No, I don’t mean “N”—even though “N” for Nazis would be a good way to begin any survey of German films produced in the years following the release of Fritz Lang’s classic thriller. The aforementioned Blaue Engel aside, M is perhaps the only German film of the 1930s and ‘40s with which cinéasts the world over can be expected to be familiar. That much more attention is paid to German silent films than to any talking picture produced in Germany before Fassbinder achieved international success is owing, to some degree, to the Teutonic tongue and the aversion Americans have to dubbing and subtitling.

No, I don’t mean “N”—even though “N” for Nazis would be a good way to begin any survey of German films produced in the years following the release of Fritz Lang’s classic thriller. The aforementioned Blaue Engel aside, M is perhaps the only German film of the 1930s and ‘40s with which cinéasts the world over can be expected to be familiar. That much more attention is paid to German silent films than to any talking picture produced in Germany before Fassbinder achieved international success is owing, to some degree, to the Teutonic tongue and the aversion Americans have to dubbing and subtitling.

Another reason for the relative obscurity of classic German cinema is that the US set the standard for commercially viable motion pictures after the silent era came to an end; and few international films could rival the production values to which moviegoers growing up with MGM or Paramount spectacles were accustomed.

Politics, of course, are another key factor. Fassbinder’s 1970s melodramas no doubt appealed to many disenchanted Americans due to their working-class, liberal tendencies, which for an intriguing alternative to the newly emerging, vacuous blockbusters that carried on the tradition of formulaic filmmaking after the production code had been retired in the mid-1960s.

Fassbinder and Werner Herzog aside, what happened between M and Das Boot (1980), the first truly popular German post-World War II film in the US? Or, to narrow it down to the period between the end of the Weimar Republic in 1933 and the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, what kinds of films were produced in Germany when the Reich lost most of its artistic talents to the United States? Over then next few months I am going to look at a number of German movies of that era, beginning with Zu Neuen Ufern (1937) starring the aforementioned Zarah Leander.

Zu Neuen Ufern (meaning “To New Shores”) is a costume drama directed and co-written (or, rather, adapted) by a filmmaker who would become one of Hollywood’s foremost melodramatists: Douglas Sirk (then working under his German name, Detlef Sierck), an artist admired and understood by Fassbinder, who not only emulated Sierck but made him relevant to a 70s audience.

When Zu Neuen Ufern was released in New York—in the German enclave of Yorkville—a New York Times reviewer remarked upon Sierck’s “smooth” direction of a movie full of “highly interesting scenes.” What makes the film most interesting today is not its smoothly plotted series of incidents but its brooding theme of lost liberty and constraint.

The film is set in early Victorian England and New South Wales; one is a prison of conventions, the other a penal colony. Leander’s character, the scandalous yet popular actress Gloria Vane, has taken the blame for a forgery committed by her financially desperate lover, Sir Albert Finsbury, and is sentenced to serve seven years in an Australian penitentiary.

The only way to shorten the sentence is for the prisoners to correct the shortage of women by accepting the marriage proposal of an eligible local. Gloria reluctantly condescends to being wed to an Australian farmer—only to back down and go in search of her lover, who fled to Australia prior to Gloria’s trial and has remained ignorant of her fate.

Having achieved success in the military, Albert is about to marry the governor’s daughter. Gloria, who has learned about the wedding, confesses to Albert that her love for him has been exhausted, upon which the hapless lover commits suicide . . . on the very day of the wedding the thought of which he can no longer endure. Finally recognizing the kindness of the farmer responsible for her release from the prison to which she, in a moment of utter despair, vainly attempts to regain entrance, Gloria marries her liberator.

High melodrama, in short, but admirably underplayed by the remarkably restraint Leander, who does not give her scenes the full treatment for which her compatriot, Garbo, became famous. Its sensational plot notwithstanding, Zu Neuen Ufern is neither cheap nor hysterical. Underscored by Leander’s songs—the haunting “Ich steh’ im Regen” and the sly “Yes, Sir!”—the theme is that of futile longing, of wishing to belong and not being able to exert one’s free will in the pursuit of happiness. It is the nightmare vision of an artist at odds with an increasingly restrictive regime. Sierck was looking for a new “Ufer” and an artistic world beyond UFA, the Nazi-sanctioned studio that produced his films.

