On the eve of the 200th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, I am once again lending an ear to the Great Emancipator. Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have been America’s “radio president”; but in the theater of the mind none among the heads of the States was heard talking more often than Honest Abe. On Friday, 12 February 1937, for instance, at least six nationwide broadcasts were dedicated to Lincoln and his legacy. NBC aired the Radio Guild‘s premiere of a biographical play titled “This Was a Man,” featuring four characters and a “negro chorus.” Heard over the same network was “Lincoln Goes to College,” a recreation of an 1858 debate between Lincoln and Democratic senator Stephen A. Douglas. Try pitching that piece of prime-time drama to network executives nowadays.

Following the Lincoln-Douglas debate was a speech by 1936 presidential candidate Alf Landon, live from the Annual Lincoln Day dinner of the National Republican Club in New York. Meanwhile, CBS was offering talks by Lincoln biographer Ida Tarbell and Glenn Frank, former president of the University of Wisconsin. From Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Illinois, the Gettysburg Address was being recited by a war veteran who was privileged to have heard the original speech back in 1863. Not only live and current, the Whitmanesque wireless also kept listeners alive to the past.

Most closely associated with portrayals of Lincoln on American radio is the voice of Raymond Massey, who thrice took on the role in Cavalcade of America presentations of Carl Sandburg’s Abraham Lincoln: The War Years; but more frequently cast was character actor Frank McGlynn.

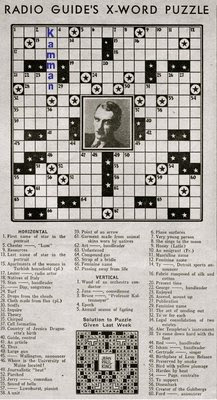

According to the 14 June 1941 issue of Radio Guide, Lincoln “pop[ped] up” in Lux Radio Theater productions “on the average of seven times each year”; and, in order to “keep the martyred President’s voice sounding the same,” producers always assigned McGlynn the part he had inhabited in numerous motion pictures ever since the silent era. In the CBS serial Honest Abe, it was Ray Middleton who addressed the audience with the words: “My name is Abraham Lincoln, usually shortened to just Abe Lincoln.” The program ran for an entire year (1940-41).

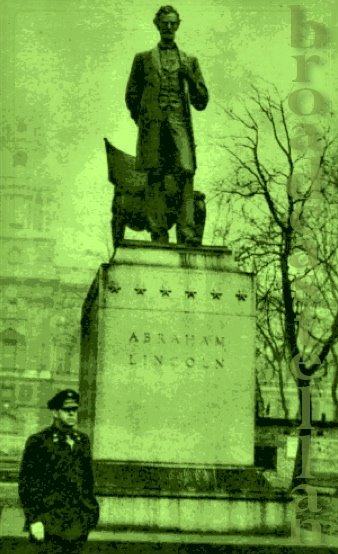

The long and short of it is that, be it in eulogies, musical variety, or drama, Lincoln was given plenty of airtime on national radio, an institution whose personalities paid homage by visiting memorials erected in his honor (like the London one, next to which singer Morton Downey poses above). Nor were the producers of weekly programs whose broadcast dates did not coincide with the anniversary amiss in acknowledging the nation’s debt to the “Captain.” On Sunday, 11 February 1945—celebrated as “Race Relations Sunday”—Canada Lee was heard in a New World A-Coming adaptation of John Washington’s They Knew Lincoln, “They” being the black contemporaries who made an impression on young Abe and influenced his politics. Among them, William de Fleurville.

“Yes,” Lee related,

in Billy’s barbershop, Lincoln learned all about Haiti. And one of the things he did when he got to the White House was to have a bill passed recognizing the independence of Haiti. And he did more than that, too. Lincoln received the first colored ambassador to the United States, the ambassador from the island home of Billy the Barber. And he was accorded all the honors given to any great diplomat in the Capitol of the United States. Yes, the people of Harmony have no doubt that Billy’s friendship with ole Abe had more than a lot to do with it.

Six years later, in 1951, Tallulah Bankhead concluded the frivolities of her weekly Big Show broadcast on NBC with a moving recital of Lincoln’s letter to Mrs. Bixby. That same day, The Eternal Light, which aired on NBC under the auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, presented “The Lincoln Highway.” Drawing on poet-biographer Sandburg’s “complete” works, it created in words and music the “living arterial highway moving across state lines from coast to coast to the murmur ‘Be good to each other, sisters. Don’t fight, brothers.’”

Once, the American networks were an extension of that “Highway,” however scarce the minority voices in what they carried. Four score and seven years ago broadcasting got underway in earnest when one of the oldest stations, WGY, Schenectady, went on the air; but what remains now of the venerable institution of radio is in a serious state of neglect. An expanse of billboards, a field of battles lost, the landscape through which it winds is a vast dust bowl of deregulation uniformity.

Related recording

“They Knew Lincoln,” New World A-Coming (11 Feb. 1945)

Toward the close of this Big Show broadcast, Bankhead recites Lincoln’s letter to Mrs. Bixby (11 Feb. 1951)

“Lincoln Highway,” The Eternal Light (11 February 1951)

My Tallulah salute

Related writings

“Spotting ‘The Mole on Lincoln’s Cheek'”

”Langston Hughes, Destination Freedom, . . .”

A Mind for Biography: Norman Corwin, ‘Ann Rutledge,’ and . . .”

”Carl Sandburg Talks (to) the People”

“The Wannsee Konferenz Maps Out the Final Solution” (on the Eternal Lightproduction of “Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto”)

Listeners tuning in to station WHBI, Newark, New Jersey,

Listeners tuning in to station WHBI, Newark, New Jersey,