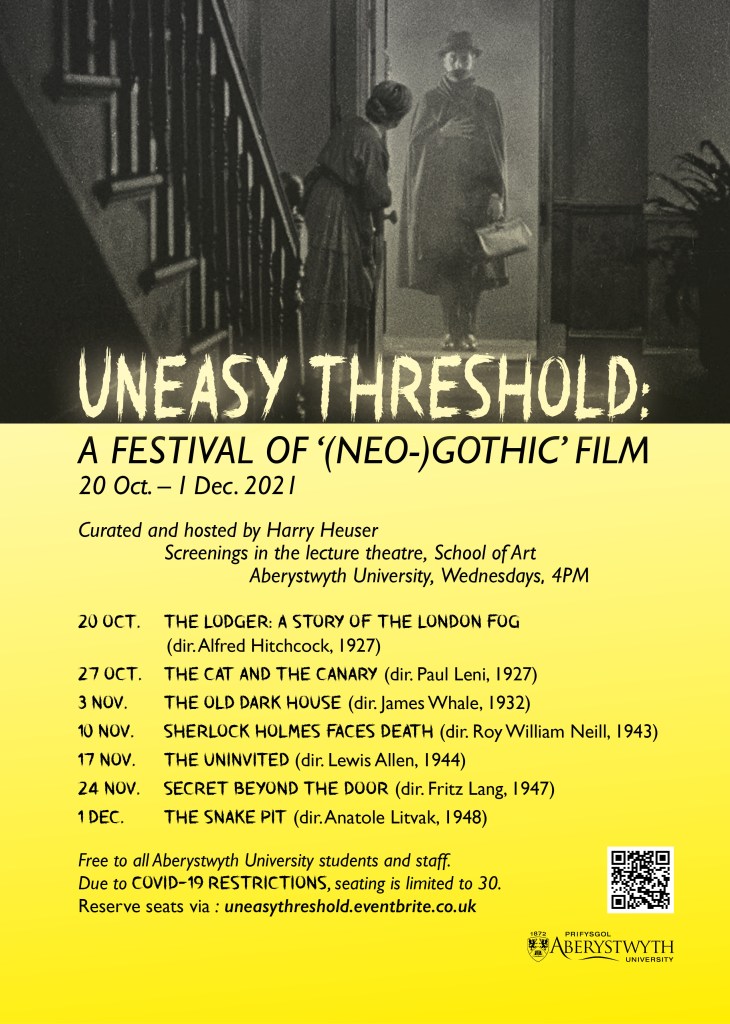

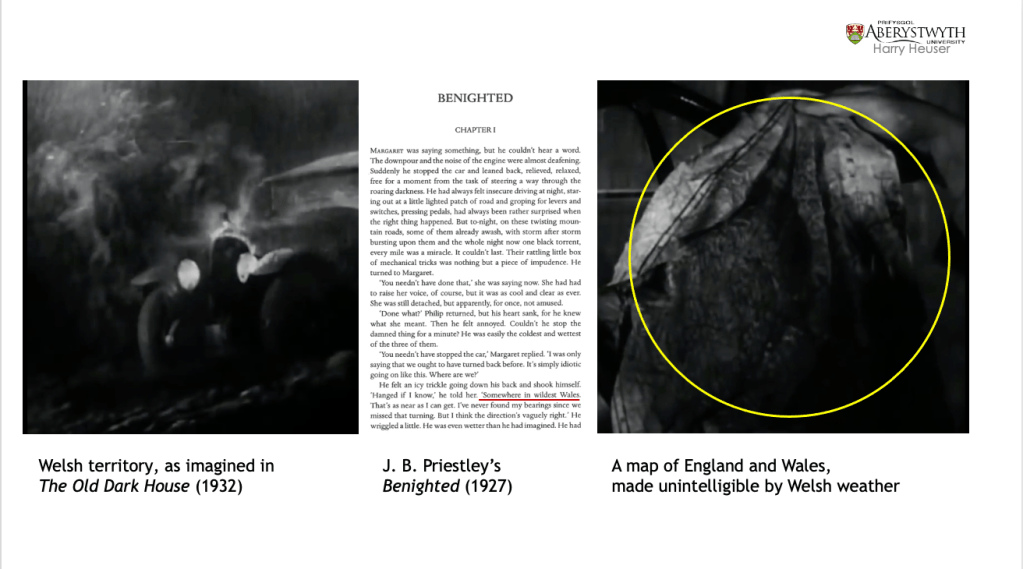

Much has been said about the titular edifice of Universal Studio’s 1932 melodrama The Old Dark House, the third in the series of films I am screening as part of my Gothic Imagination module at Aberystwyth University. Directed by the queer English Great War veteran James Whale, and adapted from J. B. Priestley’s 1927 novel Benighted, The Old Dark House is often argued to be a commentary on Imperial Britain during the so-called interwar years (that is, the period between the two World Wars, Britain having been involved in plenty of other international conflicts besides): an ancient but crumbling family home – run by aging and morally corrupt imbeciles and cut off from the world by water. It has been called, more than once, a “metaphor for … England.”

And yet, the story is not set England but in Wales, and the novel and film alike exploit and perpetuate the stereotypes of what, presumably, constitutes Wales and sets it apart from neighboring England: the wild, the uncivilised, the superstitious and unenlightened. Wales, according to Priestley and Whale, is gothic territory. It is the stuff of romance – or the English definition of romance – meaning that when the English want to go primitive, they think Wales.

Here is what the dreamer Penderel, himself a war veteran, says about Wales as he is being driven around in his friend’s motorcar one dark and dismal night:

I don’t want to go to Shrewsbury. I don’t particularly want to go anywhere. Something might happen here, and nothing ever happens in Shrewsbury, and nothing much on the other side of Shrewsbury. But here there’s always a chance.

The Hollywood ending aside, the film is remarkably faithful to the novel, retaining much of Priestley’s dialogue. While I am not sure just how many US American viewers back then would have understood the reference to the border that Shrewsbury represents, both Priestley and Whale would have known that, when the name “Shrewsbury” is dropped, the meaning “borderline” is implied. Arriving at Shrewsbury – and this is the party’s intention – means traversing the Welsh Bridge over the Severn and arriving back in England.