To be ”vom anderen Ufer” is a colloquial German term for being beyond traditional marriage, for being set apart if not forcefully transported to the other side for one’s deviance from or defiance of the norm. Neither shore provides a safe harbor. Meanwhile, a common word used in Nazi Germany for aberration in art and nature, “entartet.” is uttered by an unsavory character complaining about the thinness of the female prisoners he has come to inspect in hopes of matrimony.

Sierck seems to adopt the language to pervert the perverse in the society from which the film is only superficially removed. Putting his heroine on display in court, on the stage, and behind bars, he constructs a theater of desire in which a valiant creature like Gloria Vane—who at one point is being pelted with rubbish for singing with feeling after she spots her lost love in the audience—struggles to keep her integrity at the loss of liberty and love.

Douglas Sirk eventually achieved great success on Western shores, yet was forced throughout his career to remain guarded in rendering what could, at best, be an Imitation of Life. In Zu Neuen Ufern, that imitation is the compromise Gloria finds in turning a marriage of convenience into an alternative for solitude, imprisonment, or death.

Now, we happen to have in our collection two of Eric Fraser’s original ink drawings for the “Case of the Jealous Doctor,” an article about the Ruxton case that was published in the 12 November 1949 issue of Leader Magazine. The case itself dates back to 1935. Fraser, as you can see, relished in the sensational character of the murder and the trial, but, unlike the producers of Secrets of Scotland Yard approached his commission with a wry, dark sense of humor.

Now, we happen to have in our collection two of Eric Fraser’s original ink drawings for the “Case of the Jealous Doctor,” an article about the Ruxton case that was published in the 12 November 1949 issue of Leader Magazine. The case itself dates back to 1935. Fraser, as you can see, relished in the sensational character of the murder and the trial, but, unlike the producers of Secrets of Scotland Yard approached his commission with a wry, dark sense of humor.

So, Carole Lombard and Clark Gable got married on this day, 29 March, back in 1939. Ginger Rogers tied the proverbial knot with someone or other in 1929; dear Molly Sugden, whom most folks today know as Mrs. Slocombe, a woman closest to her pussy, was Being Served, be it well or ill, with a license to wed in 1958; and the to me unspeakable ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair proved that he had popped the question fruitfully by walking down the aisle with someone named Cherie. It is a time-honored institution, no doubt; and one that has protected many a woman before her sex was granted the right to vote; but it is concept I find difficult to honor and impossible to obey nonetheless (which explains my love for the first three quarters of the average screwball comedy, the genre in which Lombard excelled).

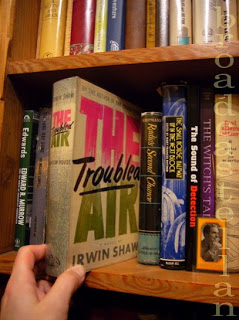

So, Carole Lombard and Clark Gable got married on this day, 29 March, back in 1939. Ginger Rogers tied the proverbial knot with someone or other in 1929; dear Molly Sugden, whom most folks today know as Mrs. Slocombe, a woman closest to her pussy, was Being Served, be it well or ill, with a license to wed in 1958; and the to me unspeakable ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair proved that he had popped the question fruitfully by walking down the aisle with someone named Cherie. It is a time-honored institution, no doubt; and one that has protected many a woman before her sex was granted the right to vote; but it is concept I find difficult to honor and impossible to obey nonetheless (which explains my love for the first three quarters of the average screwball comedy, the genre in which Lombard excelled). This being the birthday of novelist Irwin Shaw (1913-1984), I dusted off my copy of The Troubled Air (1951) to pay tribute to a radio writer who successfully channelled his anger and frustration by feeding it to the press, a rival medium that was only too pleased to get the dirt on broadcasting. Like his

This being the birthday of novelist Irwin Shaw (1913-1984), I dusted off my copy of The Troubled Air (1951) to pay tribute to a radio writer who successfully channelled his anger and frustration by feeding it to the press, a rival medium that was only too pleased to get the dirt on broadcasting. Like his  As usual, I am slow to catch up. A few years ago, the BBC relinquished the rights to televising the Oscars; and since we are not subscribing to the premium channel that does air them, I am relying on the old wireless to transport me to the events. So, here I am listening to …

As usual, I am slow to catch up. A few years ago, the BBC relinquished the rights to televising the Oscars; and since we are not subscribing to the premium channel that does air them, I am relying on the old wireless to transport me to the events. So, here I am listening to …