All right, so I’m sounding like an aging burlesque queen about to toss her tassels and turn in the G-string that is a turn-on no longer—but, by Gypsy, I am tired of stripping. Wallpaper, I mean. This old Mazeppa has nothing but a scraper for a gimmick, and the only hand she ever got for all her grinding is a mighty sore one. I just could not live with it, though, that dreadful pattern—having it stare me down in defiance, berate me for letting myself be defeated by all the work that needs doing in the old house we plan on inhabiting before long. The idea (not mine, mind) was to paint over it—but I scratched that faster than I could scrape. It might peep out from behind the paint, that ghastly design. It might start to creep up on me if I don’t get at it first—just like in that most famous of all interior decorating nightmares, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “Yellow Wallpaper” (1892). To date, Gilman’s feminist tale of terror is the most convincing argument for taking it all off.

To the tormented soul telling the story, the paper she finds in her room—the room in which she is meant to rest—becomes a “constant irritant.” Within a few short weeks of studying it, for want of the intellectual activity denied to her, she is driven to the distraction once classified as hysteria:

The color is hideous enough, and unreliable enough, and infuriating enough, but the pattern is torturing.

You think you have mastered it, but just as you get well underway in following, it turns a back-somersault and there you are. It slaps you in the face, knocks you down, and tramples upon you. It is like a bad dream.

Unlike the blank, “dead” paper on which she writes in secret, the wallpaper is teeming with life, just below the surface. It is the surface of conventions that Gilman tears down with a vengeance:

This bed will not move!

I tried to lift and push it until I was lame, and then I got so angry I bit off a little piece at one corner—but it hurt my teeth.

Then I peeled off all the paper I could reach standing on the floor. It sticks horribly and the pattern just enjoys it! All those strangled heads and bulbous eyes and waddling fungus growths just shriek with derision!

When Gilman’s story was adapted for US radio, listeners to CBS’s Suspense program may have felt rather differently about this schizophrenic battle when, in a broadcast that aired on 29 July 1948, it was enacted by Agnes Moorehead, who, in tackling the part, had to struggle as well with our memories of the neurotic and disagreeable Mrs. Elbert Stevenson, her most famous Suspense role. “Sorry, Wrong Paper,” I kept thinking as I witnessed the disintegration. And yet, as the hard and cutting echoes of Mrs. Stevenson suggest, paper can beat both rock and scissors—a thought that filled me with renewed terror.

“It dwells in my mind so!” Gilman’s character remarks, tellingly, about the dreaded wall covering. The dwelling has overmastered the dweller, like a wild animal resisting domestication, a beast beyond paper training. The prospect of being dominated or possessed in this way by a questionable décor is a scenario horrifying enough for me to put penknife to paper . . . and keep stripping.

Yes, it’s been a good day. Yes, sir, a good day. Started out that way. When I woke up, the warm, friendly smell of breakfast was drifting upstairs, and the blossoms of my cherry tree were tapping against the windows. Mmm. Lying there, I felt seventeen. Until Marilly’s voice bolted upstairs . . .

Yes, it’s been a good day. Yes, sir, a good day. Started out that way. When I woke up, the warm, friendly smell of breakfast was drifting upstairs, and the blossoms of my cherry tree were tapping against the windows. Mmm. Lying there, I felt seventeen. Until Marilly’s voice bolted upstairs . . .  Well, this is St. Nicholas Day. Traditionally, it is the day on which children in Germany (among whom I once numbered) put their hands in their boots to find out whether Saint Nick, passing by overnight, left anything within. Preferably candy, and, given the repository, preferably wrapped. Now, it has been several decades since last I observed the custom. These days, as an every so slightly overweight atheist with somewhat of a passion for boots, I would be more pleased to find my footwear polished.

Well, this is St. Nicholas Day. Traditionally, it is the day on which children in Germany (among whom I once numbered) put their hands in their boots to find out whether Saint Nick, passing by overnight, left anything within. Preferably candy, and, given the repository, preferably wrapped. Now, it has been several decades since last I observed the custom. These days, as an every so slightly overweight atheist with somewhat of a passion for boots, I would be more pleased to find my footwear polished. I guess we have all been exposed to them, no matter how quickly our fingers move to stop our ears. Sounds that drive us up the wall and get us to scream, shiver, and wince. For some, it is the screeching of a piece of chalk on a blackboard (perhaps already one of the “endangered” sounds aforementioned; for others it might be a creaking door swinging on rusty hinges. Fiddlesticks (however annoying they might be), that’s nothing compared to the noise Agnes Moorehead has to endure in the Suspense thriller “The Thirteenth Sound,” first broadcast on this day, 13 February, in 1947.

I guess we have all been exposed to them, no matter how quickly our fingers move to stop our ears. Sounds that drive us up the wall and get us to scream, shiver, and wince. For some, it is the screeching of a piece of chalk on a blackboard (perhaps already one of the “endangered” sounds aforementioned; for others it might be a creaking door swinging on rusty hinges. Fiddlesticks (however annoying they might be), that’s nothing compared to the noise Agnes Moorehead has to endure in the Suspense thriller “The Thirteenth Sound,” first broadcast on this day, 13 February, in 1947. The afternoon couldn’t be any less gloomy. The sky is of a deep blue, the air is fresh, and—until the health hazard that is Tony Blair gets his death wish to turn the West of Britain

The afternoon couldn’t be any less gloomy. The sky is of a deep blue, the air is fresh, and—until the health hazard that is Tony Blair gets his death wish to turn the West of Britain

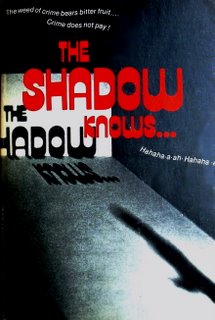

I remember the first time I heard the menacing voice of The Shadow—and it was not over the radio. I was a college student in New York City and was cleaning the Upper East Side apartment of a fading southern belle. Well, I needed the cash and she was too much of

I remember the first time I heard the menacing voice of The Shadow—and it was not over the radio. I was a college student in New York City and was cleaning the Upper East Side apartment of a fading southern belle. Well, I needed the cash and she was too much of