Well, I did say “romancing,” didn’t I? It may have sounded more like “pooping on” in the entry I balderdashed off yesterday. The accompanying image, by the way, referred to the new television series Balderdash and Piffle (on BBC2 in the UK), which invites the public to challenge, edit and amend the Oxford English Dictionary. More about that in a few days, perhaps. So, why “romancing”?

Well, I did say “romancing,” didn’t I? It may have sounded more like “pooping on” in the entry I balderdashed off yesterday. The accompanying image, by the way, referred to the new television series Balderdash and Piffle (on BBC2 in the UK), which invites the public to challenge, edit and amend the Oxford English Dictionary. More about that in a few days, perhaps. So, why “romancing”?

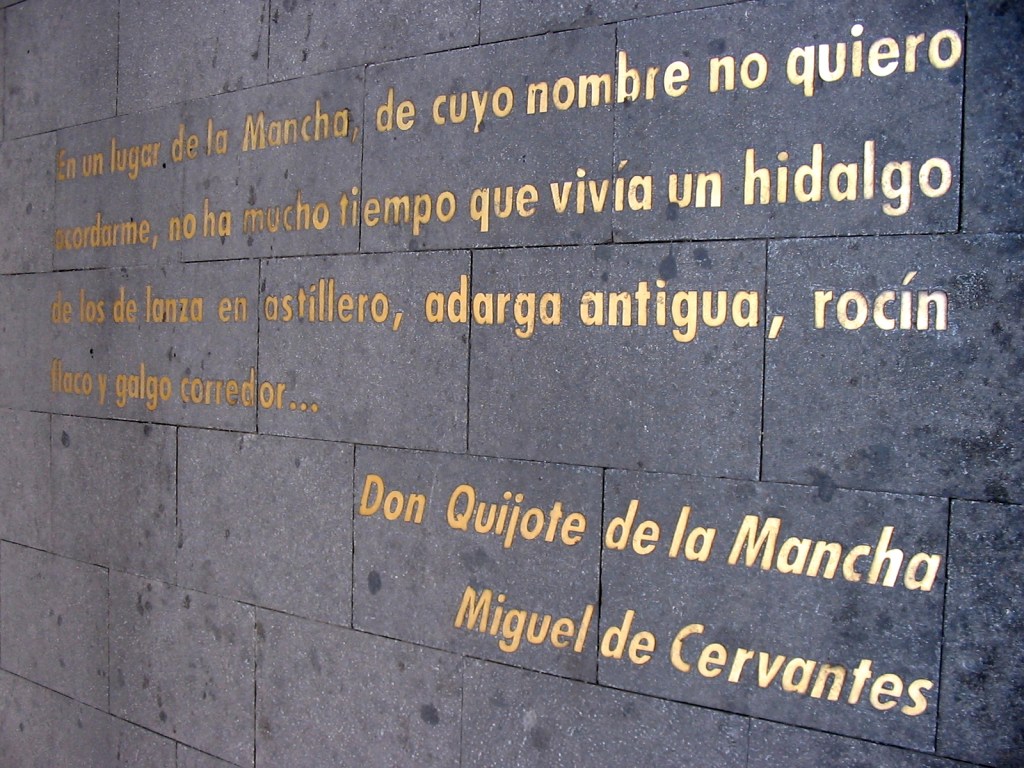

For one thing, I am very much attracted to and fascinated by remakes and adaptations. I am not one of those clamoring for so-called original material in favor of a smart revision or charming homage. Let’s face it: “originality” is a downright prelapsarian concept. There are only so many juicy stories to tell. We should not expect to be handed another forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge; which does not mean that we should settle for any old lemon.

Reworking a so-called classic can be a questioning of its definitiveness, its very status. It can also mean a translation of a great idea or worthwhile thought into a context and language more accessible to present-day audiences, thus a way of keeping the original alive in spirit, rather than slaughtering it.

As diverting as both King Kong and The Producers might have been, I feel they have failed on both accounts. Yet even though I am not infrequently disappointed with remakes and sequels (which are often remakes in disguise), I seek them out again and again, embracing them—in concept, at least—as an alternative form of criticism.

Last night, for instance, I watched The Saint in London (1939), which aired during the first week of January 2006 on BBC 2 in a series of four Saint adventures. The movie is a reworking of Leslie Charteris’s mystery “The Million Pound Day.” So, I could not refrain from digging up that story from my library and will probably report my comparison in the near future, drawing on the 1940s Saint radio series as well.

I felt compelled to do the same after watching King Kong, of which I found an undated radio adaptation, with Captain Englehorn as narrator. And I might take the same multimedia approach to the Charlie Chan mystery, The Black Camel, having recently come across a first edition of the 1933 omnibus The Celebrated Cases of Charlie Chan at a local second-hand bookstore.

Tracing an adaptation to its source—not necessarily an original itself—often enhances my appreciation or understanding of a work and its workings. It does not follow that the older version is superior by virtue of its antecedents, even though our fondness for it may make us sceptical of any attempts at revision.

