. Shelving the candy, resisting the impulse to reach for the sweet and the obvious—the lolly-popular—I realize anew just what has been lost to us, what we have given up, what we have forgotten to demand or even to long for . . .

Listen, Learn, and Log

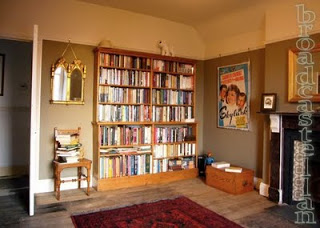

I am hardly the go-getter type. My goals are even more modest than my needs, which is to say that a full and fulfilling present day matters more to me than any future success for the prediction and preparation of which I lack the foresight. Among my few ambitions is it to amass volumes enough to have one of the most comprehensive private libraries devoted to turning the volume up—to American and, to a lesser degree, British radio and to the dramatics of the air in particular: published scripts, contemporary criticism, and latter-day assessments of the so-called “golden age” of radio.

I am hardly the go-getter type. My goals are even more modest than my needs, which is to say that a full and fulfilling present day matters more to me than any future success for the prediction and preparation of which I lack the foresight. Among my few ambitions is it to amass volumes enough to have one of the most comprehensive private libraries devoted to turning the volume up—to American and, to a lesser degree, British radio and to the dramatics of the air in particular: published scripts, contemporary criticism, and latter-day assessments of the so-called “golden age” of radio.

Until now, matters were complicated by the fact that I never had my own shelves on which to store such records of radio’s past. Well, I’ve got the bookshelves set up in my room at last. Nearly five months after moving into our new old house, I once again enjoy ready access to the appreciable if generally unappreciated literature of the air.

Back in November 1923, a critic of Radio Broadcast magazine observed that since libraries and radio have similar aims, it was

surprising that they have not cooperated nearly as fully as they might. Much of the radio broadcasting is instructive and entertaining; and so is it with the books on the library shelves. Radio is ever improving the musical and literary tastes of thousands of listeners-in, who, having their interest aroused, may find increased pleasure from music or literature—and the libraries can supply the latter.

Some twenty years later, what there was of radio literature hardly reflected the programs enjoyed by millions on radio. Calling it a “sad observation,” Sherman H. Dryer remarked in Radio in Wartime (1942) that

in the twenty-five years of its life few serious or critical books have been written about radio. The literature of radio is divided into two main parts: anthologies of “best” broadcasts, or vocational texts—How to Write for Radio, Radio Direction, How to Become an Announcer.

To these two kinds of books, Dryer—among a few others like Robert Landry, Francis Chase, and Charles Siepmann—added a small number of critical studies on radio broadcasting; and, two decades later, there emerged a market for nostalgia and history.

As Max J. Herzberg put it in Radio and English Teaching (1941), radio “need not be a substitute for the library; it can result in more and not less frequent use of books.”

I find that, tuning in, I not only turn to books on radio, but go in search of related material, original sources and histories. In other words, radio does not merely compel me to set up a shelf for books devoted to the subject; it continues to educate me about Western culture, the histories in which it dealt and out of which it arose. Looking at the faces of long forgotten performers and reading about their once famous acts tells me a lot about the boundaries and hazards of any pursuit of happiness defined by popularity and the statistical apparatus relied upon for its measurement.

The by now unpopular culture of radio dramatics has proven an academic and professional cul-de-sac for me; but my interest in and commitment to its study has remained nearly undiminished. As I said, I am not very ambitious—which is precisely why I feel free to continue the pursuit of what doesn’t seem to get me anywhere . . .

This, by the way, is my 701st entry into the broadcastellan journal.

