The British Broadcasting Corporation has had its share of problems lately, what with its use of licensee fees to indulge celebrity clowns in their juvenile follies. Now, the BBC, which is a non-profit public service broadcaster established by Royal Charter, is coming under attack for what the paying multitudes do not get to see and hear, specifically for its refusal to broadcast a Disasters Emergency Committee appeal for aid to Gaza. According to the BBC, the decision was made to “avoid any risk of compromising public confidence in the BBC’s impartiality in the context of an ongoing news story.” To be sure, if the story were not “ongoing,” the need for financial support could hardly be argued to be quite as pressing.

In its long history, the BBC has often made its facilities available for the making of appeals and thereby assisted in the raising of funds for causes deemed worthy by those who approached the microphone for that purpose. Indeed, BBC radio used to schedule weekly “Good Cause” broadcasts to create or increase public awareness of crises big and small. Listener pledges were duly recorded in the annual BBC Handbook.

From the 1940 edition I glean, for instance, that on this day, 29 January, in 1939, two “scholars” raised the amount of £1,310 for a London orphanage. Later that year, an “unknown cripple” raised £768, while singer-comedienne Gracie Fields’s speech on behalf of the Manchester Royal Infirmary brought in £2,315. The pleas were not all in the name of infants and invalids, either. The Student Movement House generated funds by using BBC microphones, as did the Hedingham Scout Training Scheme.

While money for Gaza remains unraised, the decision not to get involved in the conflict raises questions as to the role of the BBC, its ethics, and its ostensible partiality. Just what constitutes a “worthy” cause? Does the support for the civilian casualties of war signal an endorsement of the government of the nation at war? Is it possible to separate humanitarian aid from politics?

It strikes me that the attempt to staying well out of it is going to influence history as much as it would to make airtime available for an appeal. In other words, the saving of lives need not be hindered by the pledged commitment to report news rather than make it.

Impartiality and service in the public interest were principles to which the US networks were expected to adhere as well, however different their operations were from those of the BBC. In 1941, the FCC prohibited a station or network from speaking “in its own person,” from editorializing, e.g. urging voters to support a particular Presidential candidate; it ruled that “the broadcaster cannot be an advocate”; but this did not mean that airtime, which could be bought to advertise wares and services, could not be purchased as well for the promotion of ideas, ideals, and ideologies.

The broadcasting of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats or his public addresses on behalf of the March of Dimes and the War Loan Drives did not imply the broadcasters’ favoring of the man or the cause.

On this day in 1944, all four major networks allotted time for the special America Salutes the President’s Birthday. Never mind that it was not even FDR’s birthday until a day later. The cause was the fight against infantile paralysis; but that did not prevent Bob Hope from making a few jokes at the expense of the Republicans, who, he quipped, had all “mailed their dimes to President Roosevelt in Washington. It’s the only chance they get to see any change in the White House.”

A little change can bring about big changes; but, as a result of the BBC’s position on “impartiality,” much of that change seems to remain in the pockets of the public it presumes to inform rather than influence.

Related writings

Go Tell Auntie: Listener Complaints Create Drama at BBC

Election Day Special: Could This Hollywood Heavy Push You to the Polls?

“Our guest stars might well have been tailored for the celebrated parts of Peter and Ellie,” host Orson Welles remarked as he raised the curtain on the Campbell Playhouse production of “It Happened One Night,” heard on this day, 28 January, in 1940. Quite a bold bit of barking, that. After all, the pants once worn by bare-chested Clark Gable were handed down to William Powell, who was debonair rather than brawny. “Mr. William Powell surely needs no alteration at all,” Welles insisted, even though the material required considerable trimming. Meanwhile, the part of Ellie, the “spoiled and spirited heiress” whom Peter cuts down to size until he suits her, was inherited by Miriam Hopkins. It had “certainly never been more faultlessly imagined than tonight,” Welles declared. Indeed, as I was

“Our guest stars might well have been tailored for the celebrated parts of Peter and Ellie,” host Orson Welles remarked as he raised the curtain on the Campbell Playhouse production of “It Happened One Night,” heard on this day, 28 January, in 1940. Quite a bold bit of barking, that. After all, the pants once worn by bare-chested Clark Gable were handed down to William Powell, who was debonair rather than brawny. “Mr. William Powell surely needs no alteration at all,” Welles insisted, even though the material required considerable trimming. Meanwhile, the part of Ellie, the “spoiled and spirited heiress” whom Peter cuts down to size until he suits her, was inherited by Miriam Hopkins. It had “certainly never been more faultlessly imagined than tonight,” Welles declared. Indeed, as I was  I enjoy spending time by myself. It’s a good thing I do, considering that I am pretty much on my own in my enthusiasm for old and largely obscure radio programs, especially those that I only get to hear about. Listening, like reading, is a solitary experience; to share your thoughts about what went on in your head can be as difficult and frustrating as it is to put into words the visions and voices of a dream. Besides, unless you are talking to somebody who gets paid to listen, your dreams and reveries are rarely as stimulating to others as they are to yourself. This isn’t exactly a dream, much less one come true—but it’s a jolly good facsimile thereof.

I enjoy spending time by myself. It’s a good thing I do, considering that I am pretty much on my own in my enthusiasm for old and largely obscure radio programs, especially those that I only get to hear about. Listening, like reading, is a solitary experience; to share your thoughts about what went on in your head can be as difficult and frustrating as it is to put into words the visions and voices of a dream. Besides, unless you are talking to somebody who gets paid to listen, your dreams and reveries are rarely as stimulating to others as they are to yourself. This isn’t exactly a dream, much less one come true—but it’s a jolly good facsimile thereof.

I’ve had quite a few “silent nights” here at broadcastellan lately (to use an old broadcasting term); and yet, I have been preparing all along for the weeks and months to come, those dark and cheerless days of mid-winter when keeping up with the out-of-date can be a real comfort. Not that the conditions here in our cottage have been altogether favorable to such pursuits, given that we had to deal with a number of blackouts and five days without heating oil, during which the “room temperature” (a phrase stricken from my active vocabulary henceforth) dropped below 40F. Not even a swig of brandy to warm me. I have given up swigging for whatever duration I deem fit after imbibing rather too copiously during

I’ve had quite a few “silent nights” here at broadcastellan lately (to use an old broadcasting term); and yet, I have been preparing all along for the weeks and months to come, those dark and cheerless days of mid-winter when keeping up with the out-of-date can be a real comfort. Not that the conditions here in our cottage have been altogether favorable to such pursuits, given that we had to deal with a number of blackouts and five days without heating oil, during which the “room temperature” (a phrase stricken from my active vocabulary henceforth) dropped below 40F. Not even a swig of brandy to warm me. I have given up swigging for whatever duration I deem fit after imbibing rather too copiously during

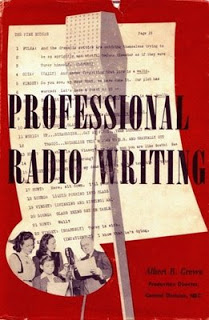

“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day,

“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day,