“Life is very long.” That’s the opening line of August: Osage County, which isn’t exactly short, either. Nor is it short on family crisis, on anxiety, guilt, anger . . . and laughs. Pulitzer Prize or not, it’s honest-to-goodness melodrama, homemade (which is best). No wonder it is roping in the crowds. The British, too. Even those who’d expect a play set in Oklahoma to feature dancing cowboys and a rousing rendition of “Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’” I’m one of those folks; and I still went. Couldn’t have had a better ride if I’d been in the surrey with the fringe on top, neither. On account of that nasty eye infection, I missed out on catching the ride on Broadway; but I sure was glad to catch up with it here, with most of the original cast in the house. And what a house!

“Life is very long.” That’s the opening line of August: Osage County, which isn’t exactly short, either. Nor is it short on family crisis, on anxiety, guilt, anger . . . and laughs. Pulitzer Prize or not, it’s honest-to-goodness melodrama, homemade (which is best). No wonder it is roping in the crowds. The British, too. Even those who’d expect a play set in Oklahoma to feature dancing cowboys and a rousing rendition of “Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’” I’m one of those folks; and I still went. Couldn’t have had a better ride if I’d been in the surrey with the fringe on top, neither. On account of that nasty eye infection, I missed out on catching the ride on Broadway; but I sure was glad to catch up with it here, with most of the original cast in the house. And what a house!

Not the Lyttleton Theatre, which is just fine; the Weston’s house, I mean, which is somewhere out there in Pawhuska, Oklahoma. Inside, it’s hotter than a blazing summer afternoon on a tin roof, with or without the cat. But crazy old Violet Weston ain’t one for pussyfooting around. Her husband, Bev, is the one who sets us up with that opening line; he’s saying it to the new help he’s hired to take care of Vi (“She’s the Indian who lives in my attic,” Vi later tells the assembled family). To care for her, and that old dark house, is “getting in the of [his] drinking.” Or so he says.

Bev’s a former literature teacher and an even more former poet. That’s why he’s quoting T. S. Eliot, “who bothered to write [that line] down.” I was a little worried about that line. I thought, if he is going on quoting people, I might want to look things up. And who’d stop the play for me! Or try to remember that one name or line or word and then get lose the plot. It’s not a modernist drama, fortunately; and we soon come to realize why Bev’s saying it, and what it means. For Bev, “very long” means too long. He’s had enough of life, of life with Vi, whose mouth is so foul she’s got mouth cancer, and whose mood can be even fouler, no matter how many of those over-prescribed pills she swallows (“Try to get ‘em away from me and I’ll eat you alive”).

Well, Bev is not exactly dry, either; but he’s sober enough to plan and make his exit. Soon after making arrangements with the new help he’s taking himself out of the family picture . . . which is when the fun begins. There’s Vi’s tacky sister Mattie Fae (“Feel it. Sweat is just dripping down my back”); her husband, Charlie (“I don’t want to feel your back”); their bumbling, “complicated” son (“Honey, you have to be smart to be complicated,” Mattie Fae disagrees); Vi and Bev’s three middle-aged daughters, a pot-smoking fourteen-year-old granddaughter (“Look at her boobs,” Mattie Fae exclaims—and she is not the only one taking notice, as one of Vi’s daughters finds out when her fiancé starts “goofin’” with her; and then there’s Vi’s louse of a son-in-law, who likes them younger as well (“You’re a good, decent, funny, wonderful woman, and I love you,” the louse tells his soon-to-be ex-wife, “but you’re a pain in the ass”). Just wait until they all sit down for dinner.

If this sounds like last Thanksgiving to you, you might be squirming in your seat; but, for the rest of us, it comes as a relief to witness a family even more dysfunctional than our own. You couldn’t possibly cram more melodrama into a single play without making it, say, Polyester. But that would be Baltimore.

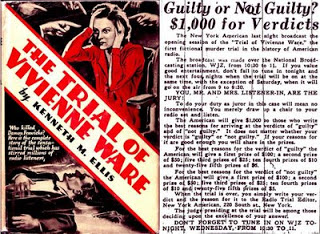

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,