They Also Sell Books: W-WOW! at Partners & Crime

Legend has it that, when asked what Cecil B. DeMille was doing for a living, his five-year-old grand-daughter replied: “He sells soap.” Back then, in 1944, the famous Hollywood director-producer was known to million of Americans as host and nominal producer of the Lux Radio Theater, from the squeaky clean boards of which venue he was heard slipping (or forcefully squeezing) many a none-too-subtle reference to the sponsor’s products into the behind-the-scenes addresses and rehearsed chats with Tinseltown’s luminaries, lines scripted for him by unsung writers selling out in the business of making radio sell.

No doubt, the program generated sizeable business for Lever Brothers; otherwise, the theatrical spin cycle conceived to bang the drum for those Lads of the Lather would not have stayed afloat for two decades, much to the delight of the great (and only proverbially) unwashed. For all its entertainment value, commercial radio was designed to hawk, peddle and tout; and although the spiel heard between the acts of wireless theatricals like Lux has long been superseded by the show and sell of television and the Internet, old radio programs still pay off, no matter how freely they are now shared on the web. In a manner of speaking, they still sell, albeit on a far smaller and downright intimate scale.

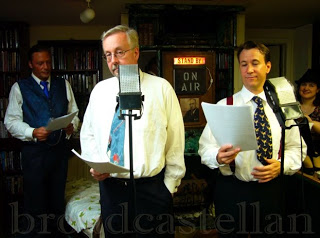

Take W-WOW! Radio. Now in its fourteenth season, the opening of which I attended last month, the W-WOW! Mystery Hour can be spent—heard and seen—on the first Saturday of every month (July and August excepting) from a glorified store room at the back of one of the few remaining independent and specialty booksellers in Manhattan: Partners & Crime down on Greenwich Avenue in the West Village. The commercials recited by the cast are by now the stuff of nostalgia, hilarity, and contention (“In a coast-to-coast test of hundreds of people who smoked only Camels for thirty days, noted throat specialists noted not one single case of throat irritation due to smoking Camels“); but the readings continue to draw prospective customers like myself.

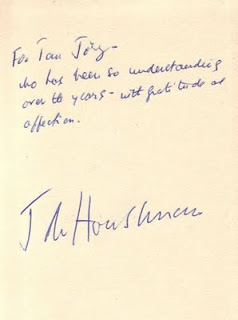

Whenever I am in town, I make a point of making a tour of those stores, even though said tour is getting shorter and more sentimental every year. There are rewards, nonetheless. Two of my latest acquisitions, Susan Ware’s 2005 “radio biography” of the shrewdly if winningly commercial Mary Margaret McBride and John Houseman’s 1972 autobiography Run-through (signed by the author, no less) were sitting on the shelves of Mercer Street Books (pictured) and brought home for about $8 apiece. The latter volume is likely to be of interest to anyone attending the W-WOW! production scheduled for this Saturday, 3 October, when the W-WOW! players are presenting the Mercury Theatre on the Air version of Dracula as adapted by none other than John Houseman.

As Houseman puts it, the Mercury’s “Dracula”—the series’s inaugural broadcast—is “not the corrupt movie version but the original Bram Stoker novel in its full Gothic horror.” Indeed, Houseman’s outstanding adaptation is a challenge worthy of W-WOW!’s voice talent and just the kind of material special effects artist DeLisa White (pictured above, on the right and to the back of those she so ably backs) will sink her teeth into, or whatever sharp and blunt instruments she has at her disposal to make your hair stand on end.

Rather more run-of-the-mill were the scripts chosen for W-WOW!’s September production, which, regrettably, was devoid of vamps. You know, those double-crossing, tough-talking dames that enliven tongue-in-cheek thrillers like The Saint (“Ladies Never Lie . . . Much” or “The Alive Dead Husband,” 7 January 1951) and Richard Diamond (“The Butcher Shop Case,” 7 March 1951 and 9 March 1952), a story penned by Blake “Pink Panther” Edwards and involving a protection racket. The former opened encouragingly, with a wife pretending to have killed a husband who turned out to be yet living, if not for long; but, as it turned out, the dame had less lines than any of the ladies currently in prime time, or any other time for that matter. Sure, crime paid on the air; but sex, or any vague promise of same, sells even better.