While in London, I saw two 1930s plays. One was the Kaufman and Hart comedy Once in a Lifetime, the other And Then There Were None. The latter is based on the 1939 Agatha Christie novel in which ten strangers find themselves on a remote island, murdered, one by one, by an unknown adversary among them. Rene Clair’s 1945 film adaptation is a marvel of both atmosphere and fidelity—right until the very end. One reviewer having his say on the internet movie database (IMDb) remarks that the novel’s ending “would never *ever* work in a dramatized setting, film or stage”—but Kevin Elyot’s new stage adaptation proved him wrong. I couldn’t wait for the play to be over. Not because it was so awful, not because I wanted to know the identity of the murderer (familiar to me from book and film)—but because I needed to see what was being done to the ending. A very satisfying counting down of corpses it turned out to be.

Once in a Lifetime—staged by the National Theatre, no less—was dead on arrival. Even the spirit of nostalgia, if I were possessed by it, could not assist in animating this propped up carcass. Period costumes, smart sets, and fidelity to the script—itself much in need of tightening and deserving of fresher jokes—are no substitute for a director’s knowing and assured handling of material that was still relevant and topical in 1930 (the advent of cinema’s sound era), but that now comes across as a quaint and pointless revisitation of Singin’ in the Rain—without the Singin’. A soggy muddle indeed.

The program for the show supplied a “Once in a Lifetime Glossary” to an audience confronted with a slew of 75-year-old in-jokes. What’s left is a dim farce of decidedly low wattage. Very few directors can work up and sustain the energy to prevent the potentially zany from being plain dull.

In short, rummaging through remakes and revivals can be a disenchanting exercise; but there are rewards in romancing the reproducers, especially if they take you to the occasional gem you might have otherwise overlooked.

Well, it seems that complimentary wireless internet access is not yet a standard feature of the average London hotel room. Jury’s Inn, Islington, for instance, charges £10 per day for a broadband connection. That’s about 20 to 25 percent of the cost for a room, and as such no piffling add-on to your bill. So I felt compelled to take a prolonged but not unwelcome break from blogging, taking the small fortune thus saved to the theater box office, the movies, and the temples of high art. Meanwhile, my lingering cold (the New York acquisition mentioned

Well, it seems that complimentary wireless internet access is not yet a standard feature of the average London hotel room. Jury’s Inn, Islington, for instance, charges £10 per day for a broadband connection. That’s about 20 to 25 percent of the cost for a room, and as such no piffling add-on to your bill. So I felt compelled to take a prolonged but not unwelcome break from blogging, taking the small fortune thus saved to the theater box office, the movies, and the temples of high art. Meanwhile, my lingering cold (the New York acquisition mentioned  Yesterday, we took the train up and across the border to Birmingham, England, to see the exhibition Love Revealed: Simeon Solomon and the Pre-Raphaelites at the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. Deceptively saccharine, the title of this show (borrowed from Solomon’s fanciful dream narrative “A Vision of Love Revealed by Sleep”) also refers to the Victorian artist’s troubled life, to the disclosure of his secret and the end it meant for his career as a commercially viable painter.

Yesterday, we took the train up and across the border to Birmingham, England, to see the exhibition Love Revealed: Simeon Solomon and the Pre-Raphaelites at the Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery. Deceptively saccharine, the title of this show (borrowed from Solomon’s fanciful dream narrative “A Vision of Love Revealed by Sleep”) also refers to the Victorian artist’s troubled life, to the disclosure of his secret and the end it meant for his career as a commercially viable painter. Well, I am on my way to London in a few hours, even though I have barely recovered from my trip to New York City, a souvenir of which is a lingering cold. Still, I am looking forward to a weekend in the metropolis, where I’ll be reunited with my best pal to celebrate his birthday and the twentieth anniversary of our friendship. We used to have our annual get-togethers in the Big Apple, but the Big Smoke will do.

Well, I am on my way to London in a few hours, even though I have barely recovered from my trip to New York City, a souvenir of which is a lingering cold. Still, I am looking forward to a weekend in the metropolis, where I’ll be reunited with my best pal to celebrate his birthday and the twentieth anniversary of our friendship. We used to have our annual get-togethers in the Big Apple, but the Big Smoke will do. Feeling as miserable as I do right now (the aforementioned cold), I was tempted to abandon the “On This Day” feature and escape the self-imposed strictures of such a format. Then I came across a recording of Words at War that made me decide not to disenthrall myself just yet. I might not have gotten to know Jean Helion, had it not been for the frustrating and inept adaptation of his wartime memoir They Shall Not Have Me, first broadcast on 23 September 1943.

Feeling as miserable as I do right now (the aforementioned cold), I was tempted to abandon the “On This Day” feature and escape the self-imposed strictures of such a format. Then I came across a recording of Words at War that made me decide not to disenthrall myself just yet. I might not have gotten to know Jean Helion, had it not been for the frustrating and inept adaptation of his wartime memoir They Shall Not Have Me, first broadcast on 23 September 1943.

Moving to the UK from the movie junkie heaven that is New York City meant having to find new ways of getting my cinematic fix. Gone are the nights of pre-code delights at the

Moving to the UK from the movie junkie heaven that is New York City meant having to find new ways of getting my cinematic fix. Gone are the nights of pre-code delights at the