Fancy that, Florence Farley! You were one lucky teenager, when, early in March 1939, a photographer from the ever enterprising Hearst paper New York Journal American came to see a fashion show planned by you and the kids in your neighborhood—the none too fashionable Tenth Avenue in Manhattan. Subsequently, you were chosen to go to Hollywood and become a “Lady for a Day.” What’s more, on this day, 1 May, you got to tell millions of Americans about your experience, dutifully marvelling at the “simply swell” Lux toilet soap in return. After all, you were talking to Cecil B. DeMille, nominal producer of the Lux Radio Theater, and there had to be something in it for those who made you over, young lady, and made your day.

Fancy that, Florence Farley! You were one lucky teenager, when, early in March 1939, a photographer from the ever enterprising Hearst paper New York Journal American came to see a fashion show planned by you and the kids in your neighborhood—the none too fashionable Tenth Avenue in Manhattan. Subsequently, you were chosen to go to Hollywood and become a “Lady for a Day.” What’s more, on this day, 1 May, you got to tell millions of Americans about your experience, dutifully marvelling at the “simply swell” Lux toilet soap in return. After all, you were talking to Cecil B. DeMille, nominal producer of the Lux Radio Theater, and there had to be something in it for those who made you over, young lady, and made your day.

Mr. DeMille was in New York City for the premiere of his Union Pacific, while Leslie Howard took over as narrator and host in Hollywood; so, C. B. didn’t really have to go out of his way (or send you back, all expenses paid, to Tinseltown) to meet up with you. You had returned by then from your West Coast adventure, the title of “Lady” being bestowed upon you “with the understanding” that you would return to your “own workaday world.”

“I was just another girl,” you told the famous director, just as the script had it. “Gee,” you exclaimed, as anyone should, having had a break like yours. When prompted to do so, you told listeners of going to your “first nightclub,” where you met Dorothy Lamour and “danced with Franchot Tone.” He probably felt like dancing, too, considering that he was single again, his marriage with Joan Crawford having recently ended in divorce, which might not be as bad as going back to the tenements. By the way, I’m watching Harriet Craig tonight and wonder what it must have been like, living with Crawford. But never mind that now.

While in Hollywood, you also got to make a screentest, go for a “bicycle ride with Bob Hope,” and appear in a Paramount picture. Not that I could find your name anywhere on the Internet Movie Database. Who knows just how much of your dream come true is true, Florence Farley. Tell me, were you really glad to return to the tenements to live with your grandma and go out with boys who only dream of being Errol Flynn? Did you get to keep those “Cinderella slippers,” never having “paid more than $2 for shoes” before?

Yours was another thin slice of Hollywood baloney, a West Coast diversion from the butchery about to commence in the east to the east of you. It’s no coincidence, either, that the Lux Radio Theater presented an adaptation of Damon Runyon’s ”Madame La Gimp” (later aired under original title on the Damon Runyon Theater program and remade as Pocketful of Miracles starring Glenn Ford, who would have celebrated his 91st birthday today, had he not died last August). Nor is it surprising that your fairy tale fits so well into the scheme of selling things, of carving the mess of life into neat bars of soap.

You know, Flo, listening to your voice (more real than the hooey you were asked to repeat) and wondering about the life behind those lines of yours—the life behind the “human interest” story and the publicity act you were that spring—sure beats following the sentimental play on offer that night. Now let’s wash our hands of the whole affair, without so much as thinking about lathering with the sponsor’s product . . .

“Well, gentlemen, let’s get aboard,” says the pilot in Norman Corwin’s “They Fly Through the Air.” What a “peach” of a morning. “You couldn’t ask for a better day” . . . to blow up a few hundred civilians. The verse play (

“Well, gentlemen, let’s get aboard,” says the pilot in Norman Corwin’s “They Fly Through the Air.” What a “peach” of a morning. “You couldn’t ask for a better day” . . . to blow up a few hundred civilians. The verse play ( Being that this is the anniversary of the birth of Guglielmo Marconi, a scientist widely, however mistakenly, regarded as the inventor of the wireless, I am once again lending an ear to the medium with whose plays and personalities this journal was meant to be chiefly concerned. Not that I ever abandoned the subject of audio drama or so-called old-time radio; but efforts to reflect more closely my life and experiences at home or abroad have induced me of late to turn a prominent role into what amounts at times to little more than mere cameos. Besides, “Writing for the Ear” is a course I am offering this fall at the local university; so I had better prick ’em up (my auditory organs, I mean) and come at last to that certain one of my senses.