That said, I still walked out of Partners & Crime with a book in my hand. As I passed through the store on my way out, an out-of-print copy of A Shot in the Arm caught my eye and refused to let go. Subtitled “Death at the BBC,” John Sherwood’s 1982 mystery novel, set in Broadcasting House anno 1937 and featuring Lord Reith, the dictatorial Baron who ran the place, is just the kind of stuff I am so readily sold on, as I am on browsing in whatever bookstores are still standing offline—if only to give those who are still in the business of vending rare volumes a much-deserved shot in the open and outstretched arm.

Related recordings

“Ladies Never Lie . . . Much,” The Saint (7 January 1951)

“The Butcher Case,” Richard Diamond (7 January 1950)

“The Butcher Case,” Richard Diamond (9 March 1951)

“. . . reduced, blended, modernised”: The Wireless Reconstitution of Printed Matter

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

Gone were the days when a teenager like Mary Jones, whose story I encountered on a trip to the Welsh town of Bala last weekend, walked twenty-five miles, barefooted, for the privilege of owning a Bible. Sure, I enjoy the occasional daytrip to Hay-on-Wye, the renowned “Town of Books” near the English border where, earlier this month, I snatched up a copy of the BBC’s 1952 Year Book (pictured). Still, ever since the time of the great Victorian novelists, the reading public has been walking no further than the local lending library or wherever periodicals were sold to catch up on the latest fictions and follow the exploits of heroines like Becky Sharp in monthly installments.

In Victorian times, the demand for stories was so great that poorly paid writers were expected to churn them out with ever greater rapidity, which left those associated with the literary trade to ponder new ways of meeting the supply. In Gissing’s New Grub Street (1891), a young woman assisting her scholarly papa is startled by an

advertisement in the newspaper, headed “Literary Machine”; had it then been invented at last, some automaton to [. . .] turn out books and articles? Alas! The machine was only one for holding volumes conveniently, that the work of literary manufacture might be physically lightened. But surely before long some Edison would make the true automaton; the problem must be comparatively such a simple one. Only to throw in a given number of old books, and have them reduced, blended, modernised into a single one for today’s consumption.

Barbara Cartland notwithstanding, such a “true automaton” has not yet hit the market; but the recycling of old stories for a modern audience had already become a veritable industry by the beginning of the second quarter of the 20th century, during which “golden age” the wireless served as both home theater and ersatz library for the entertainment and distraction craving multitudes.

A medium of—and only potentially for—modernity, radio has always culled much of its material from the past, “Return with us now” being one of the phrases most associated with aural storytelling. It is a phenomenon that led me to write my doctoral study Etherized Victorians, in which I relate the demise of American radio dramatics to the failure to establish or encourage its own, autochthonous, that is, strictly aural life form.

Sure, the works of Victorian authors are in the public domain; as such, they are cheap, plentiful, and, which is convenient as well, fairly innocuous. And yet, for reasons other than economics, they strike us as radiogenic. Like the train whistle of the horse-drawn carriage, they seem to be the very stuff of radio—a medium that was quaint and antiquated from the onset, when television was announced as being “just around the corner.”

Perhaps, the followers of Becky Sharp should not toss out their books yet; as American radio playwright Robert Lewis Shayon pointed out, the business of adaptation is fraught with “artistic problems and dangers.” He argued that he “would rather be briefed on a novel’s outline, told something about its untransferable qualities, and have one scene accurately and fully done than be given a fast, ragged, frustrating whirl down plot-skeleton alley.”

It was precisely for this circumscribed path, though, that American handbooks like James Whipple’s How to Write for Radio (1938) or Josephina Niggli’s Pointers on Radio Writing (1946) prepared prospective adapters, reminding them that, for the sake of action, they needed to “retain just sufficient characters and situations to present the skeleton plot” and that they could not “afford to waste even thirty seconds on beautiful descriptive passages.”

