I was among those tuning in live today to catch the announcement of the Academy Award nominations. It was a surprising moment of up-to-date enthusiasm, considering that I have only seen one of the films competing in the major categories (and that being the less-than-timely Mrs. Henderson Presents). Not exactly riveted to the spot after Mira Sorvino had stepped to the podium, I promptly consulted the Internet Movie Database (which also posted my latest review today) to find out whether Ms. Sorvino’s career is now reduced to reading a list of now-factor names from a teleprompter.

I was among those tuning in live today to catch the announcement of the Academy Award nominations. It was a surprising moment of up-to-date enthusiasm, considering that I have only seen one of the films competing in the major categories (and that being the less-than-timely Mrs. Henderson Presents). Not exactly riveted to the spot after Mira Sorvino had stepped to the podium, I promptly consulted the Internet Movie Database (which also posted my latest review today) to find out whether Ms. Sorvino’s career is now reduced to reading a list of now-factor names from a teleprompter.

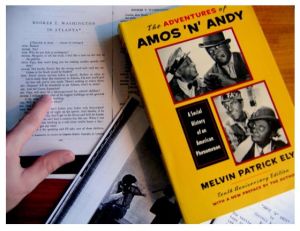

I stood corrected (if not entirely convinced of her A-list status), then sat down, caught a glimpse of a butterfly in the garden (in January?), and wandered off again into the generally shrugged-off-as-irrelevant realm of old-time radio. Fellow radio scholar Howard Blue, who wrote an informative book on radio propaganda and left a comment on broadcastellan earlier today, will probably not be among those shrugging.

Unlike in the allegedly relevant motion pictures of today, America’s wartime activities featured prominently on radio, whether in serious drama, juvenile adventures, or on comedy programs. On this day, 31 January, in 1943, radio comedian Fred Allen joked about the power of broadcasting in wartime. For instance, the Russian advance slowed down on account of “some mix-up” through which the “Russians army got four days ahead of [radio news commentator] H. V. Kaltenborn.”

The quiz show Truth or Consequences, Allen quipped, could solve the nation’s debt problem. A contestant on that program had just received thousands of pennies in the mail, sent in by empathetic listeners sorry that she answered a question incorrectly. Now, if only Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau could appear on that show and give the wrong answers! Also discussed was a ruling by the OPA (Office of Price Administration) that dining out constituted an “uplift for morale” and was thus exempt from rationing.

And then there was that other Oscar announcement, made by Oscar Levant (pictured above, in one of my humble attempts at illustration). The noted American composer appeared on Allen’s show that day to declare that he was all washed-up. Levant, who was also a panelist on the celebrity quiz program Information, Please!, complained that his reputation was ruined after he had performed at Carnegie Hall alongside Allen’s archrival, the notoriously dreadful violinist Jack Benny.

“We mustn’t go to itsy-bitsy pieces,” Allen tried to calm the discomposed musician. “You sound like an old kindergarten teacher I once I killed in Syracuse.” So, what kind of jobs were available for an over-the-hill composer and ex-radio celebrity? Leafing through the want ads, Allen finds demand for “steamfitters, plumbers, sandhogs, stevedores.” “You’ve got the wrong column,” Levant sneers, “That’s for women!”

Eventually, Allen suggests that Levant turn radio jingles into symphonies and “clean up” with the sponsors. It’s a living. Sure beats having to read a roster of your honored peers—unless you are too deluded to realize that you are no longer among them.

Going to the pictures is fast disappearing on the public lists of favorite pastimes; so, congratulating yourself on your own supposed relevance—rather than honoring potentially enduring cinematic excellence—is a desperate attempt at concealing your impending obsolescence. Forever keeping up with the out-of-date, I, for one, will never have to stoop to such measures.

Well, before I make an appointment with The Phantom President, another one of the lesser known motion pictures starring my favorite actress, Ms. Claudette Colbert, I am going to listen again to a radio adaptation of a story that was initially considered as a vehicle for Colbert, but fell into the lap of lucky Bette Davis instead. I am referring of course to “The Wisdom of Eve,” a dramatization of which was broadcast on this day, 24 January, in 1949—thus nearly two years prior to the general US release of the celebrated movie version known as All About Eve.

Well, before I make an appointment with The Phantom President, another one of the lesser known motion pictures starring my favorite actress, Ms. Claudette Colbert, I am going to listen again to a radio adaptation of a story that was initially considered as a vehicle for Colbert, but fell into the lap of lucky Bette Davis instead. I am referring of course to “The Wisdom of Eve,” a dramatization of which was broadcast on this day, 24 January, in 1949—thus nearly two years prior to the general US release of the celebrated movie version known as All About Eve. Well, my

Well, my

Only a few days ago I commemorated my 100th entry into the broadcastellan journal by going in search of fellow old-time radio bloggers. Not a week later, the subject has become considerably more prominent among bloggers with an entire classroom of neophytes posting their thoughts on radio’s “imagined community” and reviewing individual programs selected by their instructor. It remains to be seen whether the thought-sharing extends beyond the virtual college annex, or just how long the on-air engagement with “yesterday’s internet” (as Gerald Nachman called the radio) will last. “Tired of the everyday routine? Ever dream of a life of romantic adventure? Want to get away from it all?” Just hop over to technorati and

Only a few days ago I commemorated my 100th entry into the broadcastellan journal by going in search of fellow old-time radio bloggers. Not a week later, the subject has become considerably more prominent among bloggers with an entire classroom of neophytes posting their thoughts on radio’s “imagined community” and reviewing individual programs selected by their instructor. It remains to be seen whether the thought-sharing extends beyond the virtual college annex, or just how long the on-air engagement with “yesterday’s internet” (as Gerald Nachman called the radio) will last. “Tired of the everyday routine? Ever dream of a life of romantic adventure? Want to get away from it all?” Just hop over to technorati and

After yesterday’s intriguing ghost story on Suspense, I went in search for a few more seasonal treats from the same series. Unfortunately, listening to the sentimental offerings that aired on this day, 21 December, in 1950 and 1953, respectively, is about as thrilling as finding yet another pair of socks under the tree.

After yesterday’s intriguing ghost story on Suspense, I went in search for a few more seasonal treats from the same series. Unfortunately, listening to the sentimental offerings that aired on this day, 21 December, in 1950 and 1953, respectively, is about as thrilling as finding yet another pair of socks under the tree.