“Glory be to God for dappled things,” Gerard Manley Hopkins famously exclaimed—in a poem, no less, that was first published some three decades after his death. The delayed recognition he received makes us now think of Hopkins as a modern poet rather than a Victorian one. Brought to light in the darkest of days, his words spoke to an inglorious post-World War world so different from the perfectly imperfect one he knew that he could hardly have anticipated it. And yet, anticipate us he did—and “[a]ll things counter, original, spare, strange.” Secure in his belief in the One “whose beauty is past change,” Hopkins could revel in all that is “fickle, freckled (who knows how?),” in a life that is protean, fleeting and undone—the ever unfinished and often dirty business of living reconciled to our longing for perfection, permanence, and the eternal.

“Glory,” I wanted to shout, for dusty things, for art so long that no one in a single lifespan can ever be done with it—and for a chance to dust off works neglected and ignored to bring them to life anew. Not because they are perfect, not because they are classic or timeless—but because, in all their sketchiness, patchiness and almost-but-not-quiteness, they remind us—and glorify—the long and short of life: the clouds on the horizon, the waves hitting the rocks, the light of the ever setting sun on ancient mountains.

I was too busy tackling the dust (and keeping my mouth shut not to take it in) to wax philosophical and shout then—but I do think and feel it now when I look at some of the smaller canvases of Christopher Williams (1873-1934), a once well known artist, and native of Wales, whose forgotten and, in many cases, never before exhibited works I had a small part in putting back on public display here at the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth.

Far more than Williams’s monumental paintings of momentous historical, mythological, and biblical themes, which belong to an age fast fading in his day, what is glorious to me are his studies of sea, sky, and rock—of the mutable majesty, the perennial transience of nature that he sought to encapsulate while working against time: the dying light of day, the waves against unwavering cliffs, the clash of the evanescent with the apparently everlasting.

A few years ago, when I knew little of Wales and less of Williams, I visited one of the spots along the coast he had painted and compared what I saw to what he had depicted. The rocks were the same all right, but the sea and the sky looked nothing like the painting. Had he painted what he wanted to see, wanted us to see, or remembered seeing? Years later, when I returned to the same scene, the sea was turquoise, the sky cerulean—it was as Williams had pictured it. Only then did I appreciate the long hours he must have spent studying the light and the colors it creates. What was before him was fleeting—what is before us is unfinished—but what his quick brush transported one hundred years into his future is the product of a study far from cursory. Perhaps it takes a knowledge of the presence of something past change to see past the unchanging and glory in the changeable.

And there they are now, on view for a short while (until 22 September 2012), these past glimpses of change, these small studies alongside his finished—staid, staged and stately—compositions I helped to ready for the big show. Not that the project is done and dusted, as, together with my partner, Robert Meyrick, the curator of the present retrospective, I shall be co-authoring a book on the artist’s life and work . . .

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous. “. . . and visited the Sea.” I have not read the poetic works of Emily Dickinson in many a post-collegiate moon; yet, as wayward as my memory may be, I never forgot those glorious opening lines. You might say that is has long been an ambition of mine to utter them, to experience for myself the magic they evoke; but, until recently, I have failed on three accounts to follow Emily in her excursion. That is, I had no dog to take along; nor did I never live close enough to the sea to approach it on foot, at least not with the certain ease that might induce me to undertake such a venture.

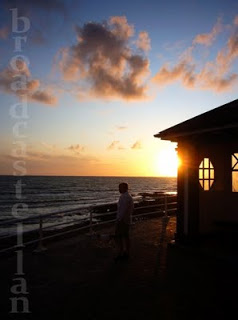

“. . . and visited the Sea.” I have not read the poetic works of Emily Dickinson in many a post-collegiate moon; yet, as wayward as my memory may be, I never forgot those glorious opening lines. You might say that is has long been an ambition of mine to utter them, to experience for myself the magic they evoke; but, until recently, I have failed on three accounts to follow Emily in her excursion. That is, I had no dog to take along; nor did I never live close enough to the sea to approach it on foot, at least not with the certain ease that might induce me to undertake such a venture. Besides, as Victorian storyteller Cuthbert Bede once remarked, it is “well worth going to Aberystwith [. . .] if only to see the sun set.” So, I’m starting late instead and take my dog for evening visits to the sea. No “Mermaids” have yet come out of the “basement” to greet me; nor any of those bottlenose dolphins that are on just about every brochure or poster designed to boost the town’s tourist industry. They are out there, to be sure; but unlike Ms. Dickinson, I’m not taking the plunge to get up close and let my “Shoes [ . . .] overflow with Pearl” until the rising tide “ma[kes] as He would eat me up.”

