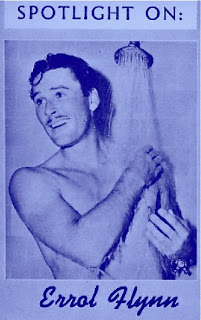

“Oh, I have seen enough and done enough and been places enough and livened my senses enough and dulled my senses enough and probed enough and laughed enough and wept more than most people would suspect.” This line, as long and plodding as a life gone wearisome, was recently uttered by screen legend Olivia de Havilland, now in her 90s. You may well think that, at her age, she had reason enough for saying as much; but Ms. de Havilland was not reminiscing about her own experiences in and beyond Hollywood. She was reciting the words of one of her most virile, dashing, and troubled contemporaries: Errol Flynn, who was born one hundred years ago, on 20 June 1909, and apparently had “enough” of it all before he turned fifty, a milestone he did not live to enjoy.

In her brief talk with BBC Radio 3’s Night Waves host Matthew Sweet, de Havilland talks candidly, yet ever so decorously, about her swash-buckled, devil-may-careworn co-star, about his temperament, his aspirations, his fears. Hers is an aged voice that has a tone of knowing in it. A mellow, benevolent voice that bespeaks understanding. A voice that comforts in its conveyance not of weariness but of awareness, a life well lived and not yet spent.

I could listen for hours to such a voice. I might not care for, learn from or morally improve by hearing what is said—but the timbre gives a meaning to “enough” that the forty-something Flynn never lived to express or have impressed upon him. It is the “enough” of serenity, the “enough” of gratitude, the “enough” of not asking for more and yet not asking less . . . or stop asking at all.

My own life is marked and marred by a certain lack of inquisitiveness, it sometimes strikes me. Being blasé is one of the first masks we don not to let on that we don’t know enough, that we know as much, but don’t know enough simply to ask. I wore such a mask of vainglory when I set out in life, the dullest of lives it seemed to me. My fellow employees had a nickname for me then.

It was my moustache that inspired it. Errol Flynn they called me. Little did they know that, even at age 20, I felt that I had “enough” even though I so keenly felt that I had not had much of anything at all. I simply had enough of not even coming close to the glass of which I might one day have had my fill; but, for three long years, I did not have sense enough to leave that dulling life behind. No voice could talk me out of that barren existence but my own.

It was not easy for me to regain a sense of curiosity; it was as if the pores beneath the mask had been clogged after being concealed so long, my skin no longer alive to the breeze and its promises. I had brushed off more than I dared to absorb. One morning, I took a walk around Central Park with one of Errol Flynn’s leading ladies, Viveca Lindfors, and was neither startled nor thrilled; nor did I not seize the opportunity to inquire about her past or permit her to draw me into her presence as she offered me advice and assistance.

Instead, I preserved the sound of her voice on the tape of my answering machine—like a butterfly beyond the magic of flight—her words saying that she had enough of me was dispensing of my humble services as her dog walker. I am left with canned breath, quite beyond the chance of living what might have been a great story.

Enough of my regrets. I can only hope that, when next I feel that I had “enough,” the word will sound as if it were uttered in what I shall henceforth refer to as a de Havilland sense, with dignity, insight and calm—and an acceptance that is not resignation.

However disheartening California’s majority rule in favor of amending the state constitution so as to protect an institution for which millions of divorced Americans have shown little respect, 5 November 2008 is still a day to inspire confidence in a democracy’s ability to refine and redefine itself, to let go of old prejudices so often upheld as time-honored traditions. To update and appropriate On a Note of Triumph, Norman Corwin’s cautiously optimistic radio play in commemoration of VE Day: “Seems like free men [and women] have done it again!” Perhaps, it seems even more of a victory to those living in Europe and elsewhere around the world.

However disheartening California’s majority rule in favor of amending the state constitution so as to protect an institution for which millions of divorced Americans have shown little respect, 5 November 2008 is still a day to inspire confidence in a democracy’s ability to refine and redefine itself, to let go of old prejudices so often upheld as time-honored traditions. To update and appropriate On a Note of Triumph, Norman Corwin’s cautiously optimistic radio play in commemoration of VE Day: “Seems like free men [and women] have done it again!” Perhaps, it seems even more of a victory to those living in Europe and elsewhere around the world. Having just returned from a trip to Niagara Falls, I was eager to revisit Henry Hathaway’s 1953 technicolor thriller starring Marilyn Monroe. Shrewd, sexy, and sensational, the expertly lensed Niagara is the most brilliantly devised star-making spectacle of Hollywood’s studio era. It has so much going for it that it can afford to be utterly predictable. The Falls are predictable, which does not make them any less exciting. And as much as I enjoy spotting old-time radio performers like the

Having just returned from a trip to Niagara Falls, I was eager to revisit Henry Hathaway’s 1953 technicolor thriller starring Marilyn Monroe. Shrewd, sexy, and sensational, the expertly lensed Niagara is the most brilliantly devised star-making spectacle of Hollywood’s studio era. It has so much going for it that it can afford to be utterly predictable. The Falls are predictable, which does not make them any less exciting. And as much as I enjoy spotting old-time radio performers like the

In written communications, I generally refrain from cursing. I am not sure why so many web journalists feel compelled to express their emotions—even their apparent lack thereof—in terms referring to certain uses of the male sex organ or the issue of our daily excretions. I gather that both spell relief, as does the act of swearing. We all have to get it out of our system once in a while; and I am not one to recommend mealy-mouthing the unsavory by resorting to equivalents of a truculently tossed paper napkin; such disingenuous substitutions have been the curse of radio drama.

In written communications, I generally refrain from cursing. I am not sure why so many web journalists feel compelled to express their emotions—even their apparent lack thereof—in terms referring to certain uses of the male sex organ or the issue of our daily excretions. I gather that both spell relief, as does the act of swearing. We all have to get it out of our system once in a while; and I am not one to recommend mealy-mouthing the unsavory by resorting to equivalents of a truculently tossed paper napkin; such disingenuous substitutions have been the curse of radio drama.  Well, this is St. Nicholas Day. Traditionally, it is the day on which children in Germany (among whom I once numbered) put their hands in their boots to find out whether Saint Nick, passing by overnight, left anything within. Preferably candy, and, given the repository, preferably wrapped. Now, it has been several decades since last I observed the custom. These days, as an every so slightly overweight atheist with somewhat of a passion for boots, I would be more pleased to find my footwear polished.

Well, this is St. Nicholas Day. Traditionally, it is the day on which children in Germany (among whom I once numbered) put their hands in their boots to find out whether Saint Nick, passing by overnight, left anything within. Preferably candy, and, given the repository, preferably wrapped. Now, it has been several decades since last I observed the custom. These days, as an every so slightly overweight atheist with somewhat of a passion for boots, I would be more pleased to find my footwear polished.