As I pointed out in Etherized, broadcast writers were advised to “free [themselves] first from the enchantment of the author’s style” and to “outline the action from memory.” Illustrating the technique, Niggli reduced Jane Eyre—one of the most frequently radio-readied narratives—to a number of plot points, “bald statements” designed to “eliminate the non-essential.” Only the dialogue of the original text was to be restored whenever possible, although here, too, paraphrases were generally required to clarify action or to shorten scenes. Indeed, as Waldo Abbot’s Handbook of Broadcasting (1941) recommended, dialogue had to be “invented to take care of essential description.”

To this day, radio dramatics in Britain, where non-visual broadcasting has remained a viable means of telling stories, the BBC relies on 19th-century classics to fill much of its schedule. The detective stories of Conan Doyle aside, BBC Radio 7 has just presented adaptations of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847-48), featuring the aforementioned Ms. Sharp, and currently reruns Trollope’s Barchester Chronicles (1855-67). The skeletons are rather more complete, though, as both novels were radio-dramatized in twenty installments, and, in the case of Trollope’s six-novel series, in hour-long parts.

BBC Radio 4, meanwhile, has recently aired serializations of Trollope’s Orley Farm (1862), Wilkie Collins’s Armadale (1866) and Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862). Next week, it is presenting both Charlotte Brontë’s Villette and Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth (both 1853), the former in ten fifteen minute chapters, the latter in three hour-long parts.

Radio playwright True Boardman once complained that adaptations for the aural medium bear as close a relation to the original as “powdered milk does to the stuff that comes out of cows.” They are culture reconstituted. “[R]educed, blended, [and] modernised“, they don’t get a chance to curdle . . .

Note: Etherised Victorians was itself ‘reduced and blended,’ and published as Immaterial Culture in 2013.

Related writings (on Victorian literature, culture and their recycling)

“Hattie Tatty Coram Girl: A Casting Note on the BBC’s Little Dorrit”

“Valentine Vox Pop; or, Revisiting the Un-Classics”

“Curtains Up and ‘Down the Wires'”

“Eyrebrushing: The BBC’s Dull New Copy of Charlotte Brontë’s Bold Portrait”

So to Speke

When not at work on our new old house—where the floorboards are up in anticipation of central heating—we are on the road and down narrow country lanes to get our calloused hands on the pieces of antique furniture that we acquired, in 21st-century style, by way of online auction. In order to create the illusion that we are getting out of the house, rather than just something into it, and to put our own restoration project into a perspective from which it looks more dollhouse than madhouse, we make stopovers at nearby National Trust properties like Chirk Castle or Speke Hall.

The latter (pictured here) is a Tudor mansion that, like some superannuated craft, sits sidelined along Liverpool’s John Lennon Airport, formerly known as RAF Speke. The architecture of the Hall, from the openings under the eaves that allowed those within to spy on the potentially hostile droppers-in without to the hole into which a Catholic priest could be lowered to escape Protestant persecution, bespeaks a history of keeping mum.

Situated though it is far from Speke, and being fictional besides, what came to mind was Audley Court, a mystery house with a Tudor past and Victorian interior that served as the setting of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s sensational crime novel Lady Audley’s Secret. The hugely popular thriller was first serialized beginning in 1861 and subsequently adapted for the stage. Resuscitated for a ten-part serial currently aired on BBC Radio 4, the eponymous “lady”—a gold digger, bigamist, and arsonist whose ambitions are famously diagnosed as the mark of “latent insanity”—can now be eavesdropped on as she, sounding rather more demure than she appeared to my mind’s ear when reading the novel, attempts to keep up appearances, even if it means having to make her first husband, a gold digger in his own right, disappear down a well.

