“Poor print.” That was all I had to say after attending a screening of Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari (1920) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. I was dreadfully disappointed. It felt like walking through an exhibition of Expressionist art in which all the paintings were covered in plastic, the lights dimmed, and the space brightened only by an occasional flash of a camera. I pretty much had the same impression when, preparing for a trip to Prague, I tried to take in Der Golem by exposing myself to the horrors of a cheap copy I had dug out of a bargain bin at a third-rate department store. You might as well experience these films on the radio, where the visuals are as clear and bold as you can make them, provided your mental camera is both creative and focused enough to take pictures that are worth keeping.

“Poor print.” That was all I had to say after attending a screening of Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari (1920) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. I was dreadfully disappointed. It felt like walking through an exhibition of Expressionist art in which all the paintings were covered in plastic, the lights dimmed, and the space brightened only by an occasional flash of a camera. I pretty much had the same impression when, preparing for a trip to Prague, I tried to take in Der Golem by exposing myself to the horrors of a cheap copy I had dug out of a bargain bin at a third-rate department store. You might as well experience these films on the radio, where the visuals are as clear and bold as you can make them, provided your mental camera is both creative and focused enough to take pictures that are worth keeping.

Tonight, BBC Radio 3 attempted no less with “Caligari,” a radio adaptation of Robert Wiene’s seminal horror film, one of the few classics of the cinema to rank among the top 250 films on the Internet Movie Database. In the exposition, poet/playwright Amanda Dalton slyly comments on the challenges of such a project. “Caligari” opens with the sound of a board (an advertisement for the fair, a title card for the film, a piece of scenery) being painted and hammered into position. The question this gesture begs is whether the brush and the hammer are being passed on to us. Are we the artist, the audience, or the subject? Can we choose? Must we?

A “strangely arresting” film that succeeds in giving “pictorial interpretation to a madman’s vision,” one early commentator (Carlyle Ellis) said of Caligari. Such a statement drives home that Caligari is itself an exercise in translation: a bringing to light and darkness the workings of a crooked, crazy mind in crooked, crazy images. Rather than a translation, then, Dalton’s “Caligari” (available online until 2 November 2008) should be performing nothing more—and nothing less—than a transplant, a projection of a madman’s vision onto the screen of our own mental theater, sound or otherwise.

By installing a narrator at the changing scene, “Caligari” insists on translating and interpreting, at times so facetiously as to undermine any sense of terror. Irritation, perhaps, but not anxiety. More clamorous and voluble than radio needs to be, Dalton’s frantic, play, whose light-heartedness is weighed down by anachronistic cliches like “over my dead body,” is, for all its irreverence, an unsatisfactorily literal transliteration. Too many voices shouting down our imagination, “Caligari” reviews familiar images it does not permit our mind’s eye to see, let alone re-envision or remake. A running commentary on the original on a familiarity with which it depends, “Caligari” plays itself out as a series of aural footnotes.

Last Friday, during an ostensible lecture on German film prior to a screening of Germany’s latest cinematic export, Die Welle (2008), I once again caught glimpses of Wiene’s seminal work; but its images were taken out of a context that the dull, rambling talk could not create. I had a similar attitude toward Dalton’s adaptations.

A few bars of the German national anthem, as it was once sung (that is, including the first stanza, “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles”), can hardly suffice in assisting us to adopt a Weimar Republican mindset; nor can mentions of an “intricate design” recreate an expressionistic set. And while a babble of tongues may make a failed democratic system audible, “Caligari” is little more than a poor substitute for the experience of either art or history.

Meanwhile, I am sure that the jack-o’-lantern I carved today (and display above) would look better on the air or in anyone’s mind, especially now that Montague, our terrier, has already begun to disfigure it. Is he adopting traits you may have decided to attribute to me?

Placing Mitchell Leisen alongside Hollywood’s top flight directors is likely to raise eyebrows among those whose brows are already well elevated. Most others will simply shrug their cold shoulders in“Who he? indifference, a stance with which I, whose shoulders are wont to brush against the dusty shelves and musty vaults of popular culture, am thoroughly familiar by now. Respected for his knack of striking box-office gold but dismissed by his peers, the former art director was not among the auteurs whose works are read as art chiefly because it is easier to conceive of artistic expression as a non-collective achievement: something that bears the clearly distinguishable signature of a single individual. Their careful design aside, little seems to bespeak the Leisen touch, which is as light as it is assured. Stylish and slick in the best Paramount tradition, a Leisen picture stunningly sets the stage under the pretense of drama; otherwise, it has few pretensions.

