Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

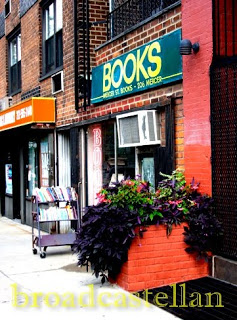

Gone were the days when a teenager like Mary Jones, whose story I encountered on a trip to the Welsh town of Bala last weekend, walked twenty-five miles, barefooted, for the privilege of owning a Bible. Sure, I enjoy the occasional daytrip to Hay-on-Wye, the renowned “Town of Books” near the English border where, earlier this month, I snatched up a copy of the BBC’s 1952 Year Book (pictured). Still, ever since the time of the great Victorian novelists, the reading public has been walking no further than the local lending library or wherever periodicals were sold to catch up on the latest fictions and follow the exploits of heroines like Becky Sharp in monthly installments.

In Victorian times, the demand for stories was so great that poorly paid writers were expected to churn them out with ever greater rapidity, which left those associated with the literary trade to ponder new ways of meeting the supply. In Gissing’s New Grub Street (1891), a young woman assisting her scholarly papa is startled by an

advertisement in the newspaper, headed “Literary Machine”; had it then been invented at last, some automaton to [. . .] turn out books and articles? Alas! The machine was only one for holding volumes conveniently, that the work of literary manufacture might be physically lightened. But surely before long some Edison would make the true automaton; the problem must be comparatively such a simple one. Only to throw in a given number of old books, and have them reduced, blended, modernised into a single one for today’s consumption.

Barbara Cartland notwithstanding, such a “true automaton” has not yet hit the market; but the recycling of old stories for a modern audience had already become a veritable industry by the beginning of the second quarter of the 20th century, during which “golden age” the wireless served as both home theater and ersatz library for the entertainment and distraction craving multitudes.

A medium of—and only potentially for—modernity, radio has always culled much of its material from the past, “Return with us now” being one of the phrases most associated with aural storytelling. It is a phenomenon that led me to write my doctoral study Etherized Victorians, in which I relate the demise of American radio dramatics to the failure to establish or encourage its own, autochthonous, that is, strictly aural life form.

Sure, the works of Victorian authors are in the public domain; as such, they are cheap, plentiful, and, which is convenient as well, fairly innocuous. And yet, for reasons other than economics, they strike us as radiogenic. Like the train whistle of the horse-drawn carriage, they seem to be the very stuff of radio—a medium that was quaint and antiquated from the onset, when television was announced as being “just around the corner.”

Perhaps, the followers of Becky Sharp should not toss out their books yet; as American radio playwright Robert Lewis Shayon pointed out, the business of adaptation is fraught with “artistic problems and dangers.” He argued that he “would rather be briefed on a novel’s outline, told something about its untransferable qualities, and have one scene accurately and fully done than be given a fast, ragged, frustrating whirl down plot-skeleton alley.”

It was precisely for this circumscribed path, though, that American handbooks like James Whipple’s How to Write for Radio (1938) or Josephina Niggli’s Pointers on Radio Writing (1946) prepared prospective adapters, reminding them that, for the sake of action, they needed to “retain just sufficient characters and situations to present the skeleton plot” and that they could not “afford to waste even thirty seconds on beautiful descriptive passages.”

As I pointed out in Etherized, broadcast writers were advised to “free [themselves] first from the enchantment of the author’s style” and to “outline the action from memory.” Illustrating the technique, Niggli reduced Jane Eyre—one of the most frequently radio-readied narratives—to a number of plot points, “bald statements” designed to “eliminate the non-essential.” Only the dialogue of the original text was to be restored whenever possible, although here, too, paraphrases were generally required to clarify action or to shorten scenes. Indeed, as Waldo Abbot’s Handbook of Broadcasting (1941) recommended, dialogue had to be “invented to take care of essential description.”

To this day, radio dramatics in Britain, where non-visual broadcasting has remained a viable means of telling stories, the BBC relies on 19th-century classics to fill much of its schedule. The detective stories of Conan Doyle aside, BBC Radio 7 has just presented adaptations of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847-48), featuring the aforementioned Ms. Sharp, and currently reruns Trollope’s Barchester Chronicles (1855-67). The skeletons are rather more complete, though, as both novels were radio-dramatized in twenty installments, and, in the case of Trollope’s six-novel series, in hour-long parts.

BBC Radio 4, meanwhile, has recently aired serializations of Trollope’s Orley Farm (1862), Wilkie Collins’s Armadale (1866) and Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1862). Next week, it is presenting both Charlotte Brontë’s Villette and Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth (both 1853), the former in ten fifteen minute chapters, the latter in three hour-long parts.

Radio playwright True Boardman once complained that adaptations for the aural medium bear as close a relation to the original as “powdered milk does to the stuff that comes out of cows.” They are culture reconstituted. “[R]educed, blended, [and] modernised“, they don’t get a chance to curdle . . .

Note: Etherised Victorians was itself ‘reduced and blended,’ and published as Immaterial Culture in 2013.

Related writings (on Victorian literature, culture and their recycling)

“Hattie Tatty Coram Girl: A Casting Note on the BBC’s Little Dorrit”

“Valentine Vox Pop; or, Revisiting the Un-Classics”

“Curtains Up and ‘Down the Wires'”

“Eyrebrushing: The BBC’s Dull New Copy of Charlotte Brontë’s Bold Portrait”

A long time (well, okay, make that ‘about four and a half years’) ago I came to the realization that the key to keeping an online journal—and one’s fingers regularly on the keyboard in its service—is serialization: some kind of evolving plot that, like life and Stella Dallas on a diet, keeps thickening and thinning from Monday till Doomsday until the inevitable sundown that not even Guiding Light could outshine.

A long time (well, okay, make that ‘about four and a half years’) ago I came to the realization that the key to keeping an online journal—and one’s fingers regularly on the keyboard in its service—is serialization: some kind of evolving plot that, like life and Stella Dallas on a diet, keeps thickening and thinning from Monday till Doomsday until the inevitable sundown that not even Guiding Light could outshine.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.