As if the house, Audley Court, did not have a checkered past of its own—

a house in which you incontinently lost yourself if ever you were so rash as to attempt to penetrate its mysteries alone; a house in which no one room had any sympathy with another, every chamber running off at a tangent into an inner chamber, and through that down some narrow staircase leading to a door which, in its turn, led back into that very part of the house from which you thought yourself the furthest; a house that could never have been planned by any mortal architect, but must have been the handiwork of that good old builder, Time, who, adding a room one year, and knocking down a room another year, [ … ] had contrived, in some eleven centuries, to run up such a mansion as was not elsewhere to be met with throughout the county […].

“Of course,” the narrator insists,

in such a house there were secret chambers; the little daughter of the present owner, Sir Michael Audley, had fallen by accident upon the discovery of one. A board had rattled under her feet in the great nursery where she played, and on attention being drawn to it, it was found to be loose, and so removed, revealed a ladder, leading to a hiding-place between the floor of the nursery and the ceiling of the room below—a hiding-place so small that he who had hid there must have crouched on his hands and knees or lain at full length, and yet large enough to contain a quaint old carved oak chest, half filled with priests’ vestments, which had been hidden away, no doubt, in those cruel days when the life of a man was in danger if he was discovered to have harbored a Roman Catholic priest, or to have mass said in his house.

Loose floorboards we’ve got plenty in our own domicile, and room enough for a holy manhole below. It being a late-Victorian townhouse, though, the hidden story we laid bare is that of the upstairs-downstairs variety. At the back, in the part of the house where the servants labored and lived, there once was a separate staircase, long since dismantled. It was by way of those steep steps that the maid, having performed her chores out of the family’s sight and earshot, withdrew, latently insane or otherwise, into the modest quarters allotted to her.

I wonder whether she read Lady Audley’s Secret, if indeed she found time to read at all, and whether she read it as a cautionary tale or an inspirational one—as the story of a woman who dared to rewrite her own destiny:

No more dependency, no more drudgery, no more humiliations,” Lucy exclaimed secretly, “every trace of the old life melted away—every clue to identity buried and forgotten—except […]

… that wedding ring, wrapped in paper. It’s enough to make a priest turn in his hole.

Together . . . to Gaza? The Media and the Worthy Cause

The British Broadcasting Corporation has had its share of problems lately, what with its use of licensee fees to indulge celebrity clowns in their juvenile follies. Now, the BBC, which is a non-profit public service broadcaster established by Royal Charter, is coming under attack for what the paying multitudes do not get to see and hear, specifically for its refusal to broadcast a Disasters Emergency Committee appeal for aid to Gaza. According to the BBC, the decision was made to “avoid any risk of compromising public confidence in the BBC’s impartiality in the context of an ongoing news story.” To be sure, if the story were not “ongoing,” the need for financial support could hardly be argued to be quite as pressing.

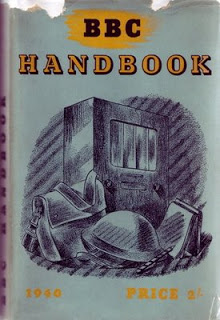

In its long history, the BBC has often made its facilities available for the making of appeals and thereby assisted in the raising of funds for causes deemed worthy by those who approached the microphone for that purpose. Indeed, BBC radio used to schedule weekly “Good Cause” broadcasts to create or increase public awareness of crises big and small. Listener pledges were duly recorded in the annual BBC Handbook.

From the 1940 edition I glean, for instance, that on this day, 29 January, in 1939, two “scholars” raised the amount of £1,310 for a London orphanage. Later that year, an “unknown cripple” raised £768, while singer-comedienne Gracie Fields’s speech on behalf of the Manchester Royal Infirmary brought in £2,315. The pleas were not all in the name of infants and invalids, either. The Student Movement House generated funds by using BBC microphones, as did the Hedingham Scout Training Scheme.