Besides, as Victorian storyteller Cuthbert Bede once remarked, it is “well worth going to Aberystwith [. . .] if only to see the sun set.” So, I’m starting late instead and take my dog for evening visits to the sea. No “Mermaids” have yet come out of the “basement” to greet me; nor any of those bottlenose dolphins that are on just about every brochure or poster designed to boost the town’s tourist industry. They are out there, to be sure; but unlike Ms. Dickinson, I’m not taking the plunge to get up close and let my “Shoes [ . . .] overflow with Pearl” until the rising tide “ma[kes] as He would eat me up.” On this sunless Tuesday morning, though, I started just early enough to keep Montague’s appointment with the veterinarian. No walk along the promenade for the old chap, to whom the change of schedule was no cause for suspicion. Now, I don’t know what possessed me to agree to his being anesthetized to have his teeth cleaned, other than Montague’s stubborn refusal to permit us to brush them. I trust that, once he has forgiven me for this betrayal of his trust, that we have many more late starts to meet and mate with the sea . . .

On this sunless Tuesday morning, though, I started just early enough to keep Montague’s appointment with the veterinarian. No walk along the promenade for the old chap, to whom the change of schedule was no cause for suspicion. Now, I don’t know what possessed me to agree to his being anesthetized to have his teeth cleaned, other than Montague’s stubborn refusal to permit us to brush them. I trust that, once he has forgiven me for this betrayal of his trust, that we have many more late starts to meet and mate with the sea . . . I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities.

I rose before the sun, and ran on deck to catch an early glimpse of the strange land we were nearing; and as I peered eagerly, not through mist and haze, but straight into the clear, bright, many-tinted ether, there came the first faint, tremulous blush of dawn, behind her rosy veil [ . . .]. A vision of comfort and gladness, that tropical March morning, genial as a July dawn in my own less ardent clime; but the memory of two round, tender arms, and two little dimpled hands, that so lately had made themselves loving fetters round my neck, in the vain hope of holding mamma fast, blinded my outlook; and as, with a nervous tremor and a rude jerk, we came to anchor there, so with a shock and a tremor I came to my hard realities. “So, here he is. My father. In a churchyard in the furthest tip of Llŷn. Eighty years old. Wild hair blowing in the wind. Overcoat that could belong to a tramp. Face like something hewn out of stone, staring into the distance.” The man observing is Gwydion, the middle-aged son of R. S. Thomas (1913-2000)—“Poet. Priest. Birdwatcher. Scourge of the English. The Ogre of Wales.” With this terse description opens Neil McKay’s “Alone Together,” a radio play first aired last Sunday on BBC Radio 3 (

“So, here he is. My father. In a churchyard in the furthest tip of Llŷn. Eighty years old. Wild hair blowing in the wind. Overcoat that could belong to a tramp. Face like something hewn out of stone, staring into the distance.” The man observing is Gwydion, the middle-aged son of R. S. Thomas (1913-2000)—“Poet. Priest. Birdwatcher. Scourge of the English. The Ogre of Wales.” With this terse description opens Neil McKay’s “Alone Together,” a radio play first aired last Sunday on BBC Radio 3 (

Having spent a week traveling through Wales and the north of England—up a castle, down a gold mine, and over to Port Sunlight, where Lux has its origins—I finally got to sit down again to take in an old-fashioned show. That show was My Fair Lady, a production of which opened last night at the

Having spent a week traveling through Wales and the north of England—up a castle, down a gold mine, and over to Port Sunlight, where Lux has its origins—I finally got to sit down again to take in an old-fashioned show. That show was My Fair Lady, a production of which opened last night at the