The party in question – Penderel and his friends, the married and bickering couple Margaret and Philip – has lost its way in what Priestley lets Philip describe as “wildest Wales.” The colonial attitudes toward Wales as both enchanted and benighted – as a place where there is ‘always a chance’ – the chance of an improvement in infrastructure excepting – are at the heart of this modally gothic narrative.

When the drunkard Welsh butler Morgan opens the door upon their unannounced arrival, he “produce[s] from somewhere at the back of his throat, a queer gurgling sound” that Penderel cannot translate. Priestley tells us that “Penderel knew no Welsh.” And yet, he says with confidence, in the book and film version alike, that “Even Welsh out not to sound like that; it was as if a lump of earth had tried to make a remark.”

Wales, to be sure, was just that to England, or many in England, a mute lump of Earth to be exploited for its resources. It is not Wales that is gothic – or Gothic – but the perspective of the English that, fascinating as they may be with the wildness of Wales – impose their views on the nation they invade like “travellers in a foreign country,” as Priestley has Penderel see it.

Morgan, as we soon learn, cannot communicate in any spoken language. He is a personification of Wales infantilised, gesturing like “some prehistoric monster.” Wales, the source of mined ore – of coal and slate and lead, silver and gold – as well as Water, was often seen as little more than potential to be unearthed and funnelled for the benefit of England. The tradition was deemed to be expendable.

In The Old Dark House, as in Benighted, the nightmare vision makes way for daylight. What we experienced was a Phantasmagoria staged by the visiting English. The travelers depart, whether enlightened by what they experienced or just glad to have survived it. The perspective of the hosts is not considered.

Hollywood would return to a fairy-tale Wales in The Wolf Man a decade later, in which Welsh landscape and culture, rendered unrecognisable, become the other when England was seen as the real, the upholder of values, in its fight against fascism. To this day, visitors prefer to be enchanted by Wales, an old dark house whose perceived darkness is to a large extent a product of an English or Anglo-American imagination.