While money for Gaza remains unraised, the decision not to get involved in the conflict raises questions as to the role of the BBC, its ethics, and its ostensible partiality. Just what constitutes a “worthy” cause? Does the support for the civilian casualties of war signal an endorsement of the government of the nation at war? Is it possible to separate humanitarian aid from politics?

It strikes me that the attempt to staying well out of it is going to influence history as much as it would to make airtime available for an appeal. In other words, the saving of lives need not be hindered by the pledged commitment to report news rather than make it.

Impartiality and service in the public interest were principles to which the US networks were expected to adhere as well, however different their operations were from those of the BBC. In 1941, the FCC prohibited a station or network from speaking “in its own person,” from editorializing, e.g. urging voters to support a particular Presidential candidate; it ruled that “the broadcaster cannot be an advocate”; but this did not mean that airtime, which could be bought to advertise wares and services, could not be purchased as well for the promotion of ideas, ideals, and ideologies.

The broadcasting of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats or his public addresses on behalf of the March of Dimes and the War Loan Drives did not imply the broadcasters’ favoring of the man or the cause.

On this day in 1944, all four major networks allotted time for the special America Salutes the President’s Birthday. Never mind that it was not even FDR’s birthday until a day later. The cause was the fight against infantile paralysis; but that did not prevent Bob Hope from making a few jokes at the expense of the Republicans, who, he quipped, had all “mailed their dimes to President Roosevelt in Washington. It’s the only chance they get to see any change in the White House.”

A little change can bring about big changes; but, as a result of the BBC’s position on “impartiality,” much of that change seems to remain in the pockets of the public it presumes to inform rather than influence.

Related writings

Go Tell Auntie: Listener Complaints Create Drama at BBC

Election Day Special: Could This Hollywood Heavy Push You to the Polls?

" . . . within the limits": Radio and the Code

“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day, 12 January 1941, Seymour talked to announcer Graham McNamee about her experience entering the broadcasting business in the mid-1920s, back when it bore little resemblance to the confident, respected, and efficient medium it had become by the late 1930s, by which time Seymour had co-written another book on Practical Radio Writing.

“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day, 12 January 1941, Seymour talked to announcer Graham McNamee about her experience entering the broadcasting business in the mid-1920s, back when it bore little resemblance to the confident, respected, and efficient medium it had become by the late 1930s, by which time Seymour had co-written another book on Practical Radio Writing.

Many such how-to guides followed throughout the 1940s, a testament to the vastness of the industry, its demand for written words and for talent familiar with the codes and regulations to which they were expected to adhere. In the 1920s, when Seymour tried to promote herself from typist to writer, she was told by her boss at WEAF, New York, that “no radio station will ever need more than one script writer,” to which shortsighted remark McNamee, himself one of the old-timers, responded with a resounding “Wow!”

The days of largely unchecked improvisation were over. Being obliged to keep their word, broadcasters had learned that the spoken word needed to become copy (that is, text) and that every dramatic dialogue had to be played by the book the FCC would otherwise throw at them.

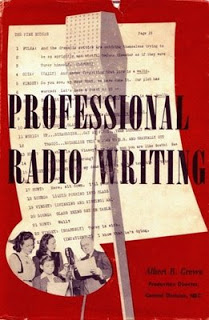

One of the latest addition to my library, Albert R. Crews’s Professional Radio Writing (1946), acquainted readers with what was known as the NAB code. As the author, then production director at NBC, explained, the code was a measure of self-censorship undertaken by the National Association of Broadcasters and adopted on 11 July 1939 to outline the “handling of children’s programming, controversial public issues, educational programming, news, [and] religious broadcasts,” as well as to set down the “acceptable length of commercial copy and its content.”

In keeping with this code, the National Broadcasting Company developed its own guidelines for “continuity acceptance,” “continuity” being anything read on the air. Anyone learning how to write radio drama with the view of hearing it produced had to keep in mind, for instance, that “[w]hite slavery, sex perversion or the implication of it may not be treated in NBC programs” and that the “fact of marriage must never be used for the introduction of scenes of passion excessive or lustful in character, or which are clearly unessential to the plot development.”