Placing Mitchell Leisen alongside Hollywood’s top flight directors is likely to raise eyebrows among those whose brows are already well elevated. Most others will simply shrug their cold shoulders in“Who he? indifference, a stance with which I, whose shoulders are wont to brush against the dusty shelves and musty vaults of popular culture, am thoroughly familiar by now. Respected for his knack of striking box-office gold but dismissed by his peers, the former art director was not among the auteurs whose works are read as art chiefly because it is easier to conceive of artistic expression as a non-collective achievement: something that bears the clearly distinguishable signature of a single individual. Their careful design aside, little seems to bespeak the Leisen touch, which is as light as it is assured. Stylish and slick in the best Paramount tradition, a Leisen picture stunningly sets the stage under the pretense of drama; otherwise, it has few pretensions. Leisen was not about to denounce the medium he had romanced in two of his earlier revues, The Big Broadcast of 1937 and its 1938 follow-up. Instead, Golden Earrings confronts nationalistic, state-run radio with a distinctly American voice of commercial broadcasting. In the narrative frame, the English officer is seen relating his story to Quentin Reynolds (pictured here with Milland), a news commentator known for his on-air missives to Doktor Goebbels and Herr Schickelgruber.

Leisen was not about to denounce the medium he had romanced in two of his earlier revues, The Big Broadcast of 1937 and its 1938 follow-up. Instead, Golden Earrings confronts nationalistic, state-run radio with a distinctly American voice of commercial broadcasting. In the narrative frame, the English officer is seen relating his story to Quentin Reynolds (pictured here with Milland), a news commentator known for his on-air missives to Doktor Goebbels and Herr Schickelgruber. “Enjoy the movie.” That is the response we get when we tell friends and acquaintances that we are on our way to the cinema. And while it is true that we generally seek enjoyment, whether by looking at separated lovers or severed heads, movie-going can be a disconcerting, unsettling event well beyond the shocks and jolts provided by horror and romance. The Boy with the Striped Pyjamas (a British film in its British spelling), is likely to be such an experience to anyone with a pulse and a sense of humanity ready for the tapping. To me, it was nothing short of devastating. I am not resorting to hyperbole when I say that I was rendered speechless; those accompanying me can attest to my disquietude. It has been a decade since last I watched a film (Saving Private Ryan) that has stirred and traumatized me to such a degree that, coming out of the theater, I felt sick to my stomach. No wonder. I had just been coerced into walking straight into the gas chamber of a concentration camp.

“Enjoy the movie.” That is the response we get when we tell friends and acquaintances that we are on our way to the cinema. And while it is true that we generally seek enjoyment, whether by looking at separated lovers or severed heads, movie-going can be a disconcerting, unsettling event well beyond the shocks and jolts provided by horror and romance. The Boy with the Striped Pyjamas (a British film in its British spelling), is likely to be such an experience to anyone with a pulse and a sense of humanity ready for the tapping. To me, it was nothing short of devastating. I am not resorting to hyperbole when I say that I was rendered speechless; those accompanying me can attest to my disquietude. It has been a decade since last I watched a film (Saving Private Ryan) that has stirred and traumatized me to such a degree that, coming out of the theater, I felt sick to my stomach. No wonder. I had just been coerced into walking straight into the gas chamber of a concentration camp.

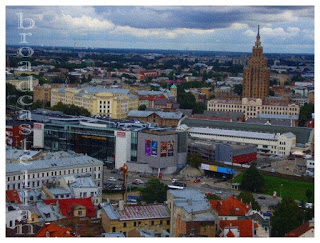

The Latvian National Opera had not yet reopened for the fall season. Little more could be said in our defense. Having enjoyed another organ concert in the Dome, followed by a Russian meal at Arbat, we once again made our way through the old town to pay a visit to the city’s Forum Cinemas, a multiplex boasting the largest screen in Northern Europe. By the end of our stay, we had pretty much exhausted its late-night offerings (the overrated Dark Knight, the enjoyably featherweight Mamma Mia, the horrific Midnight Meat Train featuring Lipstick Jungle’s Brooke Shields, the enchanting art house fantasy The Fall, and the daft but tolerable Get Smart).

The Latvian National Opera had not yet reopened for the fall season. Little more could be said in our defense. Having enjoyed another organ concert in the Dome, followed by a Russian meal at Arbat, we once again made our way through the old town to pay a visit to the city’s Forum Cinemas, a multiplex boasting the largest screen in Northern Europe. By the end of our stay, we had pretty much exhausted its late-night offerings (the overrated Dark Knight, the enjoyably featherweight Mamma Mia, the horrific Midnight Meat Train featuring Lipstick Jungle’s Brooke Shields, the enchanting art house fantasy The Fall, and the daft but tolerable Get Smart).