Being that this is the anniversary of the birth of Guglielmo Marconi, a scientist widely, however mistakenly, regarded as the inventor of the wireless, I am once again lending an ear to the medium with whose plays and personalities this journal was meant to be chiefly concerned. Not that I ever abandoned the subject of audio drama or so-called old-time radio; but efforts to reflect more closely my life and experiences at home or abroad have induced me of late to turn a prominent role into what amounts at times to little more than mere cameos. Besides, “Writing for the Ear” is a course I am offering this fall at the local university; so I had better prick ’em up (my auditory organs, I mean) and come at last to that certain one of my senses. No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is

No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is

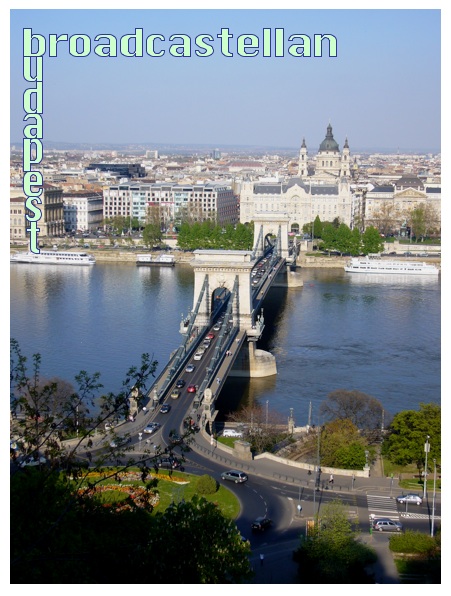

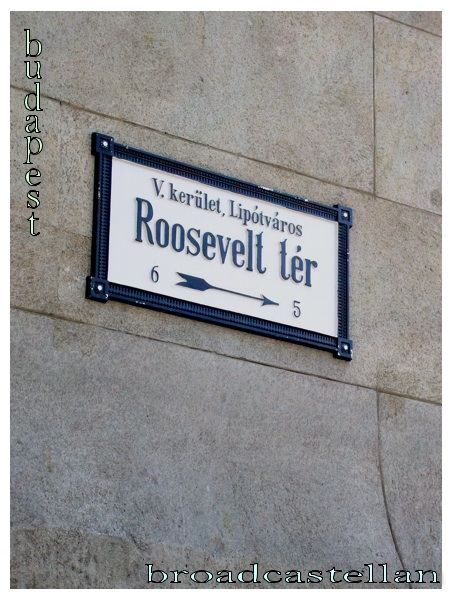

Well, this is it. My last entry into the broadcastellan journal before I’m off to Budapest, from which spot I hope to be reporting back on 12 April with a snapshot of Roosevelt Square, in commemoration of FDR’s death in 1945. Supposedly, our hotel room has wireless access; so I might not have to share my impressions retrospectively (as I have done on almost every previous occasion, after trips to London and Madrid, Istanbul and Scotland, Cornwall and New York City). This time, perhaps, I won’t have to catch up with myself as well as our pop cultural past.

Well, this is it. My last entry into the broadcastellan journal before I’m off to Budapest, from which spot I hope to be reporting back on 12 April with a snapshot of Roosevelt Square, in commemoration of FDR’s death in 1945. Supposedly, our hotel room has wireless access; so I might not have to share my impressions retrospectively (as I have done on almost every previous occasion, after trips to London and Madrid, Istanbul and Scotland, Cornwall and New York City). This time, perhaps, I won’t have to catch up with myself as well as our pop cultural past.

Okay, so, I tend to overdramatize. I can’t help it. I was born with a hyperbole on my lips. Turns out, I am still a man of the world wide web, despite the scheduled (and currently ongoing) landline repairs I lamented previously. At least, the prospect of not having access to the internet motivated us to realize some last-minute holiday plans by booking a trip to . . . Budapest. However eager I might be to share my experience, the challenge, as always, is not to drift too far from the format and subject of this journal and yet to make it reflect my everyday life, whether I am spending An Evening with Queen Victoria (as I will be on 22 April) or going back to my old neighborhood in New York City (on 14 May). Still, it is going to be (almost) all about Budapest from now until my royal visit.

Okay, so, I tend to overdramatize. I can’t help it. I was born with a hyperbole on my lips. Turns out, I am still a man of the world wide web, despite the scheduled (and currently ongoing) landline repairs I lamented previously. At least, the prospect of not having access to the internet motivated us to realize some last-minute holiday plans by booking a trip to . . . Budapest. However eager I might be to share my experience, the challenge, as always, is not to drift too far from the format and subject of this journal and yet to make it reflect my everyday life, whether I am spending An Evening with Queen Victoria (as I will be on 22 April) or going back to my old neighborhood in New York City (on 14 May). Still, it is going to be (almost) all about Budapest from now until my royal visit.