In the treatment of crime, the “use of horrifying sound effects as such” was “forbidden.” According to the code, no character was to “be depicted in death agonies,” nor could the “death of any character be presented in any manner shocking to the sensibilities of the public.” The very “mention of intoxicants” had to “be held to a minimum” and “suggestive dialogue and double meaning” was “never [to] be used.”

Responding to the hullaballoo over CBS’s “War of the Worlds” broadcast, NBC also stipulated that

[f]ictional events shall not be presented in the form of authentic news announcements. Likewise, no program or commercial announcement will be allowed to be presented as a news broadcast using sound effects and terminology associated with news broadcasts. For example, the use of the word “Flash!” is reserved for the announcement of special news bulletins exclusively, and may not be used for any other purpose except in rare cases where by reason of the manner in which it is used no possible confusion may result.

Was it any wonder that, as Crews put it, there had been a “tendency on the part of many outstanding writers in [the US] to scoff at radio as a possible medium for their talents”? Such talent-repelling strictures notwithstanding, he found it “heartening” to note just

how many writers of importance radio has itself created. There are dozens of highly skilled dramatic writers who are, for the most part, completely unknown to the public, but who each day do distinguished work in their field. The anonymity of such writers is no measure of their skill or their success.

It is with the efforts of those mostly unheard of and almost entirely forgotten writers that I shall continue to concern myself in this journal; writers who skillfully interpreted the code and somehow managed to subvert it, or who at least found leeway for play “within the limits” set down for them; writers whose works, to take up one of Seymour’s questions, have endured in recordings even if American radio drama, as an art, has largely ceased to develop further.

Having lost their purpose as instruction manuals for an essentially defunct business, books like Professional Radio Writing nonetheless instruct us how to read the plays that went on the air, to account for their limitations and appreciate their qualities.

Let George Say It

I penned my first autobiography at the age of sixteen. With the bombast befitting an insecure teenager eager for validation, I called it a “memoir.” It was a short, handwritten volume I passed around to fellow students, a performance designed at once to justify, expose, and invent myself. Like so many pieces of juvenilia, those “memoirs” were destroyed in an act of reinvention, or, not to be fanciful, embarrassment. I fear that many of the instances I recorded, however embellished, edited or carefully selected my memories, may be far more difficult to recreate, faded as my recollections have during all those intervening years that have made me a stranger to my former selves. I seem to have made forgetting a virtue by looking at it as the ability to move on and start over as if from scratch.

I penned my first autobiography at the age of sixteen. With the bombast befitting an insecure teenager eager for validation, I called it a “memoir.” It was a short, handwritten volume I passed around to fellow students, a performance designed at once to justify, expose, and invent myself. Like so many pieces of juvenilia, those “memoirs” were destroyed in an act of reinvention, or, not to be fanciful, embarrassment. I fear that many of the instances I recorded, however embellished, edited or carefully selected my memories, may be far more difficult to recreate, faded as my recollections have during all those intervening years that have made me a stranger to my former selves. I seem to have made forgetting a virtue by looking at it as the ability to move on and start over as if from scratch.

Perhaps, one reason for my dwelling in and on the presumably out-of-date in a journal reflective of my readings, viewings, and listening experiences is that it allows me to discover myself in a researchable past other than that which is chronologically and biologically my own: movies, radio programs, books that precede my past and inform my present. To research my story, I must rely on a memory I dare not trust. When it comes to my early life, I have little to go on, other than flashes of dreamlike recollections.

One of the problems involving the autobiographical act is to arrive at a narrative frame that fits the picture without distorting, let alone creating, it. It is difficult to determine where an autobiography ought to end, considering that, as its writer, one is still in engaged in the creation of memories. One is alive and, apparently, compelled to prove it. A future event might call for an entirely new arrangement of facts—a life-changing event may lie ahead, rendering negligible much that seems important at present.

Not quite as problematic, but troublesome nonetheless, is the beginning. Does one begin with one’s family, with one’s ancestors, with a description of the birthplace that, presumably, shaped our early life? Should an autobiography start with an explanation, an apology for the hubris of taking oneself serious enough to warrant such a performance, or an acknowledgement of whomever we construe as our audience? Dear reader, is this my life? Should, as in James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist, the voice reflect the age, mind and intellect of the subject, the self turned object, in various stages of existence?

One man who knew how to begin was the aforementioned Emlyn Williams, born on this day, 26 November, in 1905; he grew up in a remote town in Wales, his parents hardly proficient in English, to become a well-known actor and playwright (a production of whose Night Must Fall I briefly discussed here), personae or roles that no doubt influenced his performance and may well have created the impetus to for it. He could count on an audience, a public that presumed and demanded to know him.

Williams’s lyrical introduction to George: An Early Autobiography (1961) is one that compels me both to read on and revisit the idea of writing my own life. Aware of the task at hand, of the challenges of starting, of devising a beginning reflective of one’s own start in life and the impossibilities of doing so ab ovo, it is disarmingly reflective:

The world was waiting. Waiting for me, to whisper my incantations. “I am George Emlyn Williams and . . .” I was lying with my head on my fist on morning grass, dry of dew and warm with the first heat of the year. All was still, even the stalks clutched in my hot fingers. I had come up into the fields to gather shaking-grass, a week with a hundred beads tremulous to the touch, which my mother would inter in two vases where it would frugally desiccate and gather dust forever. Spring smells and earth feelings crept into my seven-year-old boy; nine-tenths innocent, one-tenth conscient, it responded. I rolled one cheek up till it closed an eye, and squinted down at the sunlit village. A dog lay asleep in the road. Mrs. Jones South Africa was hanging washing, and quavering a hymn. Cassie hung on their gate and called for Ifor. “Time to go to the well!” The bleat of a sheep. A bird called, careless, mindless. Eighteen inches from my eye, a tawny baby frog was about to leap. It waited.

Everything waited: the hymn had ceased, the bird was dumb and suspended. “I was born November the 26th 1905 and the world was completed at midnight on Saturday July the 10th 4004—our Bible stated the year at the top of page one, the rest I felt free to add—“and has been going ever since, through Genesis Revelation the six wives of Henry the Eighth the Guillotine and the Diamond Jubilee right until this minute 10 AM. Sunday April the 14th 1912, when the world has stopped. The sun will not set tonight, or ever again, and I am the only one who knows.”

No sound: the spool of time has run down, the century is nipped in the bud. I shall never grow up, or old, but shall lie on the grass forever, a mummy of a boy with nestling in the middle of it a nameless warmth like the slow heat inside straw. This is the eternal morning.

The frog jumped. Cassie called again. I scrambled up, brushed my best knickerbockers, pulled the black stockings up inside them, raced down and hopped between my water buckets into the wooden square which kept them well apart so as not to splash. The sun did set, and by the time it rose next morning the Titanic had been sunk. If the world had stopped, they would not have drowned; I thought about it for a day.

The century, un-nipped, has crept forward, and the knickerbockers are no more. They encased one brother till he burst out of them, then another till they fell exhausted away from him, turned into floor rags and at last were decently burned. But I am still here, not yet decently burned or a floor rag or even exhausted, George Emlyn Williams, born November the 26th, 1905.

Autobiographies are performances, to be sure; but the audience, however large, also includes the one in the scrutinizing self in the mirror. Staring at it, it gives me no hints as to how, or whether, to write one. Regardless of all the personal reflections I have offered in this journal, I no longer have the confidence, or the illusions, of a sixteen year old who presumes that his life matters; nor is mine the life of a man like Emlyn Williams, who did.